A student view of effective teaching

AUSTIN, Texas – How do students view effective teaching?

They offer a partial answer each semester when they fill out end-of-course teaching surveys. Thoughtful comments from students can help instructors adapt assignments and approaches to instruction in their classes. Unfortunately, those surveys emphasize a ratings scale rather than written feedback, squeezing out the nuance.

To address that, staff members from the Institute for Teaching and Learning Excellence at Oklahoma State spoke with nearly 700 students about the effectiveness of their instructors and their classes. They compiled that qualitative data into suggestions for making teaching more effective. Christina Ormsbee, director of the center at OSU, and Shane Robinson, associate director, shared findings from those surveys last week at the Big 12 Teaching and Learning Conference in Austin.

Here are some of the things students said:

- Engage us. The students’ favorite instructors vary their approach to class, use interesting and engaging instructional methods, and use relevant examples.

- Communicate clearly. Students value clear assignments, transparent communication, and timely, useful feedback. They also want lecture notes posted online.

- Be approachable. Students described their favorite instructors as personable, professional and caring. “Students really want faculty to care about them,” Ormsbee said. They also want instructors to care about student learning. They complained about instructors who were abrasive, sarcastic or demeaning.

- Align class time with assessments. Students want instructors to respect their time by using class activities and lessons that connect to out-of-class readings and build toward assessments.

- Be available. Students want instructors to hold office hours at times that are convenient for students and to help them when they ask. They also expect instructors to communicate through the campus learning management system and though email and other types of media.

- Be organized. Students appreciate organizational tools like detailed class agendas and timelines. They like study sessions before exams, but they also want instructors to go over material they missed on exams.

- Slow down. Students say instructors often go through course material too quickly.

- Grade fairly. Students dislike instructors who focus grading too heavily on one aspect of a course, grade too harshly, or deduct points for missing class or for not participating.

- Don’t give us too much work. (You aren’t surprised, are you?)

Much of this aligns with the research on effective teaching and learning (engagement, alignment, organization, pacing, transparency, clarity). Some of it also aligns with aspects of universal design for learning (see below). Other aspects have as much to do with common courtesy as with good pedagogy. (We all want to feel respected.) Still other parts reflect a consumer mentality that has seeped into many aspects of higher education.

Feedback from students is important, but it is also just one of many things that instructors need to focus on. A class of satisfied students means nothing if none of them is learning. And students know little about the years of accumulated evidence about effective teaching. So we should listen, yes, but we should base decisions about our classes on an array of evidence and thoughtful reflection.

Universal design takes center stage

All too often, instructors, administrators and staff members think about accessibility of course content only when a student requests an accommodation.

The problem with that approach, said Melissa Wong of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, is that a vast majority of students who need accommodations never seek them out. Sometimes they don’t know about a disability or have never been formally diagnosed. In other cases, students are embarrassed about having to share personal details or assume they can make it through a class without an accommodation.

Wong called the current system of acquiring an accommodation “legalistic.” Students must have health insurance. They must fill out multiple forms and have records transferred. They must maneuver through university bureaucracy and find the right offices, a skill that many students lack. Then they must submit forms in each class they take. In class, they may confront inaccessible course materials, hazy expectations, and daunting assignments.

Each of those barriers adds to students’ burden, ultimately making things harder for instructors and for other students. Instructors can help all their students – even those who don’t need accommodations – by following the principles of universal design for learning, though, Wong said. Wong was among several speakers at the Big 12 conference who emphasized the importance of universal design for learning.

Universal design started with architecture (think curb cuts and self-opening doors), but its importance in education has grown as the diversity of students has grown. In essence, it is a way of thinking about learning in terms of student choices: multiple forms of engagement, multiple means of representation, and multiple forms of action and expression.

Tom Tobin of the University of Wisconsin-Madison suggested thinking of universal design in terms of “plus one.” If you have a written assignment, consider giving students one other option for completing the same work. If you provide a video, make sure it has captions.

“We don’t have to perfect,” Tobin said. “We just have to be good."

He also suggested reframing the conversation about accessibility to one about access. Good access helps all students learn more effectively and keeps them moving toward graduation.

“The idea of UDL is not to lower the rigor of the material,” Tobin said. “The idea is to lower the barrier of getting into the conversation in the first place.”

Wong offered some additional advice on how to apply universal design in classes:

- Use a clear organizational structure in your syllabus. Use subheads so that students can find everything easily. And make sure the syllabus has a section on accommodations.

- Create a list of assignments and due dates. This helps students plan and cuts down on anxiety. Wong said a one-page assignment calendar she creates was one of the most popular things she had done for her classes.

- Present information in a variety of ways (text, video, audio, multimedia), and provide examples of successful work. Offering choices in assignments can help students feel more in control and allow them to demonstrate learning in ways they are most comfortable with. For instance, you might give students a range of assignment topics to choose from and give them options like video or audio for presenting their work, in addition to writing.

- Make sure video is close-captioned. If you have audio, make sure students have access to a transcript.

- Use a microphone routinely, especially in large classrooms.

- Scaffold assignments so that students can work toward a goal in smaller pieces.

- Be flexible with deadlines. If you give one student an extension, make sure all students have the same option. If a student is chronically late with assignments or frequently seeks to make up work, try to understand the underlying problems and refer that student to offices on campus that can help.

The best approach is to take accessibility into account from the beginning rather than trying to retrofit things later, Wong said. That not only cuts down on the need for accommodations but creates a smoother route for all students.

Other nuggets from the conference:

Supplemental instruction success. A three-year study at the University of Texas-Austin found that student participation in supplemental instruction sessions improved grades in gateway courses in electrical engineering. Supplemental instruction involves regular student-led study sessions overseen by trained student facilitators. About 40% of students in UT’s Introduction to Electrical Engineering courses participated in supplemental instruction. I’ll be writing more about KU’s supplemental instruction program in the next few weeks.

Practical thinking. Shelley Howell of the University of Texas-San Antonio emphasized the importance of relevance in helping students move toward deeper learning. She drew on a model from Ken Bain’s book What the Best College Students Do, categorizing students into surface learners (who do just enough to get by), strategic learners (who focus on details and stress about grades) and deep learners (who are curious and ask questions, accept failure as a part of the learning process, and apply learning across disciplines). All students need to understand the purpose of individual assignments, and instructors need to make course content relevant, give students choices, and ask questions that take students on a “messy” path to understanding, Howell said.

Red alert. Educators have grown too complacent about student failure, Howell said, and would benefit from a Star Trek approach to student success. Every episode of Star Trek is essentially the same, she said: Something goes wrong. The problem must be fixed right away or the ship will crash. The problem is impossible to fix. The crew finds a way to fix it anyway. What if those of us in higher education had the same attitude? Howell asked, adding: If you knew that every student had to succeed, how would you teach differently?

A final thought. Emily Drabinski, a critical pedagogy librarian at the Graduate Center at City University of New York, offered this bit of wisdom: “For knowledge to be made, it has to be organized.”

A teaching event grows into a celebration

When we started an end-of-semester teaching event four years ago, we referred to it simply as a poster session.

The idea was to have instructors who received grants from the Center for Teaching Excellence or who were involved in our various programs create posters and then talk with peers and visitors as they might at a disciplinary conference. In this case, though, the focus was on course transformation and on new ways that instructors had approached student learning.

As the event grew, we decided to call it the Celebration of Teaching, and it has become exactly that.

We didn’t do an official count at the event on Friday, but well more than 100 people attended. There were 54 posters created by instructors involved in Diversity Scholars, the Curriculum Innovation Program, and the Best Practices Institute, and those who received course transformation grants during the year.

Here’s view of the Celebration of Teaching in photographs.

4 ways to increase participation in student surveys of teaching

If you plan to use student surveys of teaching for feedback on your classes this semester, consider this: Only about 50% of students fill out the surveys online.

Yes, 50%.

There are several ways that instructors can increase that response rate, though. None are particularly difficult, but they do require you to think about the surveys in slightly different ways. I’ll get to those in a moment.

The low response rate for online student surveys of teaching is not just a problem at KU. Nearly every university that has moved student surveys online has faced the same challenge.

That shouldn’t be surprising. When surveys are conducted on paper, instructors (or proxies) distribute them in class and students have 10 or 15 minutes to fill them out. With the online surveys, students usually fill them out on their own time – or simply ignore them.

Response rates on teaching surveys at KU, 2015-2018

Student participation in end-of-semester teaching surveys has fallen as the surveys have moved online. Many instructors still report rates of 80% to 100%, but overall rates range between 50% and 60%. These rates reflect only the surveys that were taken online.

I have no interest in returning to paper surveys, which are cumbersome, wasteful and time-consuming. For example, Ally Smith, an administrative assistant in environmental studies, geology, geography, and atmospheric sciences, estimates that staff time needed to prepare data and distribute results for those four disciplines has declined by 47.5 hours a semester since the surveys were moved online. Staff members now spend about 4 hours gathering and distributing the online data.

That’s an enormous time savings. The online surveys also save reams of paper and allow departments to eliminate the cost of scanning the surveys. That cost is about 8 cents a page. The online system also protects student and faculty privacy. Paper surveys are generally handled by several people, and students in large classes sometimes leave completed surveys in or near the classroom. (I once found a completed survey sitting on a trash can outside a lecture hall.)

So there are solid reasons to move to online surveys. The question is how to improve student responsiveness.

I recently led a university committee that looked into that. Others on the committee were Chris Elles, Heidi Hallman, Ravi Shanmugam, Holly Storkel and Ketty Wong. We found no magic solution, but we did find that many instructors were able to get 80% to 100% of their students to participate in the surveys. Here are four common approaches they use:

Have students complete surveys in class

Completing the surveys outside class was necessary in the first three years of online surveys at KU because students had to use a laptop or desktop computer. A system the university adopted two years ago allows them to use smartphones, tablets or computers. A vast majority of students have smartphones, so it would be easy for them to take the surveys in class. Instructors would need to give notice to students about bringing a device on survey day and find ways to make sure everyone has a device. Those who were absent or were not able to complete the surveys could still do so outside class.

Remind students about the surveys several times

Notices about the online surveys are sent by the Center for Online and Distance Learning, an entity that most students don’t know and never interact with otherwise. Instructors who have had consistently high response rates send out multiple messages to students and speak about the surveys in class. They explain that student feedback is important for improving courses and that a higher response rate provides a broader understanding of students’ experiences in a class.

To some extent, response rates indicate the degree to which students feel a part of a class, and rates are generally higher in smaller classes. Even in classes where students feel engaged, though, a single reminder from an instructor isn’t enough. Rather, instructors should explain why the feedback from the surveys is important and how it is used to improve future classes. An appeal that explains the importance and offers specific examples of how the instructor has used the feedback is more likely to get students to act than one that just reminds them to fill out the surveys. Sending several reminders is even better.

Give extra credit for completing surveys

Instructors in large classes have found this an especially effective means of increasing student participation. Giving students as little as 1 point extra credit (amounting to a fraction of 1% of an overall grade) is enough to spur students to action, although offering a bump of 1% or more is even more effective. In some cases, instructors have gamified the process. The higher the response rate, the more extra credit everyone in the class receives. I’m generally not a fan of extra credit, but instructors who have used this method have been able to get more than 90% of their students to complete the online surveys of teaching.

Add midterm surveys

A midterm survey helps instructors identify problems or frustrations in a class and make changes during the semester. signaling to students that their opinions and experiences matter. This in turn helps motivate students to complete end-of-semester surveys. Many instructors already administer midterm surveys either electronically (via Blackboard or other online tools) or with paper, asking students such things as what is going well in the class, what needs to change, and where they are struggling. This approach is backed up by research from a training-evaluation organization called ALPS Insights, which has found that students are more likely to complete later course surveys if instructors acknowledge and act on earlier feedback they have given. It’s too late to adopt that approach this semester, but it is worth trying in future semesters.

Remember the limitations

Student surveys of teaching can provide valuable feedback that helps instructors make adjustments in future semesters. Instructors we spoke to, though, overwhelmingly said that student comments were the most valuable component of the surveys. Those comments point to specific areas where students have concerns or where a course is working well.

Unfortunately, surveys of teaching have been grossly misused as an objective measure of an instructor’s effectiveness. A growing body of research has found that the surveys do not evaluate the quality of instruction in a class and do not correlate with student learning. They are best used as one component of a much larger array of evidence. The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences has developed a broader framework, and CTE has created an approach we call Benchmarks for Teaching Effectiveness. It uses a rubric to help shape a more thorough, fairer and nuanced evaluation process.

Universities across the country are rethinking their approach to evaluating teaching, and the work of CTE and the College are at the forefront of that. Even those broader approaches require input from students, though. So as you move into your final classes, remind students of the importance of their participation in the process.

(What have you found effective? If you have found other ways of increasing student participation in end-of-semester teaching surveys, let us know so we can share your ideas with colleagues.)

The ‘right’ way to take notes isn’t clear cut

A new study on note-taking muddies what many instructors saw as a clear advantage of pen and paper.

The study replicates a 2014 study that has been used as evidence for banning laptop computers in class and having students take notes by hand. The new study found little difference except for what it called a “small (insignificant)” advantage in recall of factual information for those taking handwritten notes.

Daniel Oppenheimer, a Carnegie Mellon professor who is a co-author of the new paper, told The Chronicle of Higher Education:

“The right way to look at these findings, both the original findings and these new findings, is not that longhand is better than laptops for note-taking, but rather that longhand note-taking is different from laptop note-taking.”

A former KU dean worries about perceptions of elitism

Kim Wilcox, a former KU dean of liberal arts and sciences, argues in Edsource that the recent college admissions scandal leaves the inaccurate impression that only elite colleges matter and that the admissions process can’t be trusted.

“Those elite universities do not represent the broad reality in America,” writes Wilcox, who is the chancellor of the University of California, Riverside. He was KU’s dean of liberal arts and sciences from 2002 to 2005.

He speaks from experience. UC Riverside has been a national leader in increasing graduation rates, especially among low-income students and those from underrepresented minority groups. Wilcox himself was a first-generation college student.

He says that the scandal came about in part by “reliance on a set of outdated measures of collegiate quality; measures that focus on institutional wealth and student rejection rates as indicators of educational excellence.”

Wilcox was chair of speech-language-hearing at KU for 10 years and was president and CEO of the Kansas Board of Regents from 1999 to 2002.

Join our Celebration of Teaching

CTE’s annual Celebration of Teaching will take place Friday at 3 p.m. at the Beren Petroleum Center in Slawson Hall. More than 50 posters will be on display from instructors who have transformed their courses through the Curriculum Innovation Program, C21, Diversity Scholars, and Best Practices Institute. It’s a great chance to pick up teaching tips from colleagues and to learn more about the great work being done across campus.

Drawing inspiration from the stories of innovative teaching

By Doug Ward

Higher education has many stories to tell.

Finding the right story has been difficult, though, as public colleges and universities have struggled with decreased funding, increasing competition for students, criticism about rising tuition, skepticism from employers and politicians about the relevance of courses and degrees, and even claims that the internet has made college irrelevant.

One top of that, students increasingly see higher education as transactional. Colleges and universities have long lived on a promise that time, effort and learning will propel students to a better life and the nation to a more capable citizenry. Today, though, students and their parents talk about return on investment. They want to know what they are getting for their money, what sort of job awaits and at what salary.

All of this has put higher education on the defensive, searching for a narrative for many different audiences. The Association of American Colleges and Universities has focused its last two annual meetings on telling the story of higher education. I led a workshop and later a webinar on that topic, and participants were eager to learn from each other about strategies for making a case for higher education. At one of this year’s sessions, a workshop leader asked participants whether their universities were telling the story of education well.

No one raised a hand.

All too often, universities use their color brochures and websites to explain how prestigious they are and to sell students on an ivory tower fantasy. Both of those things have a place. By focusing on education as a product, though, they overlook what college is really about: challenges, disappointments, maturity, opportunity, growth, and, above all, learning.

Teaching and learning rarely make their way into the stories that universities tell. If they did, here are some of the things students would learn about:

- Kim Warren, associate professor of history, who has rethought the language she uses in her classes. In helping students think like historians, she treats everyone as English-language learners so that no one leaves class confused by terminology or expectations.

- Prajna Dhar, associate professor of engineering, who has made sure that students with disabilities can participate in the active learning at the heart of her classes.

- Mark Mort, who has transformed once-staid 100-level biology classes into vibrant hubs of activity where students help one another learn.

- John Kennedy, associate professor of political science, who draws upon his expertise in international relations to help students work through negotiation scenarios that diplomats and secretaries of state struggle with.

- Matt Smith, a GTA in geography, who has created an interactive sandbox that allows students to create terrain and use virtual rain to explore how water flows, collects and erodes.

- Genelle Belmas, associate professor of journalism, who has created a “whack-a-judge” game to help students learn about media law and a gamification class that helps them learn about things like audience, interactivity, and creativity.

- Phil Drake, associate professor of English, who uses peer evaluation to help students improve their writing and to gain practice at giving feedback.

- M’Balia Thomas, assistant professor of education, who uses Harry Potter books to demonstrate to TESOL and ELL teachers how they can use students’ existing knowledge to motivate them and to learn new material.

- Ward Lyles, assistant professor of urban planning, who passionately embraces team-based learning and who helps students learn to approach statistics with diversity, equity and inclusion in mind.

- Lisa Sharpe Elles, assistant teaching professor in chemistry, who has increased the use of open-ended questions in large chemistry classes by using artificial intelligence for grading.

- Sarah Gross, assistant professor of visual art, who uses self-assessment as a means for students to improve their pottery skills and to learn from peers.

I could go on and on. The stories of innovative techniques and inspirational approaches to teaching and learning at KU seem limitless. All too often, though, they go untold. That’s a shame because they are perhaps the most important stories that students and prospective students need to hear as they make decisions about college and college classes.

The stories we tell remind us of who we are and where we are going. One of our roles at CTE is to tell the stories of the inspiring teachers who form the heart of learning at KU. Another is to bring those teachers together in ways that allow them to inspire and learn from one another.

Great teaching is crucial to the future of higher education. It takes time, creativity, and passion. It is important intellectual work that deserves to be celebrated and rewarded.

That’s a story worth telling.

Reports point to the need for rethinking higher ed. But will we?

By Doug Ward

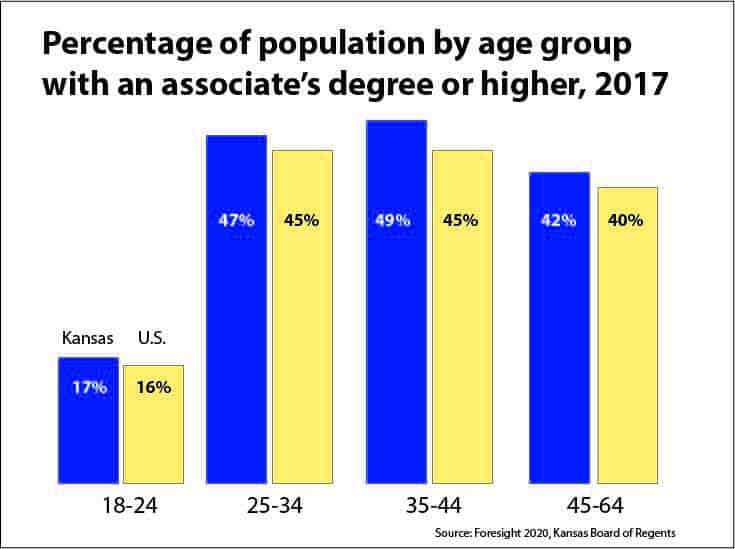

This year’s update on the Kansas Board of Regents strategic plan points to some difficult challenges that the state’s public colleges and universities face in the coming years.

First, the number of graduates is thousands short of what the regents say employers need each year. The number of certificates and degrees among public and private institutions actually declined by 1.2 percent between 2014 and 2018, and was 16 percent short of the regents’ goal.

I’ve written before about the shrinking pool of traditional students in coming years amid changing social norms. Full-time undergraduate enrollment nationwide peaked in 2010 and has been flat or declining since then. And as long as the economy remains stable, universities are likely to have trouble attracting older students. Since 2010, the number of Kansans between the ages of 25 and 64 who are taking classes at regents institutions has declined 20.4 percent. That decline is even steeper among those 35 and older.

Most certainly, the regents’ report highlights successes. For instance, the number of engineering graduates has already surpassed the regents’ goal for 2021. The regents president and chief executive, Blake Flanders, also writes that the state’s public colleges and universities have made transfer among institutions easier and that most bachelor’s degrees now require 120 hours of credit.

The primary goal of the strategic plan is to increase the number of post-secondary credentials among Kansans as a means to improve the state’s economy. This includes associate’s degrees and certificates in various technical fields. KU would have to increase its number of graduates 25% over the next two years to meet the regents’ goal. That’s a Sisyphean task, given recent trends.

KU has certainly made progress toward retaining students and helping them graduate. This has involved such things as transforming classes to make them student-centered, streamlining core classes, improving advising, making better use of data, adding freshman courses with fewer students, and adopting a host of other strategies.

The need for a clearer path for students

Disciplines within liberal arts and sciences have also worked at providing a clearer roadmap for students, often taking on some of the strategies of professional schools. Earlier this month, Paula Heron, a physics professor at the University of Washington, spoke to physics faculty at KU about the findings of a report called Phys21, which she helped write. That report urges physics departments to look more practically at the value of a physics degree.

Physics, like so many disciplines, is set up primarily to move students toward graduate school and academic careers, Heron said. Most students, though, don’t want to stay in academia. Forty percent of physics students go directly into the workforce and 61% work in the private sector, she said. Among physics Ph.D.s, only 35% work in academia.

Heron urged faculty to “educate people in physics so they have a broader sense of the world.” Help students apply their skills to practical problems. Give them more practice in writing, speaking, researching, and working in teams. Help students and career counselors understand what physics graduates can do.

One of the biggest challenges is that most physics professors lack an understanding of the job market for their graduates. They have worked in academia most of their lives and don’t have connections to business and industry, making it hard for them to advise students on careers or to help them apply skills in ways that will prepare them for jobs.

The challenge in physics mirrors that of many other disciplines. Academic work tends to focus our attention deeper inside academia even as demographic, social and cultural trends require us to look outward. If we are to thrive in the future, we must shift our perceptions of what higher education is and can be. That means transforming courses in student-centered ways and rewarding research and creative work that informs our teaching and brings new ideas and new connections to the classroom. That doesn’t mean we must throw out everything and start over. Not at all. We must be flexible and open-minded about teaching and research, though. Ernest Boyer made a similar plea in 1990 in Scholarship Reconsidered, writing:

“Research and publication have become the primary means by which most professors achieve academic status, and yet many academics are, in fact, drawn to the profession precisely because of their love for teaching or for service – even for making the world a better place. Yet these professional obligations do not get the recognition they deserve, and what we have, on many campuses, is a climate that restricts creativity rather than sustains it.”

Much has changed in the nearly 30 years since Boyer’s seminal work. Unfortunately, universities continue to diminish the value of teaching and service and creativity even as their future depends on creative solutions to attracting and teaching undergraduates. We have ample evidence about what helps students learn, what helps them remain in college, and what helps them move toward graduation. What we lack is an institutional will to reward those who take on those tasks. Until we do, we will simply be pushing the enrollment boulder up a hill again and again.

More from the report

A few other things from the regents report stand out:

- Only Fort Hays State met the regents’ goal for the number of graduates and certificate recipients in 2018, and it actually exceeded that goal by 3 percent. KU fell short by 14.3 percent, and K-State fell short by 10.7 percent. Community colleges and technical colleges were 11.9 percent short of the 2018 goal.

- A third of students attending regents institutions received Pell Grants in the 2017-18 academic year, slightly above the national average. Between 2014 and 2018, though, the number of students receiving Pell grants declined by 7 percent at Kansas’ public universities.

- Pell grants, which in 1998-99 covered 92 percent of the tuition for a student at a public university, now cover only 60 percent.

- The number of Hispanic students continues to grow, with Hispanics now accounting for 11.1% of students at regents institutions, compared with 7.6% in 2010. Enrollment among blacks has been steady at 7.4% of the student population. That is up from 6.3% in 2010 but down from 8.1% in 2013.

- Another metric the regents created, a Student Success Index, seems cause for concern. That index accounts for such things as retention and graduation rates among students who transferred to other institutions. Among all categories – state universities, municipal university, community colleges and technical colleges – students performed worse in 2017 than they did in 2010.

Does the U.S. have too many college graduates?

Here’s a view that runs counter to the Kansas regents’ argument that public universities need to increase the number of graduates. It comes from Richard Vedder, an emeritus professor at Ohio University, who argues in a Forbes article and a forthcoming book that universities are producing too many graduates. His claim: “We are over-invested in higher education.”

Vedder argues that colleges and universities face a triple crisis: The cost of college is too high; students are spending less and less time on academic work; and there is a disconnect between what universities teach and what employers want.

I agree with all of those things, though I disagree with the idea that we have too many college graduates. Vedder seems to approach education in strictly utilitarian terms, with graduates fitting like cogs in the machinery of capitalism. If all universities did was match course offerings to job requirements, they would deprive students of the broader skills they need to carve out meaningful careers and the broader ability to make innovative connections among seemingly disparate areas. They would also deprive the nation of citizens who can dissect complex problems and cut through the obfuscation that permeates our political system.

Briefly …

Enrollment challenges are hardly limited to the U.S. In the U.K., regulators say universities are overestimating the number of international students they expect to attract in the coming years, The Guardian reports. That is significant because the traditional-age student population is expected to decline in coming years in the U.K., and universities are looking overseas to attract students. … Research done by makers of educational products often greatly overestimates the effectiveness of those products, a Johns Hopkins University study warns. Product makers often create their own measurement standards, exclude students who fail to complete a protocol, or dismiss failures as “pilot studies,” according to The Hechinger Report. That leads to inflated results that the study calls the “developer effect.” In many cases, companies obscure the funding source of their studies.

Admissions scandal shines a harsh light on the ‘product’ of higher ed

We can glean many lessons from the most recent college admissions scandal.

A system that purports to be merit-based really isn’t. Standardized testing can be gamed. A few elite universities hold enormous sway in the American imagination. Hard work matters less than the ability to write a big check. The wealthy will do anything to preserve the privilege of plutocracy.

We knew all that, though.

What struck me most about the admissions scandal was how blatantly transactional a college degree has become and how vulnerable universities have become to sacrificing their integrity to the promise of a bigger donation.

I’ve written before about how the product of education – a diploma, an overemphasis on sports, bucolic images of campuses, perceptions of privilege from association with a particular institution – have overshadowed the process of learning. The admissions scandal not only reinforces that idea of education as a product but makes it clear that to many, education is only a product.

Those of us who teach see that mentality all too often in our classes. An undergraduate once told me that I was diminishing her prospects because she had to work too hard to earn an A. She knew what she wanted to do, she said, and she would learn nothing from my class or the other classes she was required to take. A degree with a high GPA was the only important thing, she said. Another student quoted his father as saying that the only thing college was good for was to meet people who could help you later.

Those students represent extremes of what higher education has become. College costs loom so large that students choose majors based on how much money they can make rather than on what might fulfill them in career. State governments perpetuate this by channeling money to favored programs rather than to universities as a whole, emphasizing economic development over an informed citizenry. The federal government encourages it by favoring privately issued college loans over grants and highlighting graduates’ income in comparing college programs. And universities themselves perpetuate it by chasing the status of rankings and promoting prestige over the needs of student learners.

Universities must live within this transactional culture but they must not sacrifice their integrity. They must address student concerns about costs and careers and salaries. They must make classes more accessible and convenient to students (see below). They must find fairer ways than standardized tests to gauge student competency.

Above all, they must promote the process rather than the product of education. A college education is certainly about career preparation, and institutions must help guide anxious students toward meaningful careers. They must also remind students that education is about learning and discovery. It’s about challenging ideas and beliefs, about challenging the self. It’s about a wide range of values and intellectual challenges that must be lived and earned, not bought and sold.

If nothing else, the admissions scandal should push universities to take a hard look at themselves and ask what they value, how they are perceived, and how they can maintain their integrity. If they don’t, they risk becoming just a wall decoration in a tarnished gilded frame.

Experimenting with new models of higher education

MOOC-mania has largely subsided, but companies and non-profit organizations continue to experiment with models that allow students to take online courses at little or no cost and transfer the credits to traditional colleges and universities.

EducationNext writes about three of those entities – StraighterLine, Modern States, and Global Freshman Academy – which collectively have enrolled more than 500,000 students but have mostly had the same low completion rates as MOOCs.

For instance, Arizona State created Global Freshman Academy in 2015. That program allows students to take 14 online freshman-level courses for $600 each. Of 373,000 who have enrolled, only 1,750 have completed. Students who have enrolled in classes through StraighterLine and Modern States generally complete only a course or two.

Those are hardly stunning results, but they are nonetheless worth watching. Many students are already acquiring college credit(link unavailable) through advanced placement exams and dual-enrollment courses, which are generally taught on college campuses. KU is also expanding the number of classes it offers through Lawrence Public Schools, with courses created by KU instructors but taught by high school teachers. Students will pay a lower rate for those courses.

The Edwards Campus has taken this even further, working with area high schools and community colleges so that students can earn a college degree in three years.

Take a trip on the K-10 bus between Lawrence and Johnson County Community College, and you will see substantial numbers of KU students traveling to classes at JCCC. Many others take online community college classes in the summer, not only because of the convenience but because of the lower cost. Some university classes incorporate MOOCs in their instruction, supplementing the online materials with in-class discussions and problem-solving.

The upshot of all this is that a college education is not always centered on a single institution. Most universities treat it that way, but students are increasingly considering cost and convienience. And as long as the cost of a college education pushes large numbers of students into debt and the demand for flexibility in scheduling and class format grows, there will be opportunities for outside organizations to step in with alternative approaches to higher education.

Perception and reality of university budgets

Those of us in higher education know all too well that states have slashed funding for colleges and universities over the last 10 years.

Yes, “slashed” is the right work. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities says that states’ spending on higher education is $9 billion lower today than it was in 2008, after adjusting for inflation.

That message apparently hasn’t gotten through to the American public, though.

According to a poll conducted by APM Research Lab and the Hechinger Report (Link Unavailable), 34% of Americans think funding for higher education has stayed the same over the last 10 years, and 27 percent think it has increased. (We wish.) Only 29 percent realize that funding has actually declined.

More people realize that government-financed grants and loans have not kept up with tuition increases. In the APM-Hechinger poll, 44 percent said they knew that. Disturbingly, though, about the same percentage said they thought that government aid had either increased or stayed the same.

The poll showed some interesting disparities among various groups. I won’t go into those other than to say that Easterners seem better informed than Westerners and Democrats better informed than Republicans. The abysmal overall understanding, though, should send a clear message to those of us who work in higher education: We need to do a better job of communicating with the public.

Briefly …

EdSurge asks an intriguing question – Is creativity a skill? – and then seeks answers from the perspective of various professions. … The University of Missouri plans to add five new undergraduate degrees and four new graduate degrees as part of its plan to increase enrollment by 25,000 students by 2023, The Missourian reports. … From the this sounds familiar department, a committee in the Missouri House of Representatives is considering a bill that would allow concealed carry of firearms on public university campuses. … Moody’s has issued a new warning about the finances of universities as enrollment flattens or declines, Education Dive reports. … Speaking of finances, Blackboard has agreed to sell one of its businesses and plans to move its headquarters outside Washington, D.C., as part of an effort to reduce its substantial debt, an analyst writes in e-Literate. …

Negotiating the challenges of a new approach to evaluating teaching

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – Faculty members seem ready for a more substantive approach to evaluating teaching, but …

It’s that “but” that about 30 faculty members from four research universities focused on at a mini-conference here this week. All are part of a project called TEval, which is working to develop a richer model of teaching evaluation by helping departments change their teaching culture. The project, funded by a $2.8 million National Science Foundation grant, involves faculty members from KU, Colorado, Massachusetts, and Michigan State.

The evaluation of teaching has long centered on student surveys, which are fraught with biases and emphasize the performance aspects of teaching over student learning. Their ease of administration and ability to produce a number that can be compared to a department average have made them popular with university administrators and instructors alike. Those numbers certainly offer a tidy package that is delivered semester to semester with little or no time required of the instructor. And though the student voice needs to be a part of the evaluation process, only 50 to 60 percent of KU students complete the surveys. More importantly, the surveys fail to capture the intellectual work and complexity involved in high-quality teaching, something that more and more universities have begun to recognize

The TEval project is working with partner departments to revamp that entrenched process. Doing so, though, requires additional time, work and thought. It requires instructors to document the important elements of their teaching – elements that have often been taken for granted — to reflect on that work in meaningful ways, and to produce a plan for improvement. It requires evaluation committees to invest time in learning about instructors, courses and curricula, and to work through portfolios rather than reducing teaching to a single number and a single class visit, a process that tends to clump everyone together into a meaningless above-average heap.

That’s the where the “but …” comes into play. Teaching has long been a second-class citizen in the rewards system of research universities, leading many instructors and administrators to chafe at the idea of spending more time documenting and evaluating teaching. As with so many aspects of university life, though, real change can come about only if we are willing to put in the time and effort to make it happen.

None of this is easy. At all the campuses involved in the TEval project, though, instructors and department leaders have agreed to make the time. The goal is to refine the evaluation process, share trials and experiences, create a palette of best practices, and find pathways that others can follow.

At the meeting here in Charlotte, participants talked about the many challenges that lie ahead:

- University policies that fail to reward teaching, innovation, or efforts to change culture.

- An evaluation system based on volume: number of students taught, numbers on student surveys, number of teaching awards.

- Recalcitrant faculty who resist changing a system that has long rewarded selfishness and who show no interest in reframing teaching as a shared endeavor.

- Administrators who refuse to give faculty the time they need to engage in a more effective evaluation system.

- Tension between treating evaluations as formative (a means of improving teaching) and evaluative (a means of determining merit raises and promotions).

- Agreeing on what constitutes evidence of high-quality teaching.

Finding ways to move forward

By the end of the meeting, though, a hopeful spirit seemed to emerge as cross-campus conversations led to ideas for moving the process forward:

- Tapping into the desire that most faculty have for seeing their students succeed.

- Working with small groups to build momentum in many departments.

- Creating a flexible system that can apply to many circumstances and can accommodate many types of evidence. This is especially important amid rapidly changing demands on and expectations for colleges and universities.

- Helping faculty members demonstrate the success of evidence-based practices even when students resist.

- Allowing truly innovative and highly effective instructors to stand out and allowing departments to focus on the types of skills they need instructors to have in different types of classes.

- Allowing instructors, departments and universities to tell a richer, more compelling story about the value of teaching and learning.

Those involved were realistic, though. They recognized that they have much work ahead as they make small changes they hope will lead to more significant cultural changes. They recognized the value of a network of colleagues willing to share ideas, to offer support and resources, and to share the burden of a daunting task. And they recognized that they are on the forefront of a long-needed revolution in the way teaching is evaluated and valued at research universities.

If we truly value good teaching, it must be rewarded in the same way that research is rewarded. That would go a long way toward the project’s ultimate goal: a university system in which innovative instructors create rich environments where all their students can learn. It’s a goal well worth fighting for, even if the most prevalent response is “but …”

A note about the project

At KU, the project for creating a richer system for evaluating teaching is known as Benchmarks for Teaching Effectiveness. Nine departments are now involved in the project: African and African-American Studies; Biology; Chemical and Petroleum Engineering; French, Francophone and Italian; Linguistics; Philosophy; Physics; Public Affairs and Administration; and Sociology. Representatives from those departments who attended the Charlotte meeting were Chris Fischer, Bruce Hayes, Tracey LaPierre, Ward Lyles, and Rob Ward. The leaders of the KU project, Andrea Greenhoot, Meagan Patterson and Doug Ward, also attended.

Briefly …

Tom Deans, an English professor at the University of Connecticut, challenges faculty to reduce the length of their syllabuses, saying that “the typical syllabus has now become a too-long list of policies, learning outcomes, grading formulas, defensive maneuvers, recommendations, cautions, and referrals.” He says a syllabus should be no more than two pages. … British universities are receiving record numbers of applications from students from China and Hong Kong, The Guardian reports. In the U.S., applications from Chinese students have held steady, but fewer international students are applying to U.S. universities, the Council of Graduate Studies reports. … As the popularity of computer science has grown, students at many universities are having trouble getting the classes they need, The New York Times reports.

Academia’s increasingly difficult balancing act

By Doug Ward

Education has always been a balancing act. In our classes, we constantly choose what concepts to emphasize, what content to cover, what ideas to discuss, and what skills to practice. As I wrote last week, the choices we make will influence our students throughout their careers.

Higher education is now facing a different kind of balancing act, though, one that involves not just what we teach and who we are but what college is and should be about and how it fits into the broader fabric of society. The recent annual meeting of the Association of American Colleges and Universities made clear just how tenuous a grasp higher education has on credibility and how broad the gap is between internal and external perceptions of colleges and universities.

Consider this from Brandon Busteed, a former Gallup executive who is now president of Kaplan University Partners:

“If you were to take the most brilliant marketing minds in the world, put them in a room for a day, lock them in there and say, please emerge with words that would be the worst possible combination to use in attracting students to higher education, they would emerge with one combination called ‘liberal arts.’ ”

Ouch!

To explain that, he referred to a study of high-performing, low-income students at Stanford. When asked what they thought of liberal arts, they most commonly replied: “What’s that?” Or “I’m not liberal.” Or “I’m not good at or interested in art.”

Lest those of you in professional programs start to feel smug, read on.

The negative connotations of ‘college’

In Gallup polling, Busteed said, Americans express confidence in “higher education” and “post-secondary education.” They see those things as important to the future. When asked about “college” or “university,” though, the warm feelings suddenly chill.

“Why?” Busteed asked. “When we say ‘college,’ we think about traditional-age students. We think about a residential experience. We think about Animal House movies.”

In other words, Americans see a need for education to prepare them for jobs and careers. Increasingly, though, the typical student who needs additional education looks nothing like Flounder, Babs or Bluto and wants nothing to do with a system they see as driven by liberal ideology and populated by drunken misfits more interested in toga parties than in preparing for the future.

“The words are holding us back,” Busteed said.

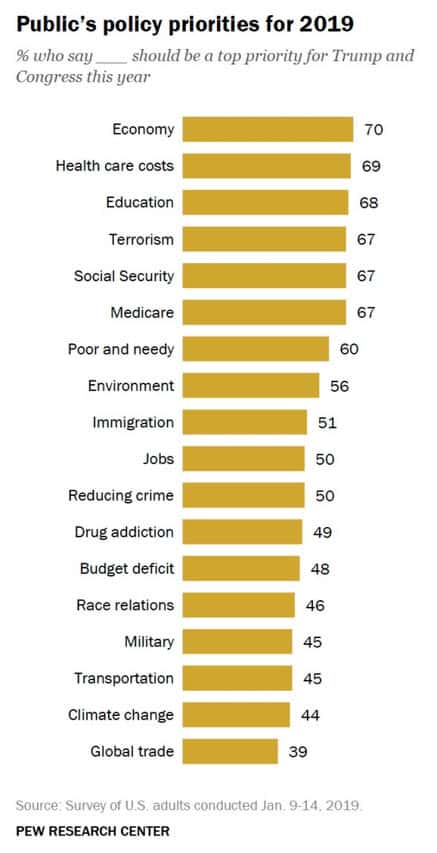

A new study from the Pew Research Center reinforces that. According to Pew, Democrats rank improving education as the second most important priority for the president and Congress, trailing only reducing health-care costs. Republicans, on the other hand, see defending against terrorist attacks, fixing social security and dealing with immigration as far more important than education or health care.

Another divide shows up in the Pew survey, with about three-quarters of women and those between 18 and 49 years old saying that improving education should be the top priority. Men and older Americans see education as a less pressing issue. The Pew poll doesn’t distinguish K-12 from higher education, but it does point to the complicated relationship Americans have with education of all sorts today. And the way educators see education and the way the public sees education are vastly different.

“Talk of higher education as a public good, of investing in societal education, has been replaced by talk of return on investment: tuition in exchange for jobs,” Lynn Pasquerella, president of AAC&U said during the organization’s annual meeting. She added: “The fact that Americans believe more in higher education than in colleges and universities is a clear indication that the way we talk about what we do in academia shapes public perception.”

Employers’ conflicted feelings

That perception applies not only to the public whose voices carry weight in state and federal funding of education but to the businesses and organizations that hire college graduates.

A survey AAC&U conducted last year found that only 63% of business executives and hiring managers have a great deal or quite a lot of confidence in colleges and universities. That’s higher than the 45% of the public who express confidence in colleges and universities. And if you ask those same business leaders whether college is worth the time and expense, 85% to 88% say yes, according to the AAC&U survey.

The responses indicate a clear ambivalence about higher education, though. Nearly all of the business leaders say they are asking employees to take on more responsibilities and more complex tasks than in the past. Nearly all of them say they are looking for prospective employees who think critically and communicate clearly, possess intellectual and interpersonal skills that will lead to innovative thinking, and have an ability to use a broader range of skills than workers in past years did. Many of them just aren’t convinced that college is preparing students for that.

Many academics will scoff at the focus on business leaders. A university education isn’t the same as job training, they say. It isn’t about tailoring classes to meet the specific demands of the business world and molding students into corporate clones.

I agree. And yet as the cost of college has risen precipitously, students increasingly want assurances that their degrees will lead to good jobs. We can – and should – talk about how our degrees will make students into better people and better citizens, about how our courses prepare students to face the unpredictable challenges of the future. Students want that, too. Above all, though, they want to be able to pay off their loans once they graduate. As Busteed told the AAC&U gathering, today’s students, as “consumers of higher education,” want more efficient and less expensive paths through college, and they want their coursework aligned with the jobs they will take upon graduation.

So we are back to the balancing act that those of us inside colleges and universities face. We want our students to leave with disciplinary knowledge but must help them understand how our disciplines lead to careers. We fret over week-to-week understanding of course material even though much of it is very likely to be obsolete within a few years. We try to teach in a reasoned, meaningful, inclusive way even as a partisan, skeptical public questions our epistemological foundations. We carry the burden of a name – college or university – that has lost its cachet even as a wary and reluctant public continues to see a need for what we do.

What’s the point of a major?

A colleague at AAC&U pointed to an enormous paradox in teaching and learning today. As students flood into what they see as “safe” majors of business and engineering, the liberal arts and sciences have donned the mantle of job skills. English isn’t just about literature and poetry; it’s about the communication skills that employers prize. History isn’t just about an understanding of the past; it’s about critical thinking skills that will get you a job. Political science isn’t just about the machinations of government; it’s about learning to work in groups so you can thrive in a career.

All of those things are true, but as my colleague reminded me, students don’t choose a major because they think it will make them better at group work, improve their critical analysis, or allow them to make better decisions independently. They choose a major because they are passionate about literature or linguistics or biology or politics or French or journalism or (name the major).

So more than ever, we educators must approach our work in multiple layers. We must balance disciplinary depth with broad-scale career skills, short-term understanding with long-term viability. We must learn to explain our majors more meaningfully and our roles as academics more thoughtfully. We must help our students explore the many facets of our majors while helping them connect to the ideas and philosophies of other majors. We must guide students through the details of disciplinary competency while recognizing that only the broader skills and experiences – what the media historian Claude Cookman calls the “residue” of education – generally sticks with students over the years.

Higher education has always been about exploration and understanding. As those of us who make up higher education balance the many demands pressing down on us today, though, we must undertake a broader exploration of just who we are because, increasingly, those on the outside don’t know.

What sort of future are we preparing our students for?

Those of us in higher education like to think of ourselves as preparing students for the future.

That’s a lofty goal with a heavy burden. Predicting the future is a fool’s game, and yet as educators we have accepted that responsibility by offering degrees that we tell our students will have relevance for years to come.

In our courses and with our colleagues, we simply don’t talk nearly enough about how we foresee the future and what role our disciplines will play. We have a responsibility to ask ourselves difficult questions: What skills will our students need not just next year, but in the next decade and the 40 or 50 years after that? What can we do to prepare students for a future we can’t possibly predict?

The core curriculum is certainly part of the answer, emphasizing such broad skills as critical thinking, quantitative reasoning, communication, ethics, creativity, and synthesis. Those show up frequently in the lists of skills for the future issued by various organizations and industries. Other skills I’ve seen listed recently on those lists include agility, resilience, flexibility, entrepreneurism, technological know-how, relationship building, systems thinking, global awareness, online collaboration, emotional intelligence, and an ability to spot trends. Groupings of those are sometimes referred to as “power skills.”

You can find many others. Most likely you have your own. Or you may prefer to think about higher education in broader terms, much as Bernard Bull, assistant vice president for academics at Concordia University Wisconsin, wrote about recently:

“The essence of a great college experience is not a college degree. It is a rich, engaging, empowering, enlightening and transformative learning experience. It is the experience of a network that may well extend through one’s lifetime. It is the experience of being immersed in a culture of curiosity and a love of learning. It is a place where you are stretched, challenged, inspired, and pushed to discover meaning and purpose in your life and the world around you.”

Most certainly, college helps students learn about themselves, their peers and society, develop independence and responsibility, and gain enough disciplinary understanding to apply skills in a meaningful (if often rudimentary) way. There’s a danger in being too general, though, because those generalizations make academia an easy target for critics, who like to paint higher education as out of touch and irrelevant. In that view, all a person needs is hard work, ingenuity and grit, not a college degree. Drawing on those inner skills is not only practical but much, much cheaper.

A variation on that theme posits that college students are ill-prepared for the jobs of today, let alone the jobs of tomorrow. You don’t have to look far to find scathing portrayals of universities as mindless playgrounds in which students dally for four (or five or six) years and emerge mired in debt and no more prepared to face the world than when they started college.

Both of those portrayals hold grains of truth, but they also view education through the lens of neo-liberal utilitarianism. In that view, the only valuable skill is one that leads to monetary gain and the only valuable graduates are those that fit like cogs into predetermined slots of corporate machinery. A degree, in that view, is all about the money. The federal government has backed that perspective by promoting comparisons of graduates’ salaries vs. cost of degree, and universities have perpetuated it themselves as they have whittled away at the liberal arts, raised tuition to levels that stretch ordinary families to the limit, and run themselves like corporations rather than nonprofits that serve the public good. States and the federal government have forced universities to adopt that way of thinking as they have slashed spending on higher education and turned student loans into a guaranteed profit center for private lenders.

There’s plenty of blame to go around.

It’s the beginning of the semester, though. Students and instructors have a chance to start anew. We can’t solve all the problems of higher education in a single semester, no more than we can teach students all the skills they need in a single class. We can and must keep the broader picture in mind, though, as we lead students into a new exploration of disciplinary challenges, societal problems, and academic inquiries. As we do, though, we must remember that knowledge is useless without an ability to apply it, and that skills have limited currency without an ability to refresh, revise and remake them.

So as you begin the semester, consider this: What are you doing to prepare your students for the future? And how will they know they are on the right track?

Worth considering …

“I think it is important for parents to be situated in the context of the digital revolution through which we are living. It was only 11 years ago that the iPhone was introduced, and faster download speeds, and it has transformed almost all of American community life. Inevitably, for good or for ill, it’s going to transform where education heads.”

—Sen. Ben Sasse, R-Nebraska, speaking at the ExcelinEd conference

Briefly …

The Midwest is producing an increasingly larger share of graduates in technology-related fields, the website OZY reports. Twenty-five percent of computer science graduates now come from the Midwest, OZY writes, saying that “tomorrow’s innovators may never set foot in Silicon Valley.” … The Atlantic looks at the struggle that the University of Wisconsin at Stevens Point faces in maintaining liberal arts programs amid budget cuts and a declining number of majors. … Providing students more direction and community could help reverse declining enrollments in history programs, Jason Steinhauer of Villanova argues in a Time column. … Politico writes about how free college, an idea usually associated with liberal politics, has been enthusiastically embraced in conservative Tennessee.

Engaging students through silent contemplation

Here’s another approach to using silence as a motivator for active learning.

I’ve written previously about how Genelle Belmas uses classroom silence to help students get into a “flow state” of concentration, creativity, and thinking. Kathryn Rhine, as associate professor of anthropology, uses silence in as part of an activity that challenges students to think through class material and exchange ideas but without speaking for more than 30 minutes.

Rhine calls this approach a silent seminar, and she explained it during demonstrations at a meeting of CTE’s C21 Consortium(Link Unavailable) earlier this month. The technique can be easily adapted for nearly any class and seems especially useful for helping students reflect on their learning at the end of the semester.

Here’s how Rhine uses the activity:

She covers four tables with butcher block paper and moves them to the corners of the room. She creates four questions about class readings and assigns one to each table. She used this recently after students read Ann Fadiman’s book When the Spirit Catches You Fall Down. Three of the questions were based on core themes of the book. The fourth asked students to consider elements of the book that were less resolved than others.

Each student receives a marker and is assigned to a group at one of the four tables. Students then consider the questions and write their responses on the butcher block paper.

“I tend not to tell them how to answer the question,” Rhine said. “I simply say just write or reflect or comment.”

They have five to eight minutes to write before moving to another table. They add their responses to the questions at the new table but also respond to answers that other students have written down.

As “silent seminar” suggests, this is all done without speaking. Once students have responded to all four questions, though, Rhine gives them permission to talk. And after 30 to 40 minutes of required silence, they are ready to discuss, she said.

Working in their groups, students summarize the core themes of the comments on the tables, nominating one person from each group to present their summaries to the class.

“If there’s still time remaining in the class, I will then have a conversation about what we saw and what was missing or surprising or contradictory,” Rhine said. “I want them to think about the patterns of reflection, not just what was reflected.”

She also asks students to reflect on the approach used in the silent seminar. How was it different from a typical class and how did it change the way they participated?

Rhine’s classes range from 10 to 30 students, but the silent seminar could be used in any size class. If a room doesn’t have tables, use whiteboards or attach paper to the walls and have students write in pen. Giant sticky notes would make this easy. I could see this working with digital whiteboards or discussion boards, as well.

The key to the exercise, as with all active learning, is student engagement. Rhine has found the silent seminar particularly effective in that regard.

“I like that this is more inclusive,” she said. “It allows students who are more silent in class or who are afraid to speak out the ability to write and reflect. I also like that students who have lots of things to say can put it down on paper.”

She has also found the anonymity of the exercise helpful. Students are more likely to take intellectual risks when they don’t have the entire class watching them and listening, she said.

The silent seminar also engages students in several different ways: critical thinking, writing, summarizing, and presenting.

It has an added benefit for the instructor.

“I love 40 minutes of silence where I can just rotate around and not have to be on the whole time,” Rhine said.

Another new tool from JSTOR

JSTOR Labs, the innovation arm of the academic database JSTOR, has released a new tool that allows researchers to find book chapters or journal articles that have cited specific passages from a primary document.

The tool, called Understanding Great Works, is limited to material in the JSTOR database. It is also limited to just a few primary sources: Shakespeare’s plays, the King James Bible and 10 works of British literature.

It works like this: You open a primary text on the JSTOR site. A list along the right side of the digital document shows how many articles or books have quoted a particular passage. Clicking on the number opens a pop-up box with the sources and a passage showing how the line was used in a particular article or book chapter.

Understanding Great Works expands on project called Understanding Shakespeare, which was released in 2015, and JSTOR Labs is asking for input on what primary texts should be added next. (Oscar Wilde’s play “The Importance of Being Earnest” had the most votes as of Thursday.) I learned about it from a post on beSpacific.

JSTOR Labs has been releasing a new digital tool about once a year. A tool called Text Analyzer, which was released last year, is worth checking out. It allows you to upload a document for analysis by JSTOR, which then offers suggestions for sources in the JSTOR database. It works not only with Word documents and PDFs but with PowerPoint, spreadsheets and even photos of documents.

* * * * * *