Here’s another approach to using silence as a motivator for active learning.

I’ve written previously about how Genelle Belmas uses classroom silence to help students get into a “flow state” of concentration, creativity, and thinking. Kathryn Rhine, as associate professor of anthropology, uses silence in as part of an activity that challenges students to think through class material and exchange ideas but without speaking for more than 30 minutes.

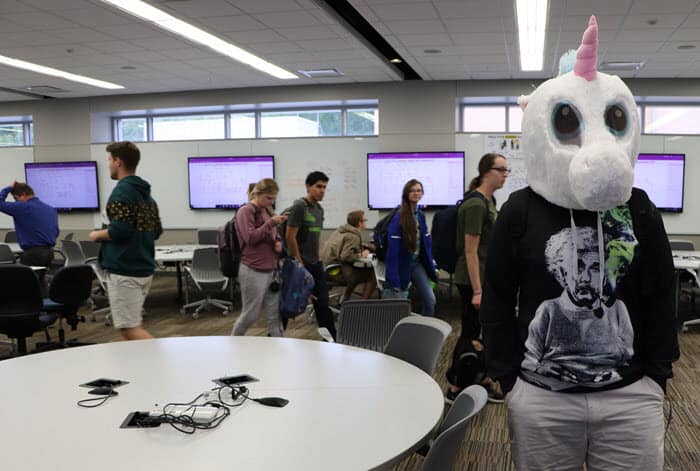

Rhine calls this approach a silent seminar, and she explained it during demonstrations at a meeting of CTE’s C21 Consortium(Link Unavailable) earlier this month. The technique can be easily adapted for nearly any class and seems especially useful for helping students reflect on their learning at the end of the semester.

Here’s how Rhine uses the activity:

She covers four tables with butcher block paper and moves them to the corners of the room. She creates four questions about class readings and assigns one to each table. She used this recently after students read Ann Fadiman’s book When the Spirit Catches You Fall Down. Three of the questions were based on core themes of the book. The fourth asked students to consider elements of the book that were less resolved than others.

Each student receives a marker and is assigned to a group at one of the four tables. Students then consider the questions and write their responses on the butcher block paper.

“I tend not to tell them how to answer the question,” Rhine said. “I simply say just write or reflect or comment.”

They have five to eight minutes to write before moving to another table. They add their responses to the questions at the new table but also respond to answers that other students have written down.

As “silent seminar” suggests, this is all done without speaking. Once students have responded to all four questions, though, Rhine gives them permission to talk. And after 30 to 40 minutes of required silence, they are ready to discuss, she said.

Working in their groups, students summarize the core themes of the comments on the tables, nominating one person from each group to present their summaries to the class.

“If there’s still time remaining in the class, I will then have a conversation about what we saw and what was missing or surprising or contradictory,” Rhine said. “I want them to think about the patterns of reflection, not just what was reflected.”

She also asks students to reflect on the approach used in the silent seminar. How was it different from a typical class and how did it change the way they participated?

Rhine’s classes range from 10 to 30 students, but the silent seminar could be used in any size class. If a room doesn’t have tables, use whiteboards or attach paper to the walls and have students write in pen. Giant sticky notes would make this easy. I could see this working with digital whiteboards or discussion boards, as well.

The key to the exercise, as with all active learning, is student engagement. Rhine has found the silent seminar particularly effective in that regard.

“I like that this is more inclusive,” she said. “It allows students who are more silent in class or who are afraid to speak out the ability to write and reflect. I also like that students who have lots of things to say can put it down on paper.”

She has also found the anonymity of the exercise helpful. Students are more likely to take intellectual risks when they don’t have the entire class watching them and listening, she said.

The silent seminar also engages students in several different ways: critical thinking, writing, summarizing, and presenting.

It has an added benefit for the instructor.

“I love 40 minutes of silence where I can just rotate around and not have to be on the whole time,” Rhine said.

Another new tool from JSTOR

JSTOR Labs, the innovation arm of the academic database JSTOR, has released a new tool that allows researchers to find book chapters or journal articles that have cited specific passages from a primary document.

The tool, called Understanding Great Works, is limited to material in the JSTOR database. It is also limited to just a few primary sources: Shakespeare’s plays, the King James Bible and 10 works of British literature.

It works like this: You open a primary text on the JSTOR site. A list along the right side of the digital document shows how many articles or books have quoted a particular passage. Clicking on the number opens a pop-up box with the sources and a passage showing how the line was used in a particular article or book chapter.

Understanding Great Works expands on project called Understanding Shakespeare, which was released in 2015, and JSTOR Labs is asking for input on what primary texts should be added next. (Oscar Wilde’s play “The Importance of Being Earnest” had the most votes as of Thursday.) I learned about it from a post on beSpacific.

JSTOR Labs has been releasing a new digital tool about once a year. A tool called Text Analyzer, which was released last year, is worth checking out. It allows you to upload a document for analysis by JSTOR, which then offers suggestions for sources in the JSTOR database. It works not only with Word documents and PDFs but with PowerPoint, spreadsheets and even photos of documents.

* * * * * *