A look behind KU’s fall enrollment numbers

The headlines about KU’s fall enrollment sounded much like a Minnesotan’s assessment of winter: It could be worse.

Indeed it could have been, given the uncertainties brought on by the coronavirus and rumblings among students that they might sit out the year if their courses were online.

Depending on how you measure, enrollment on the Lawrence and Edwards campuses fell either 2.7% (headcount) or 3.4% (full-time equivalency) this fall. That is about the same as the nationwide average (-3%) but slightly worse than the average decline of 1.4% at four-year public universities, according to data from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

A single year’s top-level data provides only a limited view of a much bigger picture. To better understand this year’s enrollment, we need to take a broader and deeper look in terms of geography, history and demographics. Here’s what I’m seeing in data from Academics and Analytical Research, the Kansas Board of Regents and some other sources.

Enrollment declines throughout the state

KU was hardly alone in dealing with the sting of an enrollment decline. Among regents universities, Pittsburg State had the largest decline in enrollment (-5.9%), followed by K-State (-5.1%), KU, Wichita State (-3.1%), Fort Hays State (-2.8%) and Emporia State (-2.3%).

As a whole, the state’s community colleges fared far worse, with a combined drop of 11.7%, about 2 percentage points higher than the national average. Johnson County Community College had the largest decline (18.7%). Enrollment at JCCC has fallen 23.5% over the past five years, a troubling statistic given KU’s proximity and institutional connections to JCCC. During that same period, enrollment at the state’s 19 community colleges has fallen by an average of 18.6%, according to regents statistics. Eight of those colleges recorded declines of more than 20%.

Kansas is one of 11 states where the decline in undergraduate enrollment exceeded the national average, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, Others include Missouri, Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana and Florida. Only five states recorded increases in undergraduate enrollment, including Nebraska.

Putting the trends into perspective

Over the past 50 years, college and university enrollment has reflected broader societal trends that made a college degree a sought-after goal. As numbers trend downward, though, enrollment figures also highlight the looming challenges that most of higher education faces.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, undergraduate enrollment rose steadily as baby boomers entered college in larger percentages than previous generations. The number of colleges – especially community colleges – grew, providing more opportunities for students to seek a degree. Federal aid, including low-interest loans, also expanded, as the federal government promoted the importance of education and invested in university research. A college degree became the minimum standard for many jobs and led to higher salaries over a degree holder’s lifetime.

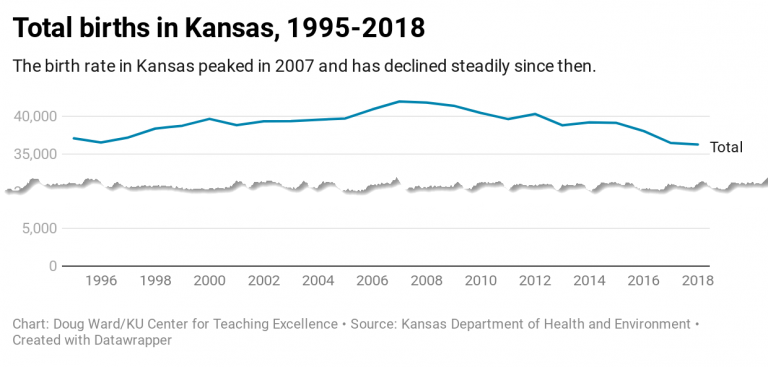

Those trends are certainly reflected in KU’s enrollment data. Between 1965 and 1991, headcount enrollment at KU nearly doubled. (See the chart below.) It declined after a recession in the early 1990s, but rose again in the early 2000s, peaking in 2008 during the recession. It declined until 2012, stabilized briefly, and then began another decline, one that is very likely to continue given a declining school population. K-12 enrollment in Kansas peaked in the 2014-15 school year, according to Kansas State Board of Education data. It is projected to start a significant decline in the late 2020s, largely because of a decline in birth rates after the recession of 2007-08. Since peaking in 2007, birth rates in Kansas have fallen 13.6%. (See the chart above with the most recent data available from the state.)

In another disturbing trend, the number of Kansas students coming to KU has dropped 17.7% since 2011. (It was down 2.9% this year.) The university has attracted more out-of-state students, who make up about 40% of the student population, but the trends among Kansas students are bleak.

KU attracts the largest number of students from Johnson County, which accounts for 28.3% of the university’s enrollment. The number of students from Johnson County has fallen 7.3% over the past decade. That is far less than the drop in students from other counties from which the university draws the most students: Douglas (-25.2% since 2011), Sedgwick (-27.1%), Shawnee (-26%). Declines in others aren’t as dramatic but are still troubling: Wyandotte (-9.8%), Leavenworth (-3.3%) and Miami (-3.2%). Others are far worse: Saline (-30.5%), Riley (45.1%), Reno (42.3%).

More Hispanic students, fewer international students

One of the most interesting developments I saw in enrollment this fall was that for the first time in decades, the number of Hispanic students at KU exceeded the number of international students. (See the chart below.)

This reflects two major trends. First the Hispanic population of Kansas has grown more than 70% since 2000. Hispanics now make up more than 12% of the Kansas population and 18.5% of the U.S. population. The number of Hispanic students at KU rose 3.3% this year and has risen nearly every year since the mid-1980s.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration has taken a less-than-welcoming stance toward international students and immigration in general. That, combined with a global pandemic and lack of a coherent plan for combatting the pandemic, has sent international enrollment at U.S. universities plummeting. By one estimate, the number of new international students at U.S. universities could soon reach the lowest level since World War II.

As KU reported, the number of international students at the university declined more than 18% this fall. That decline is greater than the 12.5% decline in international students at public four-year universities, according to data from the National Student Clearinghouse.

Other trends worth noting

- A continuing rise in female students. The number of female students on the Lawrence campus continued to exceed the number of male students. The number of male students fell 1.4% this year, compared with 0.5% for female students, and has fallen 11% since 2011. For the first time in at least a decade, the number of women who transferred to KU was larger than the number of men who transferred. Men now make up 47.5% of the KU student population. Nationally, the number of women seeking college degrees surpassed the number of men seeking degrees in 1979. That was the first time since World War II that more women than men attended college, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. In the 40 years since then, the gap has only increased, as it did again this year. Sixty-seven KU students did not identify as male or female this year. That was similar to the 73 in 2018 but down from 509 in 2019, suggesting that last year’s spike was intended as statement against the reporting system, primarily by graduate students.

- Another decline in graduate enrollment. The number of graduate students on the Lawrence campus fell 2.2% this year, compared with an increase of 4.7% at public four-year universities. That is the fourth consecutive year of declines. The number of graduate students has fallen 12.5% since 2011. Graduate enrollment at KU peaked in 1991 and has declined 25% since then. (See the chart labeled University of Kansas Enrollment, 1965-2020.)

- Another increase in part-time enrollment. I noted last year that the number of part-time students had been rising steadily. That number rose 6.8% again this year and is 18.9% higher than it was in 2011. Part-time students now account for 17.7% of the student body. That isn’t necessarily bad, given the university’s agreement to provide dual enrollment classes with the Lawrence Public School District. It is concerning, though, given that more students nationally are choosing to pursue their degrees part time. That gives them more flexibility to work but delays graduation. In what I see as a related trend, the number of non-degree-seeking students, although still small at 445, has increased more than 200% since 2011.

- Some perspective on freshman enrollment. As the university reported, the number of incoming freshmen declined 7.2% this fall. Since a peak in 2016, the number of incoming freshmen has declined by 9.5%. Even so, the total this year is 7% above that of 2011.

- A continuing drop in transfer students. The transfer rate to KU can only be described as glum. The number of new transfers to the Lawrence and Edwards campuses was down 8.2% this year and the total fell below 1,000 students for this first time in more than a decade. The number of transfer students has fallen 32.7% since 2011, following the downward trend in community college enrollment.

- Large growth from a few states. Since 2011, the number of students from seven states has increased by an average of 45%: Missouri (+40%), Illinois (+46%), Colorado (+47%), Nebraska (+76%), California (+33%), Oklahoma (+61%), Wisconsin (+42%). Collectively, students from those states (by headcount) make up 22% of the student body at the Lawrence and Edwards campuses. KU also attracts a considerable number of students from Texas and Minnesota, although those numbers have grown only slightly over the past 10 years.

- Business continues to grow. Even as overall university enrollment declined, undergraduate enrollment in the School of Business rose 7.9% this year and has grown 131% since 2011. Enrollment in engineering declined 2.2% this year but is up 31.6% since 2011. Enrollment in liberal arts and sciences continues to sag. Undergraduate enrollment in the College fell 4.8% this year and is down 21% since 2011. Graduate enrollment was down only slightly less. Even so, the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences still has nearly five times as many students as either business or engineering.

Where do we go from here?

Demographically over the past decade, the KU student population has become more Hispanic, more multiethnic and more female but less Kansan and less international. It is still predominantly white (68%) and is more oriented toward business and engineering. It has grown younger over the past decade, with students 22 and younger making up about 70% of the student body, compared with about 64% in 2011.

The university has about 1,500 fewer students than it did a decade ago. It has a slightly larger percentage of undergraduate students than at the start of the decade, although the proportion of undergraduates to graduate students has remained within a small range since 2000. Even so, graduate enrollment has fallen more than 14% since 2011.

I’ve written frequently about the challenges higher education faces, about the need to understand our students better, to innovate, to emphasize the human element of teaching and learning, to think about what we are preparing our students to do, and to provide a clearer sense of what higher education provides. This year’s enrollment figures simply reinforce all of that.

This is the fourth consecutive year of enrollment decline at KU and the ninth consecutive decline at the six regents universities. Those declines have become increasingly painful because of growing reliance on tuition and fees to pay the bills. In Fiscal 2019, tuition and fees accounted for more than 30% of the Lawrence campus’s $900 million in revenue. State appropriations accounted for just over 15%. In other words, students pay about $2 for every $1 the state provides. That is unlikely to improve in the foreseeable future, especially with the state facing a projected $1.5 billion shortfall in the current fiscal year.

In other words, the future of the university depends greatly on enrollment. Enrollment depends greatly on the value that students and parents see in KU. It’s up to all of us to make sure they do indeed understand that value.

We interrupt your malaise with this message from Abraham Lincoln

Dear sleep deprived colleagues,

We ask you to take a few minutes to consider these not-so-solemn words. Full disclosure: You have all been muted for the duration of this speech.

Four score and 700 years ago (or so it seems), the coronavirus brought forth on this campus a new semester, conceived in haste, cloaked in masks, and dedicated to the proposition that all Zoom meetings suck the life from us equally.

Now we are engaged in a great civil chore, testing whether this faculty and these students, or any faculty and students so distanced and so sapped of energy and so deprived of even a hint of a break, can long endure. We are met within a great white tent that reminds us every day of that chore. We have come to dedicate a portion of that tent as a final resting place for the remnants of normalcy we have all surrendered, six feet apart and clutching personal squeeze bottles of hand sanitizer, in so that this university might live.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate – we cannot commiserate with – we cannot even take a nap within – this tent. The brave instructors and students, mildly coherent or fully brain-dead, who struggled here, have already commiserated far above our poor power to whine or snap. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but it can never forget that this semester was, without doubt, the longest and most challenging in … in … like forever, for crying out loud.

It is for us, the mildly conscious and highly caffeinated martyrs of alternating cohorts, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work that seems fated never to be nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us – coasting 500 miles, uphill, on a single wheel, to the end of the semester – that from these husks of human beings all around us we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave their last full measure of self-respect – that we here highly resolve that these brain-dead shall not have burned out in vain – that this university, upon a hill, shall birth a new never-ending semester – and that education of the remote, by the remote, for the remote, shall not perish from the earth.

You may unmute yourself now.

Now take a deep breath (and a nap if you need one). You can make it through the rest of the semester. — Doug Ward

P.S. Don’t forget to visit the Center for Teaching Excellence’s Flexible Teaching Guide for ideas and inspiration.

40 days (and 40 nights?) of teaching in confinement: A diary

The shift to remote teaching this semester quickly became a form of torture by isolation inflicted upon us by microscopic organisms. There has to be a bright spot somewhere, though. Right?

13 days until isolation. A carefully planned list of 1,368 VERY IMPORTANT THINGS to do during spring break dissolves before my eyes as I am enlisted to help create a website on remote teaching. In a university conference room, a dozen people stare at laptop computers. Half-a-dozen others peer out like the Brady Bunch from a videoconference screen running Zoom. I fear this is a premonition.

10 days until isolation. I ponder the enormity of the task before us. All university classes will shift to a remote format. Thousands of people will hook up their brains to an electronic network, abandon a corporeal existence, and struggle to make sense of a new reality. Wait. I’ve seen that movie.

Two days until isolation. At my last physical meeting on campus, I glance at my feet and realize I am wearing two different kinds of boots. A colleague snickers. Then everyone snickers. “We’re not really laughing at you,” she says. “It’s just …” I try to look at the bright side. At least I put my boots on the right feet.

One day until isolation. I spend an hour digging through drawers and cabinets for anything I might need for working at home. I leave the office with a backpack strapped to my back, three large bags dangling from my hands and a whiteboard tucked beneath my arm. I can’t shake the feeling that I have forgotten something. My phone! Six feet behind me, the office door slams shut.

Isolation Day 1. A fog settled over Lawrence during the night. A perfect setting for the first day of remote classes. A bright spot: Candy Crush announces unlimited lives all week long.

Isolation Day 2. Laptop in lap, I sit in my living room and join a Zoom meeting. On screen, a colleague lounges on a tropical beach at an undisclosed location. Oh, wait. That’s a fake background. He probably just did that to get attention. I roll my eyes.

Isolation Day 3. I scour the web for a picture of the Tardis, the police call box that the Doctor uses to traverse time and space in Doctor Who. During a time of social isolation, economic turmoil and general uncertainty, I can go anywhere and any time. Such symbolism! I set the image of the Tardis as my background in Zoom.

Isolation Day 4. “You’ll have to tell us what that background is,” a colleague says at the beginning of a Zoom meeting. Inside, part of me dies.

Isolation Day 5. I change my Zoom background to the bridge of the Starship Enterprise.

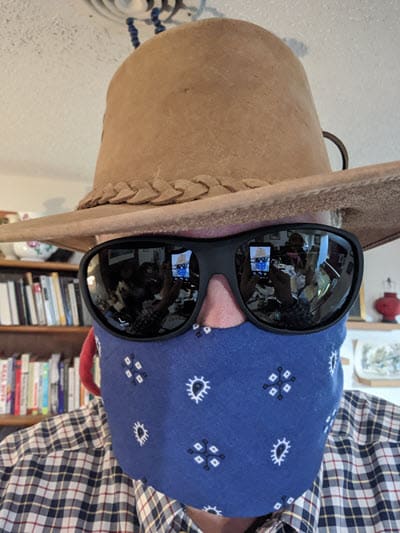

Isolation Day 6. I need to get groceries. I fashion a mask from a blue bandana. Then I put pull my leather outback hat down low. I giggle. I tell my wife I look like I’m getting ready to rob a stagecoach. My wife rolls her eyes. I shrug and change to a red ballcap. At the grocery store, everyone stays back well more than six feet.

Isolation Day 7. My personal care appointments fall like dominos. My dental appointment, canceled. My eye appointment, canceled. My haircut, canceled. I consider whether my out-of-control hair will eventually cover my toothless mouth. I decide it won’t matter because I won’t be able to see.

Isolation Day 8. Growing weary of working in the living room, I excavate a corner of my sons’ former bedroom for a workspace. It feels strangely familiar. A bed next to me is heaped with books, cast-off clothes, pillows, blankets, a laundry basket filled with hangers and some boxes filled with – is that a muskrat hide? I feel like I have taken refuge in a dorm room. Or is it my office?

Isolation Day 9. I gleefully plug in a smart speaker in the excavated spare bedroom I have turned into a work area. My wife unplugged the speaker in the main part of the house months ago because she thought I was always talking to myself. Now, with the door closed, I can ask it anything. Anything! I think long and hard. “Hey, Cortana. What’s the weather?” Like I really need to know.

Isolation Day 10. I set up the portable whiteboard I retrieved from my office and scrawl a list of VERY IMPORTANT THINGS in green marker. Then I brace for ultra-productivity. I envision a self-help book about VERY IMPORTANT THINGS and a tour as a motivational speaker. “How do you do it?” people will ask. I will simply hold up a green marker and say … Oh, no. Does it really say PERMANENT?

Isolation Day 11. After six hours of Zoom meetings, my laptop has fused to my lap, my headset has fused to my ears, my eyeballs hang limp, and I feel as if I have traveled into another dimension. I change my Zoom background to a glacier lagoon from Iceland and head to the refrigerator for a beer. A puddle has appeared in front of the refrigerator. Either it needs to be defrosted or it has developed incontinence. Note to self: Ask Cortana.

Isolation Day 12. As I venture outside, I find that the 5-year-old girl next door has created a Fairy Garden in her front lawn. I know because she has planted a sign. I take a picture, add images of fairies and send it to her mom. The message I get back: Mom likes it, but the 5-year-old wants me to know that the fairies in my picture don’t look real. I am unable to work for the rest of the day.

Isolation Day 13. Students mention feeling disconnected from their classes. I feel disconnected from the students. So I set up office hours on Zoom. No one shows up. Note to self: Remote teaching is exactly like in-person teaching.

Isolation Day 14. A green arrow appears on the sidewalk on our block. It points south. I sense symbolism.

Isolation Day 15. I walk to the end of the driveway and retrieve the morning newspaper. It’s still dark. The streets are quiet. The moon glows against patchy clouds. Birds chatter. Trees rustle. Tulips are blooming. So are the redbuds. Well, I got in a nature walk today.

Isolation Day 16. TikTok shows video after video of cats and dogs jumping over rolls of toilet paper that their owners have stacked in doorways. I am not making this up. One cat hurdles what must be at least 40 rolls of toilet paper. I look in our bathroom cabinet. Three rolls. I stack them in the doorway and hop over them. Then I put them back before my wife asks me whether I have lost my mind.

Isolation Day 17. I have worn nothing but slippers for six days. Why do I feel guilty?

Isolation Day 18. I’m afraid people will get the wrong idea. I didn’t literally mean that I wear nothing but slippers. I meant that I wear nothing but slippers on my feet. On my feet! I’m sure that’s right. If I were wrong, someone on Zoom would have told me. Wouldn’t they?

Isolation Day 19. I reach the ignominious total of 50 hours on Zoom since isolation began. I wiggle my toes in celebration.

Isolation Day 20. In an apparent act of defiance, a plastic bolt that holds down one side of the toilet seat snaps and flies into the wall. I stare. I shake my head. Then I put the lid down gently. I can’t deal with this right now.

Isolation Day 21. I have ignored my online to-do list for 18 straight days. Three feet away, the green list of VERY IMPORTANT THINGS on the whiteboard seems to animate into an evil grin. Or maybe it’s my imagination. I’m never sure anymore.

Isolation Day 22. In a webinar: Flatten the curve. In email: Flatten the curve. In the newspaper: Flatten the curve. On the radio: Flatten the curve. In my dreams: Flatten the curve. For posterity: My brain has already flattened.

Isolation Day 23. No matter how much grading I do, the amount of unread student work seems to grow. So does the strain on my back. I lapse into a daydream about Sherpas, loaded down with gear, guiding hikers on a treacherous mountain trail. I shiver and blink. What was I doing? I can’t remember. I shut down my computer.

Isolation Day 24. During a webinar, the chancellor says that more than 90% of KU employees are now working remotely. He says this while wearing a suit and tie. Does he really a suit and tie while he works from home? I’ve worn the same shirt for four days. I have absolutely no interest in wearing a tie.

Isolation Day 25. The whiteboard on which I wrote VERY IMPORTANT THINGS torments me. Somehow, none of those things are getting done, even though I used green ink. I wonder if red would help. I embark on a fruitless search for a red marker.

Isolation Day 26. My neighbor the musician has taken up drumming. I much preferred the guitar.

Isolation Day 27. A large brown envelope arrives from a friend in Macau. Inside, I find a pack of disposable surgical masks. Even though my friend advised me in January to stock up on face masks and hand sanitizer, I find no “I told you so” note inside the envelope. I send a text thanking him and telling him I recently found a 32-ounce bottle of hand sanitizer selling for $19. “Ah, capitalism,” he responds.

Isolation Day 28. During a meeting, I realize that Zoom spelled backward is mooZ. The meeting suddenly takes on a new meaning.

Isolation Day 29. I place an online order at Brits, a downtown store that sells all things British. (I don’t have to explain to anyone there what the Tardis is.) I have a hankering for digestives. They know what those are, too. The owner calls me. “I’ll leave the bag on the front step and run,” she says. It’s like having a May basket delivered. Or maybe she just saw the picture of me in the mask.

Isolation Day 30. Bzzzzzz. My Fitbit (bzzzzzzz) taunts me. Bzzzzzz. Time to get up and move, it says on the screen. It shows a perky stick figure stretching and leaping. “OK, where am I supposed to go?” I snarl. My smart speaker blinks blue. “I’m sorry. I’m afraid I didn’t catch that.”

Isolation Day 31. I read that anxiety from being shut in during the coronavirus can affect mood, work habits, even concentration. I’m not sure I b

Isolation Day 32. I assess the contents of the refrigerator: five lemons, a dribble of almond milk, a container of yogurt, a bottle of beer, a bottle of salad dressing, a bottle of ketchup and two plastic containers of unknown substances. I stare dolefully. I make a list. That’s all. I just make a list.

Isolation Day 33. I take my list and drive to the grocery store. I struggle to keep my mask on. I crane my neck, bob my head and push my nose upward like a bird drinking water. The cashier tries not to notice. Instead, she points at two giant containers of animal crackers on the conveyer belt. “How are your children doing amid this chaos?” she asks. Children? Oh, I say. One lives in Seattle. The other lives in Ontario. She looks again at the containers of animal crackers. I bob my head all the way to the exit.

Isolation Day 34. I woke up 14 times last night. I couldn’t stop bobbing my head.

Isolation Day 35. It’s the middle of the night. As I lift the toilet seat, it leaps from the single remaining rod securing it to the bowl. I lurch to catch it, bobbling the seat and jamming my shin into the bowl. The lid whacks the tank and lands like a horseshoe onto a plunger beside the bowl. Ringer! The seat whacks the floor with the force of a sledgehammer. “Are you all right?” my wife calls from the bedroom. I’m not sure how to answer. (Note to reader: You may question the use of leaps and sledgehammer in describing a toilet seat. Just remember. It is the middle of the night.)

Isolation Day 36. If I multiply the number of minutes I spend in Zoom meetings by the number of participants in those meetings, it equals the number of new email messages I receive during those calls.

Zm x Zp = ∞

I think I’m on to something big.

Isolation Day 37. The price of the Fake Me a Call Pro app has dropped to $6.49. It offers an extensive list of features, including a “custom fake call voice” and a “huge custom list of fake callers.” I imagine millions of people locked inside and fake-calling themselves. I’m not going to sleep again tonight. Am I?

Isolation Day 38. I stare at the faces in a Zoom meeting. Egads! Who is that squinty, raggedy-looking guy who desperately needs a haircut? Oh, wait. That’s me. Note to self: Apologize to colleagues for the visual fright I’ve caused.

Isolation Day 39. I have now logged more than 100 hours of Zoom meetings since seclusion began. I change my Zoom background back to the Tardis. Then I write “Change Zoom background” in green on the taunting whiteboard. Then I cross it out. For the first time in a month, I feel a sense of accomplishment.

Isolation Day Whatever. I finish grading. I should feel excited. I should feel so excited that I perform a hip-swaying dance in my slippers and post it on TikTok. Instead, I put on a mask, go to the hardware store and buy a toilet seat. Sigh. Now I have to install it.

Making iPad videos, using VoiceThread, and living a life of non sequiturs

Since the move to remote teaching this semester, several instructors have asked whether it is possible to use their tablets to make videos for students.

The answer is absolutely. I’m most familiar with using an iPad for making videos, but Android tablets work just as well if you have the right app.

Before I explain, I need to provide a caveat. The university’s IT staff doesn’t support the apps I mention here, so if you have to be willing to troubleshoot problems on your own. If you aren’t comfortable with that, use Kaltura, the university-supported video software. The Kaltura desktop software is easy to use and the IT staff can help you with any problems you might encounter.

I like working with a tablet for some types of video because a tablet makes it easy to draw by hand on the screen as you narrate. You can certainly do that with a touchscreen laptop, or with any computer if you are adept at mouse control (I’m not) or you have an input device like a Wacom drawing tablet.

Another benefit of a tablet is its portability. You can create video from almost anywhere. I recommend using a stylus rather than your finger to improve your writing and drawing. I’d also suggest using a headset or headphones with a good microphone. (If you use a USB headset, you will need an adaptor for an iPad.) The built-in microphone on the tablet will work, though.

Two apps for creating video instruction

The two presentation apps I like best are Explain Everything and Vittle. They are powerful tools for creating video presentations you can draw on and narrate. You can import PowerPoint slides and narrate over them, or create presentations within the app with shapes, text, imported media and a laser pointer. You can zoom in and out of the virtual whiteboard, and Vittle allows you to move elements around the whiteboard and capture the motion. Once you are done with a video, you render it as an mp4 file and then upload the file to Kaltura, YouTube or another video hosting platform.

Explain Everything also has collaboration features for classrooms where all students have tablets and access to the app. Vittle is for creation only. Both apps have free versions with limited functionality. I’d recommend downloading those and giving them a test drive. To make the apps fully functional, you will have to pay for them. Explain Everything costs $3 a month. The pro version of Vittle is a one-time cost of $25, although it occasionally goes on sale.

Using VoiceThread for peer editing

Melissa Stamer Peterson, a lecturer in the Applied English Center, has taken a creative approach to peer feedback by using VoiceThread to combine video, audio and student notes.

She starts by loading a short video lecture into VoiceThread. Students then upload their notes and share ideas via VoiceThread, which allows for responses with video, audio or text.

“What was really cool is that they were leaving feedback that I would leave,” Peterson told her colleague Carolyn Heacock in a video conversation that Heacock shared with me.

You can find the full conversation here. VoiceThread has many other examples of how instructors have used the software in classes.

And now for something completely different

That, of course, is the line made famous in Monty Python’s Flying Circus whenever the comedy troupe lapsed into a non sequitur about such things as the Ministry of Silly Walks, dead parrots, a man with three noses, or just the Larch.

The corona virus has turned life into an unending series of non sequiturs. People are stuck inside all day. They can’t go to work. They can’t go to school. They can’t hang out with friends. They are going crazy. I mean CRAZY.

So what do they do? They stack rolls of toilet paper in doorways and have their pets high-jump. It’s called the Level Up Challenge.

I am not making this up.

This should not be confused with the Level Up fitness challenge, which is on hiatus until gyms reopen, or with Ciara’s Level Up dance challenge, which dates to 2018 b.c. (that ancient time before corona) and which led to lunacy even before people were shut in.

This is the new Level Up Challenge, toilet-paper style. It’s hilarious. I’m just not sure where these people get so much toilet paper.

So if you are up for the Level Up Challenge, here are some starter videos.

If you prefer regular human high-jumping (for a world record, no toilet paper involved) …

Or if you prefer something completely different, try Jumping Jack Flash (c. 1968 b.c.)

A place for community during isolation from campus

With apologies to the late Warren Zevon, isolation is hardly splendid – at least when it is forced upon us.

I wrote last week about ways to create structure and belonging for students in online classes. Later in this post, you will find some information about student mental health, which was shaky even before the forced isolation.

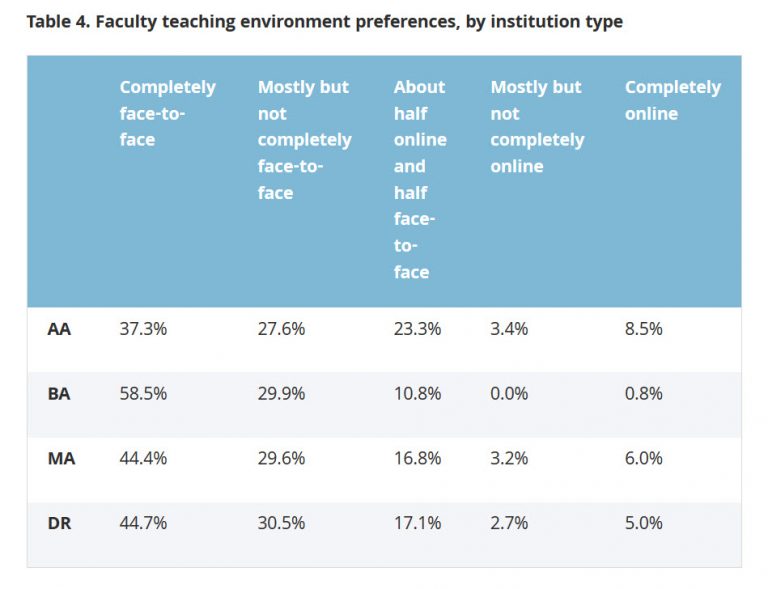

Faculty, too, are feeling the stress, of course. Few of them prefer to teach online, and most have actively avoided it. Now they have no choice, adding to the stress of a pandemic that has roared across the globe, an economy that has screeched to a halt, and a shortage of toilet paper that has – um, let’s not go there.

To help with the challenges of isolation and online teaching, the Center for Teaching Excellence has created a Faculty Consultant Network. This is made up of 13 instructors in 10 disciplines across the university who have experience in online teaching and digital tools. We see the network as an important way for instructors and GTAs to remain connected to the KU community during their time away from campus.

Andrea Greenhoot, the director of CTE, describes the network consultants as peer “thought partners” who can help colleagues in similar disciplines. They are available to meet remotely with colleagues and discuss strategies for teaching and working remotely. They will also help build community among instructors through regular online discussions that anyone can join.

You can find the list of peer consultants on the KU website for remote teaching. You can contact them directly or join their online office hours or open discussions, which are also listed.

An important change in Zoom

Some users of the videoconferencing tool Zoom have reported that outsiders have been able to gain control of meeting screens and display inappropriate material.

To prevent that, the company has changed the default setting on Zoom so that only a meeting organizer has screen-sharing privileges. The organizer can still allow others to display their screens, but the default of allowing anyone to share has changed.

Keeping an eye on mental health

Over the past few days, I have corresponded with students who have talked about being overwhelmed with the volume of communication from their instructors, from the university, from families, and from their children’s schools. Some have been caring for sick relatives in other states. Some are themselves sick. Still others say they are struggling with time management now that the structure of a daily routine has melted away and their children and significant others are stuck inside with them.

That’s just from a single class of 18. Multiply that by thousands, and you get a sense of the broad, personal impact the pandemic is taking on our students. Consider, too, that even before the current turmoil, student mental health was shaky.

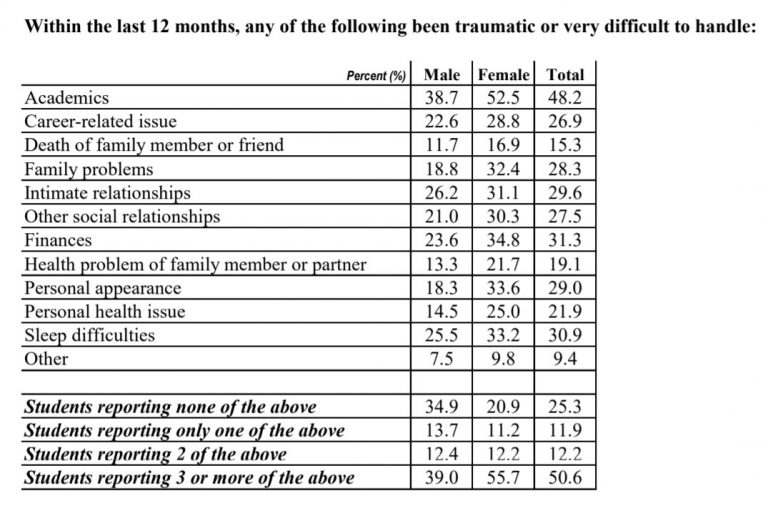

At an online workshop on Monday, Jody Brook, an associate professor of social welfare and a faculty fellow at CTE, offered this statistic for context: More than 60% of college students have had overwhelming levels of anxiety at some point in the previous year. Again, that was before the outbreak of Covid-19.

More than a quarter of students say that anxiety has hurt their academic performance, and 39% of men and 53% of women say that their academic work as been traumatic or difficult to handle in the previous year. These statistics come from the National College Health Assessment.

Brooks and Sydney Morgan, a counselor at Counseling and Psychological Services, said that everyone reacted differently to stress but that instructors needed to watch for these signs among students:

- Students who fail to respond to queries, fail to turn in assignments or suddenly perform worse in class.

- Students who express hopelessness or extreme anger, or who send lengthy rants to others.

- Students who express loneliness, fear or statements about death or suicide in their work.

Don’t be afraid to reach out to students, Brooks and Morgan said, but make sure to refer them to the right resources. CTE also has resources for instructors, and CAPS is also still available. Morgan said CAPS had been transitioning to appointments by phone. If students are out of state, CAPS will help the students find a counselor in their area.

Importantly, instructors need to be flexible and realistic with students. Brooks said that not only was flexibility important but that it was a requirement during a time of crisis. Most students will struggle with maintaining the same level of work they did before the social distancing began. Executive functioning diminishes during times of crisis, making it harder to focus, plan and get things done, Brook said.

That’s worth repeating: Increasing amounts of stress make it hard to focus and get things done. That applies to all of us.

So during this time of less-than-splendid isolation, take a deep breath and forgive yourself for failing to complete even one of the 978 tasks that have suddenly materialized on your to-do list. And consider that your students are facing the same challenges you are, but in different ways.

Helping students find their way through a fog of uncertainty online

The fog that settled on the Lawrence campus Monday morning seemed all too fitting.

Classes officially resumed after an extended spring break, but Jayhawk Boulevard was mostly empty, as were the buses that passed by. Faculty and students alike ventured into a hazy online learning environment cobbled together with unseen computer chips and hidden strings of code. Even the most optimistic took slow, careful steps onto a path with an uncertain end point.

We’re all feeling disoriented in this virtual fog, and it’s especially important for instructors to keep students in mind. Many of them had already been trying to maneuver through the seemingly amorphous landscape of college after relying on a highly structured school routine for much of their lives. Now even the loose structure of campus life has been yanked away.

We can’t change that, but there are some things we can do to help students succeed in the shift to online learning. None of it is difficult, but all of it will be important in helping students adjust.

Create some structure. One reason those of us at the Center for Teaching Excellence, the Center for Online and Distance Learning, and Information Technology have been stressing the use of Blackboard is that it provides a familiar landscape for students. Blackboard’s two biggest strengths are consistency and security. You may not like that consistency — personally, I find it like working within an aging warehouse – but the familiarity of Blackboard can provide a sense of stability for students. They know where to find assignments and they know where to submit their work. Many of them also obsessively check their grades there. Even if you use other online tools, Blackboard can provide a familiar base in the freeform environment of online learning.

Follow a routine. A routine also creates structure for students. For instance, will your class follow a traditional week? Will the week start on Tuesday when you usually had class? Will assignments be due at what would have been class time, or later in the evening? There’s no right answer to any of those questions. The important thing is to follow a routine. Make assignments due on the same days and at the same time each week. Put readings, videos and other course material in the same place each week. Use the Blackboard calendar to list due dates or provide a list of due dates on the start page for your course.

Communicate often. Students are stuck at home just as you are, and they are without the visual and oral cues they rely on from their instructors. That makes it all the more important to communicate. Post announcements on Blackboard. Send email. Set up times when students can call you or reach you through Zoom or Skype. You don’t want to be annoying with constant messages, but you want to make sure students know they can reach you if they need you.

I have found that a weekly message to students can also help create routine. That weekly message reminds students that a new week has begun and that they need to be paying attention to a new set of assignments. I start by providing an overview of the readings, videos and other material students must cover for the week. I also list any assignments due that week and remind students of important due dates coming in the weeks ahead. Then I provide a bit of the unexpected. I share interesting articles, books, podcasts, photos, videos or websites I have found. Sometimes those are related to class material. Other times, they are totally random. My only criterion is that the material is interesting or entertaining.

Ask for their thoughts. More than ever, it is important to seek feedback from students. What is working in the class? What isn’t? Can they find the readings? Do they understand the assignments? Do they have ideas on how to make the class go more smoothly? Everything you are doing in a class may seem clear and logical to you, but students may be lost. So ask them what might help. Create a place on Blackboard for students to submit questions. Create a poll with Qualtrics.

I’ve created a discussion assignment each week on Blackboard where I ask students to share their observations about the switch to online learning. Many of my students are graduate teaching assistants, and I want a place where they can share their experiences with teaching online for the first time but also with how their students are responding to the changes. I’ve never tried anything like this before, so I’m not sure what to expect.

Amy Leyerzapf of the Institute for Leadership Studies has created a “self-care” area on Blackboard for the students in her freshman seminar. This includes a “self-care discussion forum and a collection of carefree bits and pieces, many of them from posts floating around on social media,” she said via email. It also includes links to online cultural sites like streaming opera, museum tours and webcams from zoos and aquariums. There are links to material about mental health resources, at-home exercise and meditation. Importantly, there’s a recipe for peanut butter cookies.

“I’m hoping that it will evolve as students contribute ideas via the discussion forum and I run across more nuggets,” Leyerzapf said.

It seems like a magnificent approach to helping students cut through the haze.

To give your online class a bit of campus feel, add a virtual whistle

It’s the little things we miss when our routines change.

It’s the one on display in the Kansas Union.

As classes move online, those little things will add up for faculty, staff and students. We won’t bump into colleagues along Jayhawk Boulevard. There will be no chalking on sidewalks on Wescoe Beach, no sound of the fountain on West Campus Drive, no view of the Campanile over Potter Lake, no smell of books in the stacks at Watson Library, no view of the flags atop Fraser Hall.

We can build community in our classes and maintain connection with our students and our colleagues. We can’t provide access to all those little things that form a sense of place, though.

There is one little thing I thought might help, though: the sound of the steam whistle.

The whistle, which marks the end of each class period, went silent over spring break, and it hasn’t resumed. After all, there are no classes to signal an end to, no students staring at clocks in lecture halls and waiting to hear the sultry wail of escape echoing across Mount Oread.

And yet, with a pinch of imagination and a dash of digital magic, we can still share the whistle with our students. You will find links to video and audio clips below. They come from a longer video about KU traditions that the university posted in 2011. John Rinnert in IT was able to get a copy for me, and from that I created the snippets you’ll find here.

Feel free to add them to your Blackboard site or share them with your students in other ways. It’s a little thing, but little things matter in times of turmoil.

Creating community in an online course

One aspect of online teaching that I feared would make it less enjoyable for me as an instructor is that my students and I wouldn’t get to know one another as well as we do in our in-person courses.

I thought that it would be difficult to replicate the interaction and dynamic atmosphere of a classroom where we all exchange ideas, participate in thoughtful discussions, challenge each other’s beliefs and positions, develop an understanding of and respect for one another, and come to care about each other as fellow humans.

As I have developed new courses and adjusted and redesigned old courses, though, I have found that creating a real sense of community is possible. To do that, I keep coming back to three general areas. I use them from the start of my online classes, but they apply just as well in a class that is moving online midterm, as we all are doing now.

These are easy to implement, are viewed positively by students, and can even help to reduce the grading burden on the instructor in some instances. Additionally, these techniques do not take away from the time and attention needed for students to interact with the course content in a fast-paced term. In fact, the engagement that results benefits students’ processing of the material as they interact with their classmates.

Establish early contact with students

Reach out to students as soon as possible and encourage them to familiarize themselves with the course components, and establish an expectation that they will be involved in your online class community. It is important that students “hit the ground running” on Day 1 and this early admission into the online course allows them to get ready for what can be a busy and demanding few weeks. It also establishes that you expect them to do a little work up front to be prepared to participate in your course and to interact with you and with their classmates. Here are some examples of how I encourage this early participation and preparation by my students:

- Welcome email: When I turn on the course, I post an announcement and send an email that welcomes students to the course. This email gives them the basic information about how to get started by accessing the course website and where to go from there. I also express my enthusiasm about teaching the course and getting to know them. There is plenty of room for policies and procedures in the course website and syllabus. Use this first contact with students as an opportunity to be friendly and approachable, not to warn them about all the pitfalls of not being prepared or doing the coursework.

- Getting Started section: Once students log into the course website, it is important that they have a detailed roadmap for what you expect them to do before Day 1. Taking the time to build this roadmap for your students will ensure that they are prepared and understand your expectations.

- Welcome video: Making a welcome video seems somewhat unnecessary from a course content perspective but it can go a long way toward students’ seeing you as an approachable, real-life person who wants to engage with your students. This may not be possible in the short time you have to make your class available online this semester, but look for ways like this to remind students that the same person is running the class.

Have an assignment due soon after the course goes online

This assignment is not about the course content. Rather, it is a chance for students to re-introduce themselves to you and to each other. It also helps them become familiar with some of the tools you will use on Blackboard.

Create your own example to share with your students about yourself. Students then get a feel for the people they are interacting with. They can share pictures and learn about families, interests, backgrounds, and jobs. They can see connections between themselves and the life experiences of the people with whom they are enrolled in the course. They can even comment or interact with one another as a way to say hello. Here are two ways that this would be easy to implement and also might allow students practice at using a system or technology that you use later on for actual coursework:

- About Me slide: This version of the assignment asks students to create a slide where they share information and pictures about themselves with you and their fellow classmates. I have used PowerPoint to create my example slide for my courses, but some students simply paste pictures into a Word document. For my example, I include pictures of my family on vacation, pictures of pets, lists of hobbies and interests, and background information about my life. I post my slide as an example with the assignment description. Students can post their slides to a discussion board and then might be required to introduce themselves to another classmate or even find some similarity with a classmate to ensure early interaction.

- VoiceThread introduction: Instead of creating a static slide with pictures and text information, you could use VoiceThread for these early introductions. This method would be especially useful if you plan to use VoiceThread as a course component as it would allow practice with the technology. Students could introduce themselves to one another using their computer webcam. They could show pictures and talk about interests, family, and experiences without it being time-consuming to build. This format also has the potential to increase student involvement. Students might be more likely to watch their classmates’ videos because it is easier than clicking through and reading individual slides for each person

Create smaller communities within your online class

Thus far I have focused on how to set the expectations for engagement early on. Maintaining that feeling of community and requirement for engagement is the focus of this last area.

Many students take online classes because they want to work independently and learn the content in a way that is most efficient and flexible given their life circumstances. However, learning in isolation is not always the best way to fully master and understand the content. Therefore, it is my job as the instructor to build this engagement between students into the course design. I have found that creating smaller communities within an online class can be very effective. Students can get to know a subset of their classmates and participate in assignments and discussions with the same people throughout the semester. This can be accomplished by forming groups or teams of 6-10 students. Assignments that require peer interaction can then be designed to work within this smaller group as opposed to on a class-wide scale. Here are some ways I have used this approach with different assignments in my courses:

- About Me slide. I have students share their About Me slide only with their smaller discussion group and not with the class as a whole. This feels like a more intimate introduction and helps to establish this smaller team from the beginning.

- Written assignments with peer review. We all want our students to practice sharing their thoughts about the course content in written form. However, reading and providing feedback on weekly written assignments can be a very big time commitment for the instructor. Instead, it can be useful to have students peer review each other’s assignments. This system helps to ensure quality without the instructor having to read every assignment every week. Even better, students not only receive very timely feedback on their assignment but they also get to experience what a classmate thought about that week’s topic. This engagement with one another is like having a conversation in class where they can agree or disagree on some topic. Students then can write a reflection that highlights those similarities or differences that they identified. This system can be introduced at the smaller discussion group level, which ensures that students are interacting with the same group of classmates and that those feelings of community can be strengthened and maintained throughout the course.

- Group discussion assignments. Another option for creating engagement with the smaller community is to have weekly discussion topics or prompts that all students must answer within their group. Students must respond to the instructor’s discussion topic(s) by an early due date within that week’s schedule. Group members must then return to the discussion board later in the week to respond to and engage with a classmate about the topic. Again, doing this in a smaller group setting allows for a sense of community, and students get to know one another better than if it is designed to encompass the entire class.

- Afterthoughts assignments. An important goal in my classes is for students to connect the content to their daily lives. I have also used this smaller discussion group setting to get students to make these connections and to decide, as a group, what example might be the best that is presented in a given week among their members. Students are required to post an “afterthought” about the topic(s) we are covering that week on their group discussion board. This post could be a picture or video that illustrates a concept. It could be a link to something they came across on the internet. It could be a text description of something that happened to them. Students must post their “afterthought” to their discussion board and then all group members must return to vote on which one they think is the best example presented that week. They also comment to justify why they voted for a given post. In this way, the smaller group can come together to make a decision about what post might be one that is highlighted by me to the rest of the class.

I feel like I am constantly searching for new ways to engage online students. I want this engagement to benefit their learning and experience in the class and also to make teaching online classes more enjoyable for me. In that search, I have tried many different techniques and some have failed miserably. The ones I have discussed here, however, have stood the test of time and have lived on in various forms, in a variety of courses, and have been useful for different types of content.

When you teach online, nobody laughs at your boots

This is what teaching online looks like.

That’s not quite right. This is what planning for teaching online looks like after a week and a weekend of long days and an early meeting on Monday morning.

About noon, I looked down and realized I was wearing mismatched boots. Some people wear mismatched socks. I wear mismatched boots.

Rather than hide them, I showed them to everyone I met on what was probably the last day of in-person meetings for quite some time. I emailed the photo to colleagues and to my students. Everyone needed the laugh.

“We’re not really laughing at you,” Diana Koslowsky, the administrative officer of the School of Public Affairs and Administration, said after I pulled my feet from beneath a conference table and held them up. “It’s just …”

“We know what it’s like,” said Ward Lyles, an associate professor in the school and a faculty fellow at CTE.

I held up my hands.

“It’s all right,” I said. “Laugh. We all need it.”

Tensions are high right now as the corona virus spreads and instructors scramble to put their courses online. Anxiety lurks on every surface. Encounters with others are awkward as we maintain a distance but still try to be social.

Despite the turmoil, we can’t lose our sense of humor. Laughter is important for maintaining a bond of shared humanity. It’s important for pushing aside the tension, if only briefly.

So laugh at yourself. Laugh at the absurdity of the circumstances. Laugh at Michael Bruening from Missouri University of Science and Technology as he sings “I Will Survive” online teaching. Laugh at my mismatched boots.

I want you to know, though, that even in mismatched boots, I was able to get done everything I needed to get done. My boots may have looked absurd, but I at least put them on the right feet. Mismatched or not, my boots still pointed forward.

Online, nobody knows …

In 1993, The New Yorker published a Peter Steiner cartoon with a caption that said, “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.”

The cartoon captured the doubts about a growing online culture and the anonymity it represented.

With apologies to Steiner, I offer a remake of the original. I’ll let you decipher it for yourself. I will say, though, that when you teach online, nobody laughs at your boots.

You can complain or you can model. Which will your students see?

Take a deep breath. You are about to launch into an online adventure.

Yes, I know, you didn’t want to take this trip. The corona virus – and the university – made you do it. Like it or not, though, we are all on the same trip, one that will take us deep into the uncharted territory of a quickly deployed online teaching and learning matrix of enormous scale. This involves not just the University of Kansas, but hundreds of colleges and universities around the world.

Despite the less-than-ideal circumstances, you can still help your students learn online. Despite your wariness of the medium, you can succeed as an online teacher. I’m not trying to be Pollyannaish. (Maybe a little.) Rather, I see this as an opportunity for all of us to break out of ruts we get into in the classroom, examine what we want our students to learn, and consider new ways of accomplishing those goals.

We also have an opportunity to model the types of behavior we want our students to adopt in the face of adversity. They will encounter many challenges in their lives, just as we have, and they are looking to us for guidance not only on college-level learning but on coping with the realities of a global pandemic, economic turmoil, social distancing, and sudden isolation in a world that had been growing more closely connected.

Are you up to the challenge?

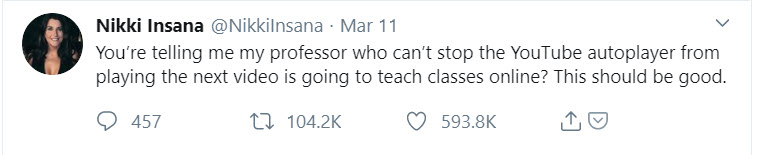

Many students don’t think you can do it. . Here’s what one of them had to say last week on Twitter.

“You’re telling me my professor who can’t stop the YouTube autoplayer from playing the next video is going to teach classes online? This should be good.”

That post has been retweeted more than 100,000 times and had drawn nearly 600,000 likes by the weekend. It also attracted a slew of similarly frustrated students who poked fun at their teachers’ technical inadequacies with online grade books, YouTube, web browsers, volume controls, email, and seemingly anything that worked with bits and bytes. (My favorite: The instructor who uses Yahoo to search for Google so he can search for something he wants to show the class.)

“I have no expectations for ANY of my teachers,” one student wrote.

“Pray for the IT department,” wrote another.

Teachers fired back with their own zingers. One wrote:

“You’re telling me my students who can’t pay attention for 2 minutes even while I practically hold their hand through new content are going to have to learn on their own time? This should be good.”

‘We’re all trying really hard’

As the number of zingers grew, though, the tenor of the conversation began to shift. More instructors and instructional designers began to chime in. Many of them had their own doubts about whether this enormous online experiment would work.

Some talked about the overwhelming task of moving classes online at the last minute. An adjunct who teaches at several schools, each with a different online system, said she was struggling to figure out how to get her classes up and running. Retired professors expressed compassion for their former colleagues, with one saying the reason he retired was that he was no longer up to the technological challenge. Others pleaded for patience.

“We’re all trying really hard,” one instructor said.

Instructional designers wrote about putting in long days to try to make the switch possible. One wrote: “You’re the reason I do this work. I promise I’m doing my best for you.”

A time for compassion

In a single Twitter thread, you see nearly all the directions the next few weeks could take: humor, anxiety, sniping, denial, helplessness, surrender, bitterness, resolve and, yes, even hope.

“Oh, have a heart,” said Jenna Wims Hashway, a law professor at Roger Williams University in Rhode Island. “We’re doing the best we can. I say this as someone who is absolutely certain to screw up this technology that I’ve never used before. But I’m willing to try anything and look like an ass if it means I can teach my students what they need to know.”

No one has all the answers you are looking for as you try to figure out how best to transfer your classroom work online. (There is lots of help available, though.) Students are just as worried as you are about what this will mean for their classes, their learning, their degrees, their graduation, and their lives.

It’s up to you to model what you want to see in your students. If you complain, they will complain. If you show a sense of humor, many of them will still complain. Expect that, and move beyond it.

What you can do

We are taking on what The Chronicle of Higher Education called “the great online-learning experiment” as we are being told to distance ourselves physically from others. That’s intimidating and mentally taxing for instructors and students. Here are some ways you can break through that.

Don’t let the physical distance become mental distance. Campus is strangely silent. The hallways in our buildings are empty. Many of us are working from home. Many of the regular social activities we rely on have been shut down. All of that isolation can take a mental and emotional toll if you let it. So remember to engage with colleagues and your students. Share your feelings. Ask for help when you need it. Join the many workshops we will have on campus and online this week or the many online communities that have popped up to help with online teaching. And take a walk occasionally. Spring is nearly here. Your teaching has become virtual, but you still live in a physical world.

Give yourself a break. One of the challenges of online teaching is that it can feel like class is always in session. You have to set boundaries and establish new routines. Decide when you will engage with class work and when you will do other things. Tell students when you will be available and when you will not. And set aside time for yourself. Don’t let the things that keep you mentally and physically agile slip away.

Work at creating community. This is perhaps the most important thing you can do in any class. Students need to feel that they are part of a learning community. They need your trust and your guidance. They need to know you have a plan – even a tenuous one – to make this work. They need to know that a human being is paying attention beyond the glow of the computer screen. So communicate with students often through whatever means works best for your class. Keep them apprised of your plans. Tell them to expect lots of twists and turns. Tell them that you will be flexible with them and that they should be flexible with you. And remind them not to let the physical distance become mental distance – and to give themselves a break.

Where to find assistance

Remember, you don’t have to do this alone. There is an abundance of resources available and many people to offer assistance. The best teaching and learning happens as part of a community, and CTE, the Center for Online and Distance Learning, and KU Information Technology are working to bolster that community. We have planned several workshops over the coming week (with more to follow). You’ll find those, along with many other resources to guide you into online teaching, on a new website we created last week.

If you haven’t visited the site, you should. It’s a great place to start if you’ve never taught online before, and it’s a great place to get new ideas if you have. If you need help, the site provides contact information for those of us who can help. We will continue to add material and update the workshops we are planning over the coming weeks. I will also be providing advice through this blog, trying to address myths about online teaching, offer ways to create community in online classes, and suggesting tools you might try to Also let us know what you want to know about online teaching so we can provide the types of materials you and your colleagues need.