WASHINGTON – As colleges and universities prepare to encounter what has become known as a cliff in traditional student enrollment, they are looking for ways to reach out, branch out, and form partnerships that might once have been unthinkable.

That desire to branch out was clear from the sessions I attended at the annual meeting of the Association of American Colleges and Universities. For instance, speakers at the conference urged colleagues and their universities to:

That desire to branch out was clear from the sessions I attended at the annual meeting of the Association of American Colleges and Universities. For instance, speakers at the conference urged colleagues and their universities to:

- Do a better job of working with community colleges, whose lower cost is appealing to students, most of whom want to continue at four-year institutions.

- Reach out to high school students and introduce them to liberal education before they choose a college and a major.

- Draw in older adults, reintroduce them to learning as they move into a new phase of life, and draw on their expertise in classes and career development.

- Create stronger partnerships with other colleges and universities.

- Create better strategies for telling the story of higher education.

There’s no secret about why branching out is important. At a session titled “Responding to the Crisis in Higher Education,” Elaine Maimon, president of Governors State University in Illinois, said “crisis” had appeared in AAC&U session titles nearly every year in the decades she had been attending the conference. (Maimon was facing her own crisis back home.) Even so, she said:

“I’m ready to say the revolution is here.”

‘Stop rehearsing our dilemmas’

I’ve written considerably about the idea of “revolution” in higher education, about the need for universities to adapt and change, and about the plodding approaches that higher education as a whole has taken to the broad challenges.

In short: The number of traditional students is declining, especially in the Midwest and Northeast. Demographic shifts have created what one AAC&U participant called “a new student majority” made up of first-generation students, students of color, adults, and military veterans, and many of those students start at community colleges. State and federal funding has plummeted. And digital technology has created what Maimon called “an epistemological revolution in terms of ways of knowing.”

Mary Dana Hinton, president of the College of Saint Benedict, said colleges and universities needed to stop “stop rehearsing our dilemmas” and work at making changes.

“We know what our problems are,” Hinton said. “We need to change, and to invest in our faculty, our staff and our leadership so that we create environments and spaces where every student on our campus can see themselves, can feel appreciated, can be challenged and transformed, and that we as institutions are transformed by the students who come to us.”

The sort of transformation that Hinton referred to has many components.

Working with community colleges

Scott Jaschik, editor of Inside Higher Ed, emphasized the importance of making connections with community colleges because “that’s where the students are.”

Most Americans who earn a bachelor’s degree start at community college, Jaschik said, and four-year institutions need to make transfer easier and create welcoming environments for community college students. Some states are also making community college free, he said, an idea that has transcended political ideology.

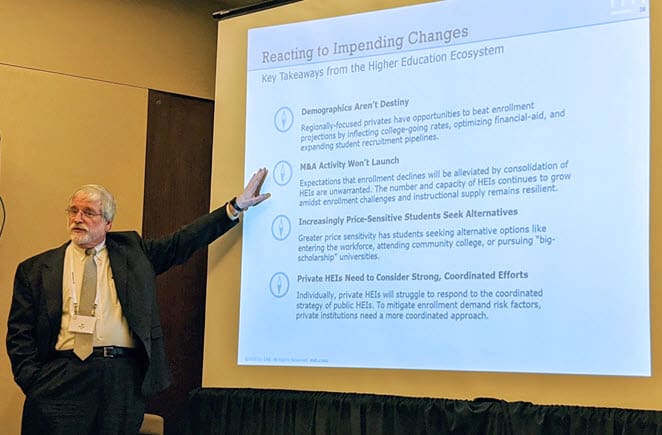

Cost is playing a big part in students’ decisions. Al Newell of the education research company EAB said that the lower cost of community colleges had great appeal to Generation Z, which he described as thrifty and frugal. More than 40% of students whose families earn at least $250,000 a year are considering community colleges, Newell said, with some looking at college as a seven- or eight-year investment if students go to graduate school.

Twenty years ago, he said, students aspired to attend the best school they could get into. Now, he said, students’ mindset is that they will go to the best school that they can get into and that their families can afford.

An announcement last week underscored the importance of community colleges. Southern New Hampshire University, a large provider of online education, offered students of Pennsylvania’s community colleges a 10% tuition discount, a move that is expected to draw students away from the state’s four-year institutions.

A different approach to adult education

A new model for bringing adults into college courses has begun to emerge.

Colleges and universities have offered continuing education classes for adults and retirees for many years. Since the early 2000s, KU and many other universities have been involved in the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, which focuses on adults age 50 and older. What’s different this time is that universities are creating longer and more intensive programs for older adults, integrating them into traditional classes and activities, and using their expertise to enrich discussions and career preparation.

Longevity is changing workers’ outlook, and many of those in the baby boom generation are looking for new paths after they retire, Kate Schaefers, executive director of the Advanced Careers Initiative at the University of Minnesota, said during an AAC&U panel discussion. Minnesota is one of several universities that have created programs for late-career or retired professionals. Many of those are modeled on Stanford’s Distinguished Careers Institute, which brings in a small cohort each year and helps each participant shape an individual curriculum built on their interests. It integrates them into traditional classes but also creates separate seminars, colloquia and other events. That approach has been successful enough that Stanford is planning to create a non-profit organization to help universities create similar programs, participants at an AAC&U panel said.

Organizers use words like “transformative” to explain the rich opportunities these new programs provide and the powerful bonds they create. The programs are also expensive: often $60,000 a year or more. Most programs offer financial aid for a few fellows, but organizers say the cost reflects the need to be self-sufficient.

Reaching out in other ways

Conference panelists talked about the need to reach out to many other constituencies, including businesses, rural students, low-income students, students of color, non-traditional students, and international students, whose numbers have declined over the past few years.

Colleges and universities start sending promotional material to prospective students early in high school. Later on, they encourage families to tour campuses and to talk with advisors. Those approaches help get a school’s name in students’ mind and help students get a sense of a school’s atmosphere. What they fail to do, though, is to help students understand what happens within a particular discipline.

Andrew Delbanco, president of the Teagle Foundation and a professor at Columbia, said universities needed to create opportunities to bring high school students – especially those from underserved populations – to their campuses for a week or more and engage them in intensive humanities seminars that explore the depth and breadth of liberal education. That approach, which Teagle has been funding, helps students “learn that college is not only about getting a job.” It also helps faculty members, graduate students and undergraduates better understand the perspectives of underserved students.

“We all agree in this room about the value of liberal education,” Delbanco said. “But we have a problem. You cannot explain the value of liberal education to someone who hasn’t had one. You can’t do it. … You cannot convey the taste of honey to someone who hasn’t tasted it.”

The importance of that type of approach was reinforced by statistics at Newell’s session. A survey of 5,200 students at Chicago public schools found that in ninth grade nearly all students aspired to college. By the 11th grade, that dropped to 72%. By 12th grade, 59%. In the end, only 41% enrolled in college.

He cited many reasons for the drop-off: lack of role models who have gone to college; exclusion from advanced placement classes; lack of understanding of the enrollment process; failure to take required courses; and lack of money.

“The reality is that the way we do business is going to have to adapt,” Newell said.

He gave several examples of how colleges and universities were adapting. One of the most prominent is through partnerships with or acquisitions of other institutions. In some cases, university systems are requiring consolidation. In others, a university acquires a nearby struggling institution in what Newell describes as a “goodwill grace merger.” In still others, the acquisitions are pure business deals, or “strategic capital asset acquisition,” as Newell described them. (Think of Purdue’s purchase of Kaplan.)

We also need to keep lobbying skeptical legislators and talking more to a skeptical public, Delbanco said — and working more closely with local communities.

It’s a daunting challenge, but AAC&U sessions seemed far more upbeat than they have been in the past few years, even as Delbanco summed up an admonition that was repeated by several others:

“Colleges and universities must serve young people – and not only young people – beyond their gates more effectively,” he said.

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.