How to approach class discussions when emotions run high

By Doug Ward

Strong beliefs about volatile issues can quickly turn class discussions tumultuous, especially during election season.

Rather than avoid those discussions, though, instructors should help students learn to work through them civilly and respectfully. That can be intimidating, especially in classes that don’t usually address volatile issues.

Jennifer Ng, director of academic inclusion and associate professor of educational leadership and policy studies, says transparency is the best way to proceed with those types of discussions. Be up front with students about how emotionally charged issues can be, she told participants at a CTE workshop on Friday. Explain what you are doing and why, but also be clear that you don’t know exactly where the conversation might go.

The CTE website offers advice on how to handle difficult discussions, KU Libraries lists many resources for helping students with media literacy, and Student Affairs lists resources where students, faculty and staff can turn for help in working through personal and professional issues.

Participants at Friday’s workshop shared many ideas on how to make class discussions go more smoothly. Here are a few:

Focus on facts. Politics has become increasingly polarized, making it easy for discussions to turn into heated rants. So help students focus on the facts of an issue or position. What do we know and how do we know it? What has scholarship suggested? Yes, the word “facts” has itself become problematic in a political atmosphere where partisans dismiss anything they don’t like and instead embrace “alternative facts.” Helping students identify what the facts are can help keep discussions away from personal attacks.

Challenge the position, not the person. That, of course, is an approach educators have advocated for years. If we hope to have civil discussions, we have to help students pick apart arguments rather than alienate people they disagree with.

Ask students to imagine an objective approach. Rather than taking a partisan side, ask students to step back and look at arguments from a neutral perspective. What are the strengths and weaknesses of each side? Ng describes this as having students look at the world in a ”meta” sort of way, one that moves them out of the fray and into a broader perspective.

Have students take an opposite view from their own. This is similar to the neutral viewpoint in that it forces students to step back from strongly held positions and consider why others might disagree. Have them write a paragraph explaining that other perspective so they can think through it more meaningfully. Another approach is to have students look at the issues from the perspective of an international student.

Have students create ground rules for discussions. This helps them feel invested in a conversation and reminds them of the importance of respectful discussions.

Have a “pause button.” This is a signal that any student can use to indicate that discussions are becoming too heated and need to stop, at least briefly. The pause can help everyone regroup so the conversation can remain civil.

Give students permission to check out of a conversation. Some instructors allow students to pick up their phones and block out a discussion if it gets too intense. This can also signal to an instructor that the conversation might need to pause. Some instructors allow students to leave the room if things get too heated, but that also draws attention to students who leave.

Don’t assume you have to know what to say. If something comes up that you aren’t prepared to deal with, explain to students that you need to do some research and will get back to them by email or during the next class. Sometimes, instructors just need to listen and try to understand rather than wading into a subject unprepared.

Have students do some writing before they leave class. This can help ease tension, but it also gives instructors a sense of what students are thinking and what they might need to address in a later class.

Take care of yourself. Instructors who deal with emotional classroom issues and listen to students’ personal challenges can suffer what the American Counseling Association calls vicarious trauma or compassion fatigue. This is tension brought on by dwelling on stories of traumatic experiences that others have shared. A recent article in Faculty Focus offers suggestions for dealing with these types of issues.

KU’s interim provost, Carl Lejuez, offered an excellent goal for all discussions at the university. In his weekly message to the campus this week, Lejuez wrote:

“There is no weakness in being respectful. There is no shame in being considerate. There is nothing wrong with a desire to be a community that cares for its people. Put another way, KU is at its best when we are civil, understanding and compassionate.”

Briefly …

Forthcoming webinars led by the university’s Technology Instruction and Engagement team will focus on using MediaHub and the Blackboard grade center. You will find a full list of workshops on this site. Past webinars are available on KU IT’s YouTube channel, and the team’s resource page, How to KU, offers help on Office 365, Sharepoint, and several Adobe applications. … The Library of Congress has created what it calls the National Screening Room, an archive of films that can be downloaded or watched online. … Edutopia offers strategies for remembering students’ names. … Wichita State’s Campus of Applied Sciences and Technology will pay provide a free education, relocation expenses for incoming students who live more than 75 miles away, and housing and cost-of-living stipends, according to Education Dive. The program, which is funded by the Wichita Community Foundation, is intended to address a shortage of skilled workers in aviation fields like sheet metal assembly and process mechanic painting. Students are guaranteed jobs after they graduate.

Exploring the landscape of teaching and learning with someone who has helped to shape it

By Doug Ward

From the trenches, the work to improve college teaching seems interminably slow.

Those of us at research universities devote time to our students at our own peril as colleagues who shrug off teaching and service in favor of research earn praise and promotion. When we point out deep flaws in a lecture-oriented system that promotes passive, shallow learning, we are too often told that such a system is the only way to educate large numbers of students. We seemingly write the same committee reports over and over, arguing that college teaching must move to a student-centered model; that a system established for educating a 19th-century industrial workforce must adapt to the needs of 21st-century students; that higher education’s rewards system must value teaching, learning, and service – not just research.

That’s my perception, at least. During my 15 years as a faculty member, I have seen many positive changes as the benefits of active and engaged learning have seeped into broader conversation and as the need to reform higher education has become part of a growing number of conversations. The largest barriers to change seem immovable, though – especially as we push against them day by day. It’s easy to get discouraged.

So when I heard Mary Huber speak about dramatic changes she had seen in teaching and learning over the last three decades, I wanted to hear more. That was in January 2017 at the annual meeting of the Association of American Colleges and Universities. I finally had that opportunity a few months later at a meeting of the Bay View Alliance, a consortium of research universities working to improve teaching and leadership in higher education.

I was hoping not only to get a broader perspective on higher education but to gain some reassurance that the work we do to improve undergraduate education matters. I wasn’t disappointed. I never am when I speak to Mary, who has played a crucial role in shaping discussions about teaching and learning over the past 30 years. I have gotten to know her over the past few years through our work in the BVA. She was a founding member of the organization and is now a senior scholar and a member of its leadership team. The insights and leadership she brings to the BVA were honed over many years of work at the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, among other organizations.

A key role at Carnegie

At Carnegie, she helped lay the foundation for a movement for better teaching that has blossomed over the last decade. As an anthropologist, she has studied colleges and universities as cultural institutions, offering insights into how they work and why they do what they do. She oversaw Carnegie’s role in the U.S. Professors of the Year Program for many years, directed the Cultures of Teaching and Learning Project and the Integrative Learning Project at Carnegie, and served on the leadership team of the Carnegie Academy for the Scholars. These projects led to books in 2002, 2004, 2005, and 2011.

At Carnegie, Mary Huber was among the “we” that Ernest L. Boyer refers to in the recommendations in an influential 1990 report, Scholarship Reconsidered. That publication took higher education to task for diminishing undergraduate teaching through a rewards structure skewed toward narrowly defined research. She was a co-author of a follow-up book, Scholarship Assessed: Evaluation of the Professorate, and was an early advocate for the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL). She has continued to publish works about SoTL and present conference papers on improving teaching and learning. She also serves as a contributing editor to Change magazine.

Mary covered a lot of territory during a 30-minute conversation on a shady balcony during a mild summer day in Boulder, Colo. She spoke about such things as the rise of pedagogical scholarship within disciplines; the way that education scholarship in the United States developed separately from a line of inquiry followed in the U.K., Canada, and Australia; and the role that teaching centers have played in promoting engaged learning.

“There’s much more conversation today, more places for that conversation, more resources out there that have burgeoned, really, in the past 20 to 25 years,” she said.

She also spoke of faculty members and administrators in terms of the learning they must do about teaching and learning and “remember what it’s like to be a novice in this area” like our students.

She didn’t downplay the challenges, though. In fact, at the end of our interview, she made it clear that those challenges were enormous.

“I don’t think it’s fair to just say that colleges and universities are failing,” she said. “I think society is failing. If they need higher education to do something different, which I think they do, we cannot any longer settle for the kind of education that we have been providing to most of our students. Those good jobs in the workforce and the life they supported are no longer viable for a growing number of college graduates. We need to do better by the students. But we aren’t going to be able to do that without broader social support.”

To understand how we go to that point, though, we have to go back to the 1960s, when Mary Huber completed her undergraduate work at Bucknell University. It’s from that starting point that she explains the changing landscape of teaching and learning through the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

A Q&A with Mary Huber

Mary Huber: My first exposure to teaching in higher education was at a liberal arts college in central Pennsylvania, Bucknell University, a fine liberal arts college. That was in the mid-1960s. So that’s my baseline. From there, I went on to experience with graduate schools, first with my former husband’s and then with my own. After that I began work as a researcher and writer on higher education, first as a research assistant in economics and public policy at Princeton University and then through my roles at the Carnegie Foundation. So it’s kind of been an unbroken chain of some exposure to teaching and learning in higher education at different kinds of institutions.

I think that higher education itself began to change as the proportion of students going on to college changed. That was something that began after World War II, but really took off in the mid to late ’60s. And it brought to colleges and universities a lot of people who weren’t prepared in the traditional sense, at the level that high schools used to prepare college-bound students. There were people going to college who might not have gone in earlier years. That was partly made possible by the growth of community colleges at that time, but many four-year colleges had also opened their doors and brought in new students.

This influx of new students created pockets of pedagogical innovation in the university. I’m thinking in particular about some of the new fields that emerged during that period like composition. Not that composition hadn’t been around, but as a separate field with an identity of its own, it started in the late ’60s and early ’70s, dealing with this issue of students who weren’t prepared for college writing. Composition scholars have persisted in doing excellent work on teaching and learning, with many thoughtful, committed people working to understand and address the problems student writers face in academic writing tasks. There were some other new fields that took off around that time, like ethnic studies and women’s studies, which had a pedagogical twist to their mission. Concerned about how traditional power structures were re-enacted in the classroom, scholars in these fields were trying to create more democratic classrooms that empowered students to move beyond all that. So there were several pockets where there was some very interesting pedagogical thinking going on.

But small groups of people were becoming pedagogically restless in some of the older and larger fields as well. Math was certainly a case in point, spurred by the math wars in the K-12 arena, by the arrival of calculators, and (of course) by high rates of attrition in developmental and advanced introductory mathematics classes.

So there were things happening here and there, but it was in pockets. And at some point it spread out. There’s a very interesting article on changes in STEM education policy from roughly the mid-1980s to the late 1990s by Elaine Seymour, who led a center for ethnography and evaluation research right here at the University of Colorado. Her history began with concerns about the pipeline for STEM careers. There weren’t enough people graduating and continuing on in STEM careers, especially not enough women or underrepresented minorities who were coming in and persisting in STEM. That spurred government agencies to support research to explore why that would be. And there was some finger-pointing at pedagogy. But it wasn’t just finger-pointing. It was based on research that was being done at the time on people who did leave STEM to go elsewhere in the university. That, I think, has been another continuing stream of attention to teaching and learning, but not so walled off from other parts of the university. STEM was a large and a growing area in higher education and there was money for research on pedagogical and curricular issues that involved people in mainstream disciplines and institutions making that part of their work. Indeed, by the 2000s, well-known research leaders, like Nobel-prize winning physicist Carl Wieman were lending their prestige and their intelligence and their networks to initiatives to improve STEM teaching in higher education.

Doug Ward: So here we’re talking about the ’90s? 2000s?

MH: Getting into the ’90s and ’00s. But certainly concern about pedagogical and curricular issues in STEM education predated that, going all the way back to Sputnik in the 1960s.

Emergence of a teaching commons

DW: So this surprises me because it sounds like many of the same conversations we are having today: that there’s a concern and certainly a lot of effort over the last 10 years. Why has it been so hard to get some of the changes through to help our students?

MH: Well let me back up just a little to say that I actually think there have been many changes in teaching and learning over the past several decades. Some of them grew out of changes in our fields themselves – especially some of the goals, the way people thought about what they wanted for undergraduates. My field is anthropology and I think anthropology, like many others, has had thinkers who had pedagogical interests, and departments that wanted students to begin to experience what it was like to produce knowledge as professionals do in the field. This was also the case, I think, in history. Yes it’s true that not everybody jumped on board for that. But nonetheless there has been a growing sense that there is just too much knowledge out there now, too much information, too easy to access in this period with the internet and the Word Wide Web. So that was another push that maybe we should be doing something else with undergraduate education than just focusing on mastering content. That’s another thread to add to pipeline and equity concerns. And I think there have been many others – for instance, attention to service and community engagement, not to mention gaining mastery over the new technological tools of the academic trade.

Indeed, if you trace them all out, I think, the picture that emerges is the growth of something that Pat Hutchings and I have called a teaching commons. There’s much more conversation, more places for that conversation today, more resources out there that have burgeoned, really, in the past 20 to 25 years. Disciplinary societies have developed new journals or beefed up old ones about teaching in their fields. There are panels on teaching and learning and curriculum now at meetings that didn’t used to be there. For a long time, it really was a kind of an invisible ground. The traditional forms of teaching – we’ve all experienced them, at Bucknell or wherever we went – but then that’s what shifted.

From private conversations to public discussions

DW: That’s interesting. The way you’re describing it is that there were a lot of private conversations about teaching but really not the public places to have those discussions or the resources to disseminate information.

MH: That’s right. Or to make it part of your life as a teacher. There’s a lovely book by the scholar Wayne Booth. He was a literary critic and scholar of rhetoric at the University of Chicago. He has a wonderful book called The Vocation of a Teacher, published in 1988, which was a collection of his essays and speeches on educational themes. And the resources he cites on how he himself learned to teach are from another era. Not the citations and references you’d expect to find today. There was a footnote listing books that “teach about teaching by force of example” and citing “an obscure little pamphlet” about discussion teaching, but mostly, he said, he learned about teaching through staff meetings and conversations with colleagues. ..There was very little in terms of a formal apparatus of research, or of major thought leaders in teaching and learning. It was very sporadic. I wrote about that back in 1998 or ’99 in an essay on disciplinary styles in the scholarship of teaching. That’s when I was getting into this myself and realizing that there was much more going on than I thought. And I used Wayne Booth’s book an example of the thin web of scholarship on teaching and learning that was common before. Of course, there were thoughtful people who were wise about these things and had given it enough thought to write about it, but they didn’t have much to back it up.

DW: I’m going to veer a little bit because this sort of ties in with an article that you’ve been working on about what is known about teaching for liberal learning. We talked before our interview about how different strands in the scholarship of teaching and learning evolved. Essentially, in the 1970s and 1980s, the British were saying we have a theoretical grounding to our efforts to improve teaching and learning and you Americans don’t. It’s interesting how this kind of practitioner research started to form. How are you seeing the differences?

MH: It is interesting. The way I see it – I’m sure there are others whose standpoint is different – the U.S. never had a very robust area of scholarly research on learning and teaching in higher education. A lot of our focus in our graduate schools of education was on K-12.

DW: Yes.

Different approaches in the U.S. and Europe

MH: For some reason that was not true in the U.K. and Europe. One particularly strong line of work on students’ approaches to and experience of learning was really jump-started by a Swedish research team in the mid 1970’s. That’s when they published their initial papers, presenting work on the experience of learning that was then picked up by colleagues in the U.K., Australia, and Canada. Of course you can trace this theme back a long way. But in the U.S. we didn’t have that strong or coherent an education research group. There have always been a few involved in studies of teaching and learning in higher education, but their work didn’t really shape or constrain what was going on as other groups became interested. This led to a rather diverse set of communities and literatures. The field of learning sciences wasn’t really focused on higher ed, but what they were discovering about memory, prior knowledge and other kinds of things were presented as universally applicable. That was one stream. The professional development people took some of that literature and tried to put it into a frame that would be accessible and helpful to teachers in higher education. And then you had this emergence of the scholarship of teaching and learning, which was a practitioner’s form of research and inquiry into teaching practice. And that was followed by the emergence DBER, which stands for disciplinary-based education research. This involved people in disciplinary fields like chemistry education research and physics education research who had higher education as the domain in which they were examining the ins and outs of STEM learning and teaching.

So you have these many different streams. And over recent years, there have been more and more occasions where people coming from one or the other of those communities can have access to and become aware of what’s going on in the others. For example, longstanding journals like Teaching Sociology or Teaching of Psychology, have been raising the bar on what counts as quality in writing about teaching and learning. It’s no longer enough to tell readers about your clever idea for teaching this topic or that one. We really need to be looking at how students are responding to this kind of pedagogy. So those journals upped the ante for what they would be willing to publish. Other journals in other fields have been more recently founded, and there are now several online journals for the scholarship of teaching and learning itself. More campuses, too, now have centers for teaching and learning that have been sponsoring faculty learning communities and improvement initiatives around issues of teaching and learning that bring people together from across the campus. All these developments have helped widen and deepen the teaching commons, as we have more occasions and more reasons to meet each other and learn about each other’s work.

DW: So I’m visualizing a lot of threads that have been coming together, and the way you’re describing it is that we have shifted from an anecdotal approach to a scholarly approach where there is some substance; there is some foundation. But then where does the criticism from the British fit in?

MH: They had, and continue to have, a relatively small community of researchers who have been building on each other’s work for 30 to 40 years, exploring students’ approaches to learning, among other themes. That’s where these ideas of deep, surface, and strategic approaches to study emerged. They have looked at how that plays out in the lecture format, in the Oxbridge tutorial, in the seminar – indeed, they’ve gone far beyond just that simple trichotomy, and have created a body of knowledge that is often regarded as foundational for new faculty in the U.K. to learn about, or for scholars of teaching and learning there to reference in designing their own inquiries.

In 2008 a group of researchers from the Higher Education Academy at Oxford did a review of the literature on the student learning experience in higher education. You can see that it’s a body of literature that has depth and subtlety and people who are in communication with each other over the years, and that it’s benefited from a long history of exchange between researchers in Australia, Canada, and the U.K. They are a group of people whose careers shift continents and who stay in touch. That is very different from what we have. Very different.

So when the scholarship of teaching and learning caught on in the U.S. among people who are primarily teachers and researchers in their own disciplines – historians, mathematicians, whatever you have – it was both limited and empowered by the relative absence of a thriving local community of researchers in higher education pedagogy. As the scholarship of teaching and learning developed in the part of the world I was working from, at the Carnegie Foundation, we basically urged newcomers: ‘Come on. Draw on whatever you can. You don’t have to master the field of educational psychology or statistics or 40 years of research on this or that educational theme in order to be observant and reflective about what’s happening in your classrooms with your students. If you want to draw on Husserl(Link unavailable) or Heidegger, be my guest. There are many different ways in which insights from across the academic spectrum can inform your work.’ And I’m very glad. Some of us who were organizing this movement in the U.S. soon learned that your “typical” professor of Chaucer and medieval English literature may not have the time or the interest to tap a whole new (to them) area of study, although they certainly would be interested in addressing questions about their students’ learning. I myself, coming from the humanistic side of anthropology, had trouble with the literature in educational psychology and professional development. I wasn’t interested in it at first. I wasn’t sure about the epistemological grounds on which it was done. I didn’t have the expertise to read it with understanding. But that didn’t mean I wasn’t interested in student learning and couldn’t bring to it some thoughts and methods from my own field. Still, once people like me or that Chaucerian scholar come together around questions of learning with people from a variety of other fields, we soon expand our range of reference, and get better at accessing even the literature in education without being intimidated or offput.

Improving conversations about teaching

DW: I want to ask one more thing. What do you see as the biggest challenges right now in terms of teaching and learning?

MH: Well, I really would go along with the Bay View Alliance on that. I still think that building a stronger, more sophisticated conversation about teaching and learning in departments and disciplines and institutions – building stronger cultures of teaching and learning makes this a better conversation, one people are prepared to engage in more readily – is the challenge that we are facing now.

I’m less worried about professional development in the formal sense. I think that centers for teaching and learning have a big role to play. I think we would make much more progress with this if there were more opportunity in people’s regular, everyday lives as faculty to talk about teaching and learning and to have their contributions recognized. And I think that will happen. I do think there’s been change in the right direction, but there’s a long way to go in many departments before the conversation goes beyond just a one small group of enthusiasts or perhaps the faculty appointed to the curriculum committee. I think the work of those committees focused on undergraduate education need to be upheld as more central to the work of our institutions and not just shoved off to one side.

However, we need to remember, just like we do for our students, what it’s like for a faculty member to be a novice in this pedagogical conversation. But if we keep working on this and have more occasions for graduate students and faculty to talk about teaching and learning, and more department chairs who see this as important and include it in faculty meetings, that will help. Indeed, you could list a whole number of ways in which to make more about our teaching lives public and raise pedagogical literacy to a higher level.

DW: I did a presentation a few weeks ago about the need for elevating teaching in a research university. And the response I got from faculty was, “Yes, but … how do you do that? Because we’re a research university.” This is what we get a lot. “We’re a research university. We don’t have time to carve out for something else.” How do you respond to that?

MH: That is partly why we need leaders who keep reminding us that we’re there for an educational mission – for both undergraduates and graduate students, especially when you are talking about a research university. I think we need our faculty evaluation systems to make a larger space for teaching and educational leadership. But I don’t discount the difficulties given the way the larger political economy of higher education has developed and the competitive world in which institutions believe they live.

DW: And that was the theme at AAC&U, this conflict between prestige and learning, that if we are aiming everything toward prestige, that doesn’t fit with this culture of how do we learn from our mistakes, how do we help all students learn more. That’s a big challenge.

MH: It is a challenge. I was struck yesterday (at the Bay View Alliance Meeting) when Howard Gobstein (of the Association of Public and Land Grant Universities) said that we are going so slow and that society is changing so fast and we aren’t keeping up, that this is urgent. And I’m saying to myself fine, if it’s that urgent why has society pulled away from supporting our public institutions? I think that’s part of the problem. I don’t think we need to take this on ourselves entirely, the critique that we are just not doing enough.

DW: That’s partly what we talked about. We need to be more of an advocate.

MH: We need to be advocating. We need higher education leaders who can make a better case for public support for higher education. We need less talk about and less focus on austerity. I was reading a book recently on public universities – Christopher Newfield’s The Great Mistake. At one University of California institution, in the English major, Newfield said, there was only room for students to have “exactly one” small seminar class because they just don’t have enough faculty to offer more. If the need for our work as educators is as urgent as people think, then we need to more generously resource that effort. Obviously we can be smarter in how we work and improve and do better. And we are going to run into that prestige competition as a countervailing force. That’s how we live. But I don’t think it’s fair to just say that colleges and universities are failing. I think society is failing. If they need higher education to do something different, which I think they do, we cannot any longer settle for the kind of education that we have been providing to most of our students. Those good jobs in the workforce and the life they supported are no longer viable for a growing number of college graduates. We need to do better by the students. But we aren’t going to be able to do that without broader social support. Faculty will need time, security, resources, and encouragement to improve teaching and learning and educational programs so that our colleges and universities can serve today’s students well. That’s my view.

************

This article also appears on the website of the Bay View Alliance.

How small changes can improve our teaching

By Derek Graf

As instructors, we sometimes look for ways to create big changes in our courses, departments, and degree programs. Searching for complete overhauls to our teaching practices, we risk losing sight of the small changes we can make in our next class meeting.

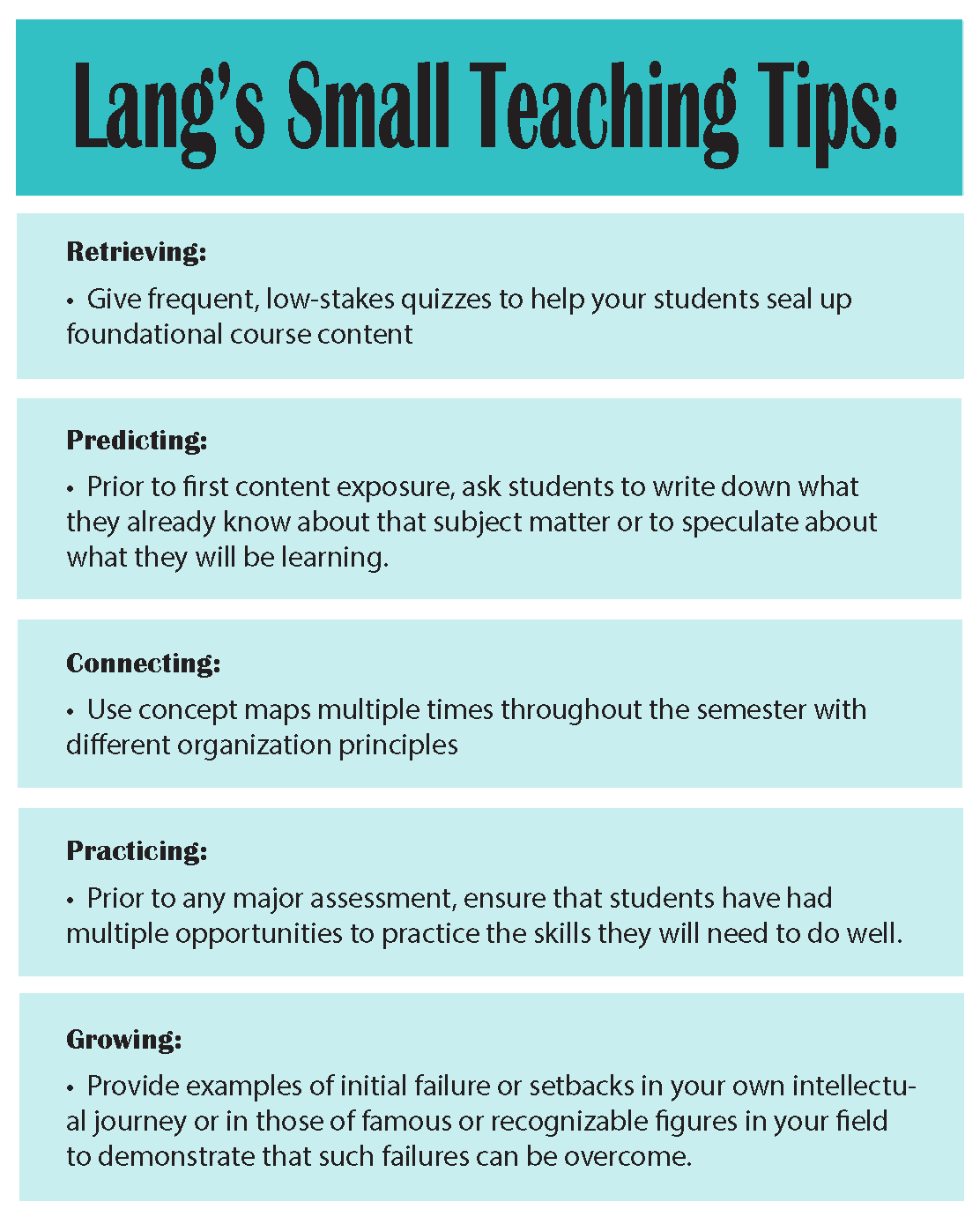

James M. Lang, author of Small Teaching: Everyday Lessons from the Science of Learning, believes that fundamental pedagogical improvement is possible through incremental change (4). For example, he explains how asking students to make predictions increases their ability to understand course material and retrieve prior knowledge. He offers various strategies for incorporating prediction exercises into the classroom, such as utilizing a brief pretest on new material at the beginning of class, asking students to predict the outcome of a problem, or closing class by asking students to make predictions about material that will be covered in the next class (60). As Lang says, “predictions make us curious,” and as instructors we can encourage student curiosity if we allow them to make predictions about the course material.

In Small Teaching, Lang shows how instructors can capitalize on minor shifts to a lesson plan to motivate students, help them connect with new content, and give them time to practice the skills required on formal essays and exams. As Lang explains in the introduction, small teaching defines a pedagogical approach “that seeks to spark positive change in higher education through small but powerful modifications to our course design and teaching practices” (5). Lang argues that big changes begin with each new class, and he provides numerous strategies for enacting those changes.

An English professor and director of the Center for Teaching Excellence at Assumption College in Worcester, Mass., Lang says that small teaching practices can be utilized by teachers from any discipline, in any course, at any point in the semester. Lang understands that many instructors, such as adjuncts and GTAs, lack the time and the resources necessary to make major curriculum shifts in their departments. Small teaching allows instructors of all levels to innovate their teaching and generate enthusiasm in the classroom in ways that are incremental, deliberate, and, most importantly of all, accessible.

Lang identifies accessibility as the key to the potential success of small teaching: “Teaching innovations that have the potential to spur broad changes must be as accessible to underpaid and overworked adjuncts as they are to tenured faculty at research universities” (5). The small teaching activities Lang offers fulfill this criteria because, “with a little creative thinking, they can translate into every conceivable type of teaching environment in higher education, from lectures in cavernous classrooms to discussions in small seminar rooms, from fully face-to-face to fully online courses and every blended shade in between” (6). Lang has either practiced or directly observed every piece of advice he offers in Small Teaching, and these activities fall into one of three categories:

- Brief (5-10 minute) classroom or online learning activities.

- One-time interventions in a course.

- Small modifications in course design or communication with your students.

Knowledge, understanding and inspiration

Over three sections, organized under the broad categories of “Knowledge,” “Understanding,” and “Inspiration,” Lang provides numerous ways to implement small teaching, even during the opening minutes of tomorrow’s class. For example, Lang shows how we can motivate students to develop an emotional response to the course material by telling great stories: “Once class has started, the simplest way to tap the emotions of your students is to use the method that every great orator, comedian, emcee, and preacher knows: begin with a story” (182). Drawing from the research of experimental psychologist Sarah Cavanagh, Lang explains how “when emotions are present, our cognitive capacities can heighten; so if we open class by capturing the attention of our students and activating their emotions with a story, we are priming them to learn whatever comes next” (182). While great stories don’t necessarily lead to great class sessions, they do allow for students to create an emotional bond with the course material.

The above example proved to be my favorite of the activities outlined in Small Teaching. As an instructor of freshman composition, I often feel as though my students enter college lacking a positive emotional relationship to writing. They associate writing with an instructor’s judgment on their intellectual capabilities.

Realizing this, I decided to open one of my classes with a personal story about a former instructor of mine who would humiliate students for their lack of quality prose. After sharing an anecdote in which I was the recipient of a particularly harsh and public critique, I admitted how his experience affected my confidence while also explaining that I did not let this moment define my identity as a writer or a student. I asked my students if they had any similar experiences with writing. Sure enough, several of them shared that their relationship with writing was dominated by the “red pen” approach of a past instructor, and some of them shared stories of procrastination gone wrong.

This conversation allowed me to explain my approach to grading and assessing student writing, increase my transparency as an instructor, and also commiserate with students about the difficulties of writing for an academic audience. My decision to begin class with a personal story altered the emotional climate of the room, and my students’ engagement with the course material benefited from that shift.

“Tell Great Stories” is just one of many activities Lang shares throughout Small Teaching. Balancing a personal tone with clear explanations of the psychological and cognitive research backing his argument, Lang ultimately collapses the binary between “small teaching” and “big changes.” Perhaps they are one and the same, each informing the other, and leading toward necessary shifts in higher education, one class at a time.

Addressing universities’ built-in barriers to success

By Doug Ward

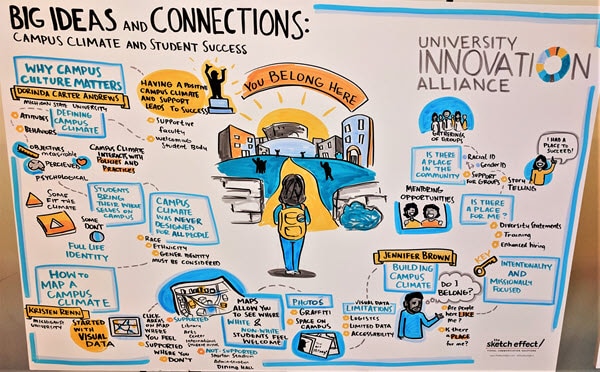

The overarching message from a meeting of the University Innovation Alliance was as disturbing as it was clear: Research universities were built around faculty and administrators, not students, and they must tear down systemic barriers quickly and completely if they hope to help students succeed in the future.

About 75 representatives from the alliance’s member institutions gathered at Michigan State University last week to share ideas and to talk about successes, challenges and impediments to student success. The alliance comprises 11 U.S. research universities working to improve graduation rates among a wider range of students. Since its start five years ago, it has led efforts in predictive analytics, proactive advising, completion grants, and college-to-career activities. It has also created a fellows program that allows for concentrated attention on barriers to student success.

Speakers at the meeting certainly celebrated those efforts,but over and over they referred to systemic problems that can no longer be ignored.Those problems underlie less-than-stellar retention and graduation rates,especially among first-generation and underrepresented students, and amongthose who come from less-than-wealthy families. They loom large when youconsider that the future of universities depends on their ability to serve thevery students they once pushed away.

“There’s this belief system that low-income, first-generation, students of color, when they drop out, that there’s something about them. It’s not an indictment of the entire system,” said Bridget Burns, executive director of the UIA. That is, there’s an “unintended value system” that tells students that when they fail, it’s individual weakness, not a problem with the university.

Research universities were created to serve the elite, not the masses, and were meant to foster a “reproduction of privilege,” Burns said. Degrees were meant to be rare and difficult to earn. As a result, universities are filled with booby traps that stop students from moving toward a degree.

Burns didn’t elaborate on that, but it’s easy to see the ways that universities were designed around the needs of faculty members and administrators, not students. Students must jump through hoop after bureaucratic hoop to register for classes, arrange for financial aid, pay their bills, meet requirements, and even meet with an advisor. They attend classes at times most convenient for instructors and gather in classrooms that focus on the instructor. Universities also do a poor job of helping students learn how to learn in a college environment.

Two roads, two perceptions

Frank Dooley, senior vice provost for teaching and learning at Purdue, used two disparate images to illustrate the murky path that students must traverse. One image was of a wide open highway with smooth pavement disappearing into the horizon. The other was of a spaghetti bowl of urban interchanges, twisting and turning into a seemingly impenetrable combination of highways. Those of us involved in higher education generally see the path through universities as the open road, he said. Students see the impenetrable tangle.

That’s just the administrative side. Another barrier is the disconnect between faculty members and student success. Most faculty members do indeed care about the undergraduates in their classes, and many have transformed their courses in ways that improve class climate, retention, student interaction, critical thinking, and learning. Those efforts count for little in a university rewards system that makes research productivity the primary means of evaluation, though. As several people at the UIA meeting noted, that rewards system encourages faculty to distance themselves from students, who essentially become an impediment to tenure and promotion. It also provides no incentive to become involved in broader university efforts to help students succeed.

Grit and the myth of individualism

Claire Creighton, director of the Academic Success Center at Oregon State, provided another example of universities’ many systemic barriers as she talked of how the idea of “grit” had spread into conversations across institutions. On its own, it’s a fine concept, she said: Students need to work through adversity. Persistence pays off.

In many ways, though, grit is an extension of the American myth of the self-made man – yes, the myth is generally male-centric – the idea that a person can achieve anything through hard work and persistence, that those of no means have the same opportunity to rise to the top as those with abundant wealth. It’s a myth embedded in popular culture through stories of individual success and rugged individualism. Legislators, policy makers and universities themselves have perpetuated that myth by turning a degree into an individual commodity and an individual financial burden rather than a shared accomplishment of a democratic society.

As Creighton said, grit has become equated with student success. Those who succeed have grit and those who fail don’t. By looking at it in those terms, we create a sense of deficiency among students by blaming them for their failure rather than looking into systemic problems.

“What is it about institutions that requires students to be gritty and resilient, to overcome adversity, in order to achieve?” she asked.

I agree, but students will face repeated adversity once they leave a university. We need to help them develop the grit they will need for long-term success by helping them work through failures – and by making failure a learning experience rather than a dead end – while supporting them as they build confidence and develop skills.

Genyne Royal, assistant dean for student success initiatives at Michigan State, explained one way of doing that by paying more attention to what she called the “murky middle,” students with GPAs of 2.0 to 2.6. We generally focus most on students on academic probation, she said, and we miss those borderline students who could easily slip toward failure.

The ‘murky middle’ and the ‘secret sauce’

She equated student success to a mysterious “secret sauce” that all universities hope to find. Some years we add brown sugar, she said. Other years we add hot sauce. That is, the process must change constantly as students and their unique needs change.

That process must also help us see our campuses through the eyes of students, as Jennifer Brown, vice provost and dean for undergraduate education at the University of California, Riverside, reminded those at the UIA meeting. We too often forget what students see when they look at our programs and visit our campuses. Most certainly they consider what they will learn and where a degree will lead them. Two of the most important factors have little to do with academics, though, Brown said, and everything to do with a sense of belonging:

Are there others here like me?

Is there a place here for me?

Preparing for ‘seismic shifts’

An article this week from EAB, the educational data and consulting organization, echoed the concerns I heard at the meeting of the University Innovation Alliance. It conveyed a sense of urgency for colleges and universities to prepare for “seismic shifts” in the coming decade as demographics change and the number of high school graduates declines. Melanie Ho, executive director of EAB, recently completed a series of one-on-one discussions with university presidents. She said that administrators spoke of the urgent need for “systemic, holistic change across campus.” Institutions must focus on what makes them unique, she said, while breaking down silos and quickly pushing through changes that might usually take years to accomplish.

That need for holistic change came up in many discussions and presentations at the University Innovation Alliance gathering, as did the importance of cooperation across institutions. John Engler, interim president of Michigan State and a former Michigan governor, said global competition for talent, weak graduation rates, and growing cynicism about higher education all pointed to the need for change.

“Universities think we can’t go away,” Engler said. “Well, the world is changing. Maybe that will change.”

Enrollment figures foreshadow challenges for universities

Enrollment reports released last week hint at the challenges that colleges and universities will face in the coming decade.

Across the Kansas regents universities, enrollment fell by the equivalent of 540 full-time students, or 0.72 percent. Emporia State, Fort Hays State, Wichita State and the KU Medical Center all showed slight increases, but full-time equivalent enrollment fell at Pittsburg State (3.98 percent), Kansas State (3.09 percent), and the KU Lawrence and Edwards campuses (0.49 percent). Enrollment at community colleges fell 2.6 percent.

Those numbers reflect the regents’ shift to a metric that focuses on credit hours rather than a count of the number of students. Total undergraduate credit hours are divided by 15 and graduate credit hours by 12 to get the full-time equivalency metric. More than 60 percent of students at regents institutions enroll only part time, the regents said in a news release, and the full-time equivalency counts adjust for that. At KU’s Lawrence and Edwards campuses, 16.2 percent of students are part time. That up about 2.5 points since 2013 but still considerably lower than it was in the 1990s.

KU reported(Link unavailable) that the total number of students across its campuses grew by 63, to 28,510, although the regents’ full-time equivalency total was 24,246. KU’s growth in head count came from the medical center. On the Lawrence and Edwards campuses, the number of students declined by 76. And though the freshman class grew, diversity declined in all categories.

Without doubt, KU had several strong components in its report. The most impressive was that nearly 84 percent of 2017’s freshman class returned to the university this year. That’s an increase of 4 to 6 points from just a few years ago and the highest KU has ever recorded. That growth reflects many factors, including higher admission standards and efforts to improve teaching, advising and student outreach.

Retaining students will grow increasingly important in the coming years as U.S. birthrates decline. An analysis by Nathan Grawe of Carleton University suggests that attendance at regional four-year colleges and universities will drop by more than 15 percent by 2029. Fewer births means fewer potential students, something that could prove particularly troubling for universities in the Midwest and Northeast, where declines are expected to be the steepest.

Universities like KU rely increasingly on undergraduate tuition dollars to pay the bills, especially as states reduce funding for higher education, so a large decline in in the number of students would have significant budget consequences. Many universities have ratcheted up out-of-state recruiting and increased financial aid in hopes of attracting more students. Some have been forced to reduce out-of-state tuition rates to attract more students.

This all grows increasingly important as KU considers a budget model that would allocate departmental resources in part on the number of undergraduate credit hours. More students would mean more money. Fewer students would mean fewer departmental resources, putting ever more pressure on small departments that provide important perspectives on an ever-changing world but that are never likely to attract large numbers of students.

Long-term predictions are notoriously inaccurate, so there’s no guarantee that any single university will face an extreme drop in the number of students. You don’t have to look far, though, to see what might happen. Enrollment at Kansas State dropped by nearly 1,000 students last year, and its enrollment declined each year between 2015 and 2017. That forced a budget cut of $15 million.

To make up for declining numbers of undergraduates, many universities have developed new master’s programs, many of them online, to tap into a demand for new skills and new credentials. Between 2000 and 2015, the number of master’s degrees granted at U.S. institutions rose by more than 60 percent. They have also added online classes for undergraduates to allow more flexibility for students who often work more than 20 hours a week to pay their bills.

The vast majority of tuition dollars still come from undergraduates, and without a doubt, attracting even the same number of students will grow increasingly challenging in the coming decade. Universities can’t just play numbers games, though. Volumes of students and credit hours may pay the bills, but unless universities elevate the importance of high-quality teaching and learning, those numbers mean little. In an increasingly competitive environment, the quality of teaching matters immensely.

Neil deGrasse Tyson on professors’ communication problem

Neil deGrasse Tyson, who has made a career out of explaining science to the public, offered some strong criticism of higher education in a recent interview with The Chronicle of Higher Education. He said that a misguided rewards systems discouraged professors from reaching out beyond a small group of like-minded colleagues.

“If communicating with the public were valued in the tenure process, they’d be better at it. This is an easy problem to solve. If 20 percent of the evaluation for tenure were based on how well you communicate with the public, that’s a game changer. All of a sudden universities open up, and people learn about what you’re doing there, whether it’s bird wings or paramecia.

“But in the end, universities don’t really care. Put that in big letters.”

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Why sustaining educational change requires collaboration

By Doug Ward

Howard Gobstein issued both a challenge and a warning to those of us in higher education.

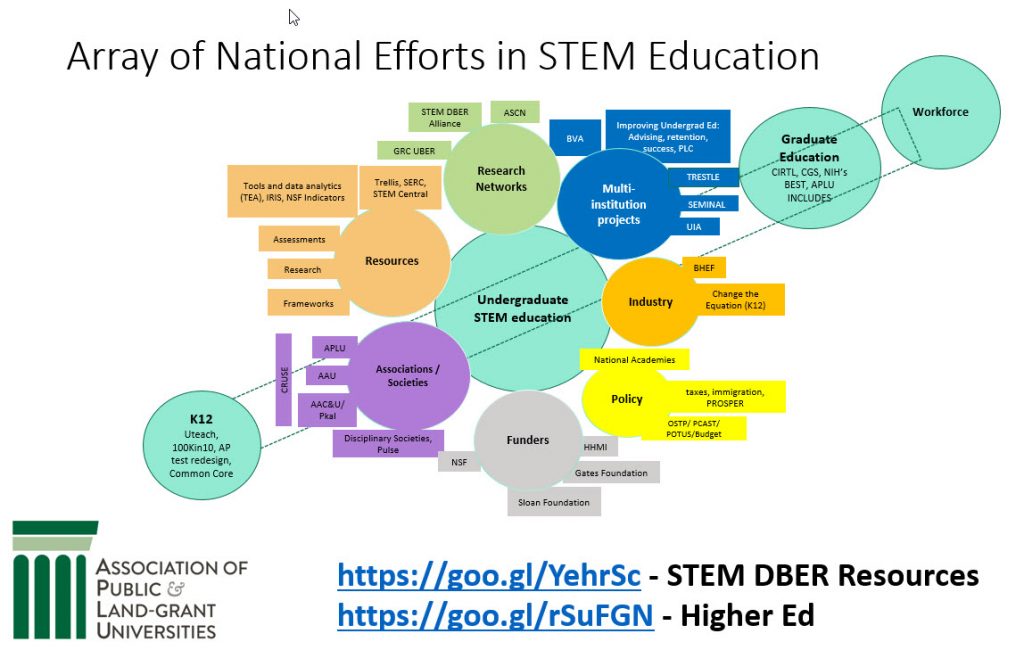

Universities aren’t keeping up with the pace of societal change, he said, and the initiatives to improve education at the local, state and national levels too often work in isolation.

“We’d better start talking to one another,” said Gobstein, vice president for research policy and STEM education at the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities.

Gobstein spoke in Lawrence last week at the annual meeting of TRESTLE, a network of faculty and academic leaders who are working with colleagues in their departments to improve teaching in science, technology, engineering and math. Pressures are building both inside and outside the university to improve education, he said, citing changing demographics, rising costs, advances in technology, and demands for accountability among the many pressure points. Universities have created initiatives to improve retention at the institutional level. Departments and disciplines, especially in STEM, have created their own initiatives. Most work independently, though.

“There are almost two different conversations occurring, I would argue,” Gobstein said. “There are those that are pushing overall and those that are pushing within STEM.”

Not only that, but national organizations have created STEM education initiatives focusing on K-12, undergraduate education, graduate education, and industry and community needs. Those initiatives often overlap, but all of them are vital for effecting change, Gobstein said.

“To transform and to make it stick, there has to be something going on across all of these levels,” he said.

Universities must also work more quickly, especially as outside organizations draw on technology to provide alternative models of education.

“There are organizations out there, there are institutions out there that are going to change the nature of education,” Gobstein said. “They are already starting to do that. They are nipping away at universities. And we ignore them at our peril.”

Gobstein made a similar argument last year at a meeting of the Bay View Alliance, a consortium of North American research universities that are working to improve teaching and learning. Demographics are changing rapidly, he said, but STEM fields are not attracting enough students from underrepresented minority groups and lower economic backgrounds.

“That’s not entirely the responsibility of institutions, but they have a big role to play,” Gobstein said. “To the extent that we can transform our STEM education, our classes, our way of dealing with these students, the quicker we will be able to get a larger portion of these students into lucrative STEM fields.”

Change starts at individual institutions and in gateway courses that often hold students back, he said. Research universities must value teaching and learning more, though.

“It’s the recognition that teaching matters. It’s the recognition that counseling students matters,” Gobstein said.

Higher education is also under pressure from parents, students and governments to improve teaching and learning, to make sure students are prepared for the future, and to provide education at a price that doesn’t plunge families into debt.

“We seem to be losing ground with them as far as their confidence in our institutions to be able to provide what those students need for their future, particularly at a price that they are comfortable with,” Gobstein said.

At TRESTLE, Gobstein challenged participants with some difficult questions:

- What does teaching mean in an era of rapidly changing technology?

- How do we measure the pace of change? How do we know that we are doing better this year than in previous years?

- How do we make sure the next generation of faculty continues to bring about change but also sustains that change?

He also urged participants to seek out collaborators on their campuses who can provide support for their efforts but also connect them with national initiatives.

“What we’re really trying to do is to change how students learn, and we’re trying to make sure that all students have access and opportunity,” Gobstein said.

Despite the many challenges, Gobstein told instructors at TRESTLE that the work they were doing to improve teaching and learning was vital to the future of higher education.

“You are doing work that is some of the most important work any of us can think of doing,” Gobstein said.

“The nation needs you.”

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Putting KU’s leadership in learning on display

By Doug Ward

The University of Kansas has gained international attention with its work in student-centered learning over the past five years.

Grants from the National Science Foundation, the Teagle Foundation, and the Association of American Universities have helped transform dozens of classes and helped faculty better understand students and learning. Participation in the Bay View Alliance, a North American consortium of research universities, has helped the university bolster its efforts to improve teaching and learning. And participation in organizations like the International Society for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, the Association of American Colleges and Universities, and the AAU has provided opportunities for KU faculty to share the rich work they have done in improving their courses.

KU’s leadership in student-centered education will be on display at home this week as instructors and administrators from a dozen research universities and educational organizations gather in Lawrence for a three-day institute on teaching and learning. The institute, which begins Thursday, is part of the annual meeting of TRESTLE, a network of faculty and academic leaders who are working with colleagues in their departments to improve teaching in science, technology, engineering and mathematics classes at research universities. TRESTLE is an acronym for transforming education, stimulating teaching and learning excellence.

Attendees will participate in workshops on many facets of course transformation and active learning organized around a theme of sustaining change and broadening participation in student-centered education. Among the speakers are Howard Gobstein, executive vice president of the Association of Public and Land Grant Universities; Pat Hutchings, a senior scholar at the National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment; and Mary Huber, a senior scholar at the Bay View Alliance, an international organization working to build leadership for educational change.

“KU has been a hub for transforming teaching and learning for several years,” said Andrea Greenhoot, director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and leader of the TRESTLE network. “TRESTLE has allowed us to expand that community beyond campus and connect with faculty at other universities.”

That collaborative approach has been central to the TRESTLE network and to this week’s institute.

“Teaching is often seen as a solitary activity,” Greenhoot said. “It doesn’t have to be that way. Our philosophy at CTE has always been that great teaching requires community. The TRESTLE community provides role models, engages faculty in intellectual discussions about teaching, gives instructors opportunities to reflect on their work, and creates a platform for sharing ideas and results.”

TRESTLE was formed three years ago after Greenhoot, Caroline Bennett, associate professor of engineering, Mark Mort, associate professor of biology, and partners at six other universities received grants totaling $2.5 million from the National Science Foundation. Their work has focused on supporting the development of STEM education experts who work within academic departments. These experts collaborate with other instructors in their departments to incorporate teaching innovations that shift the emphasis away from lecture and engage students in collaborative activities, discussion, problem-solving and projects that lead to better learning. Over the last three years, faculty members involved with TRESTLE have transformed more than 100 courses.

The transformation efforts have been impressive, Greenhoot said, but maintaining the changes after the grant ends in two years will be crucial. Blair Schneider, the program director of TRESTLE, has been coordinating this week’s activities with that in mind.

“We will be asking participants to take on some challenging questions during their time in Lawrence,” Schneider said. “How can we sustain the momentum we’ve built up over the last three years? What will it take to keep departments focused on improving student learning? How do we keep all this going? Everyone involved with TRESTLE has been energized as they have shared ideas and rethought their classes. We want to make sure that energy continues.”

As part of the institute, several KU faculty members are opening their classrooms so that participants can see the results of course transformation. Those instructors are from geology, chemistry, biology, civil engineering, and electrical engineering and computer science. Participants will also have opportunities to see active learning classrooms that KU has created over the past few years.

Open textbook workshop

If you haven’t looked into using open resources in your classes, you should. Open access materials replace costly textbooks, saving students millions of dollars a year even as they provide flexibility for instructors.

Two workshops at KU Libraries in October will help instructors learn how to adopt, adapt and even create open resources for their classes. Josh Bolick, scholarly communication librarian in the Shulenburger Office of Scholarly Communication and Copyright, will the lead the workshops as part of Open Access Week, an international event aimed at increasing awareness of open access materials.

Bolick’s workshops, “Open Textbooks and How They Support Teaching and Learning,” will be held from 9:30 to 11 a.m. on Oct. 19 and Oct. 23 in Watson Library, room 455. You can register here.

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

A new approach to introductory physics seems to improve student learning

By Doug Ward

Data analytics holds great potential for helping us understand curricula.

By combining data from our courses (rubrics, grades, in-class surveys) with broader university data (student demographics, data from other courses), we can get a more meaningful picture of who our students are and how they perform as they move through our curricula.

Sarah LeGresley Rush and Chris Fischer in the KU physics department offered a glimpse into what we might learn with a broader pool of university data at a departmental colloquim on Monday. LeGresley Rush and Fischer explained analyses suggesting that a shift in the way an early physics class is structured had led to improvements in student performance in later engineering classes.

That reference to engineering is correct. Engineering students take introductory physics before many of their engineering classes, and the physics department created a separate class specifically for engineering majors.

A few years ago, Fischer began rethinking the structure of introductory physics because students often struggled with vector mathematics early in the course. In Spring 2015, he introduced what he called an “energy first” approach in Physics 211, focusing on the principle of energy conservation and the use of more applied calculus. The other introductory class, Physics 210, maintained its traditional “force first” curriculum, which explores classical mechanics through the laws of motion and uses little applied calculus. Both classes continued their extensive use of trigonometry and vectors, but Physics 211 adopted considerable material on differentiation and integration, which Physics 210 did not have.

LeGresley Rush, a teaching specialist in physics, joined Fischer, an associate professor, in evaluating the changes in two ways. First, they used results from the Force Concept Inventory, an exam that has been used for three decades to measure students’ understanding of concepts in introductory physics. They also used university analytics to see how students in the two introductory sections fared in a later physics course and in three engineering courses.

In both analyses, students who completed the revised physics courses outperformed students who took the course in the original format. The biggest improvements were among students with ACT math scores below 22. In every grouping of ACT scores they used (22-24, 25-27, 28-30, and above 30), students who took the revised course outperformed those who took the course in the traditional format. Those on the lower end gained the most, though.

They next looked at how students in the two sections of introductory physics did in the next course in the department sequence, General Physics II. The results were similar, but LeGresley Rush and Fischer were able to compare student grades. In this case, students who completed the transformed course earned grades nearly a point higher in General Physics II than those who took the traditional course.

Finally, LeGresley Rush and Fischer used university data to track student performance in three engineering courses that list introductory physics as a requirement: Mechanical Engineering 211 (Statics and Introduction to Mechanics) and 312 (Basic Engineering Thermodynamics), and Civil Engineering 301 (Statics and Dynamics). Again, students who took the revised course did better in engineering courses, this time by about half a grade point.

“Why?” Fischer said in an earlier interview. “We argue that it’s probably because we changed this curriculum around and by doing so we incorporated more applied mathematics.”

He pointed specifically to moving vector mathematics to later in the semester. Vector math tends to be one of the most difficult subjects for students in the class. By helping students deepen their understanding of easier physics principles first, Fischer said, they are able to draw on those principles later when they work on vectors. There were also some changes in instruction that could have made a difference, he said, but all three physics classes in the study had shifted to an active learning format.

Fischer went to great lengths during the colloquium to point out potential flaws in the data and in the conclusions, especially as skeptical colleagues peppered him with questions. As with any such study, there is the possibility for error.

Nonetheless, Fischer and LeGresley Rush made a compelling case that a revised approach to introductory physics improved student learning in later courses. Perhaps as important, they demonstrated the value of university data in exploring teaching and curricula. Their project will help others at KU tackle similar questions.

The physics project is part of a CTE-led program to use university data to improve teaching, student learning, and retention in science, technology, engineering and math courses. The CTE program, which involves seven departments, is funded by a grant from the Association of American Universities. The Office of Institutional Research and Planning has provided data analysis for the teams.

A helpful tool for finding articles blocked by paywalls

A Chrome browser plug-in called Unpaywall may save a bit of time by pointing you to open access versions of online journal articles ensconced behind paywalls.

The plug-in, which is free, works like this:

When you find a journal article on a subscription-only site, Unpaywall automatically searches for an open version of the article. Often these are versions that authors have posted or that universities have made available through sites like KU Scholar Works. If Unpaywall finds an open copy of the article, it displays a green circle with an open lock on the right side of the screen. You click on the circle and are redirected to the open article.

It’s pretty slick. Unpaywall says its database has 20 million open access articles. It was integrated into Web of Science last year and is now part of many library systems.

Scott Hanrath, associate dean of libraries, said KU Libraries integrated a version of UnPaywall into its system in late 2016. If the “Get at KU” database doesn’t find a match for a source that libraries has access to, it tries the UnPaywall database as an alternative and provides a link if an open version of the article is available.

The Get at KU function is especially helpful in online searches, and the additional database opened even more options for finding articles quickly. I added UnPaywall to my search toolkit, as well. It seems like a useful addition, especially when I’m off campus.

You can read more about Unpaywall in a recent issue of Nature.

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Motivation, mental health and advice for a new academic year

By Doug Ward

The beginning of an academic year is a time of renewal. Our courses and our students start fresh, and we have an opportunity to try new approaches and new course material.

The beginning of an academic year is also a time for sharing advice, information, experiences, and insights. Here are some interesting tidbits I think are worth sharing.

Motivating students (part 1)

Aligning course goals with student goals is an important element of motivating students, David Gooblar, a lecturer in rhetoric at the University of Iowa, writes in The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Many students say they are motivated by grades – actually, many seem obsessed with grades – but that type of motivation doesn’t benefit them intellectually in the long term.

To help stimulate intrinsic motivation, Gooblar uses a low-stakes writing assignment in which students explain their goals for the course and how they hope the course will benefit them in the long term. Gooblar draws on those goals to adapt his class during the semester. Flexibility is important, he says, because it helps show students that he is willing to respond to their needs. That can be a powerful motivator.

I have also had success with having students write about their goals. I frame that in terms of learning goals, explaining to students that I have goals for the class but that I want them to pursue individual goals, too.

Most students struggle with writing individual learning goals because they have never had to think about learning as something they have control over. That thought makes them uncomfortable. They generally see school as a place where someone tells them what to do. I have found that waiting until the second or third week of class makes the process go more smoothly. By then, students have a good sense of what the class is about and they generally offer more thoughtful goals than they might in the first week.

Returning to those goals later in the class is important. I have students reflect on their learning goals at midterm, revising them if they wish, and again at the end of the class. That helps students assess what they have gained intellectually and what they still need to work on. It gives them a sense of accomplishment and helps them gain confidence in self-guided learning. It also gives me additional assessment information, as I ask students to explain which elements of the class helped them learn the most and which didn’t work as well.

Motivating students (part 2)

Shannon Portillo, associate professor of public affairs and administration, offers additional advice for motivating students.

Writing in Inside Higher Ed, Portillo, who is also the assistant vice chancellor for undergraduate programs at the Edwards Campus, has students help set guidelines for class engagement, using the exercise to help them feel invested in the class from the start.

At the end of the class, she asks students to evaluate their participation. They give her a suggested grade on their participation and provide evidence to back it up. She doesn’t always agree with their assessment, and ultimately determines the grade herself. Men tend to give themselves high marks, she says, while women tend to be more critical of themselves. The evaluation process helps students reflect on their contributions to the class and on their own learning.

Motivation (part 3). Faculty Focus offers additional tips on motivating students, including offering good feedback; helping students understand how learning works; providing engaging course materials and activities and explaining their relevance; and making greater use of cooperative and collaborative work.

Technology can help, but …

In a survey by Campus Technology, 73 percent of faculty members said that technology had made their jobs easier and 87 percent said it had improved their ability to teach. On the other hand, 19 percent said technology had made their job harder or much harder.

The survey did not say how technology had made things more difficult, but a comment on the article blamed it on a lack of training that ties pedagogy to the use of technology. That makes sense, but sometimes instructors fail to take advantage of the many available resources. KU has many resources for learning technology, including desk-side coaching and frequent workshops.

Student writing: No help needed?

In a recent survey by the Primary Research Group, only 8 percent of freshmen and sophomores said they thought they needed help with grammar and spelling. Yes, 8 percent.

Just as troubling, 46 percent of all students said they needed no additional writing instruction in their college classes.

Apparently, those 46 percent haven’t read any of the papers they have turned in or the email messages they have sent.

My intent isn’t to bash college students. Rather, it’s to remind instructor that as we help students, we sometimes need to remind them that they need our help and that resources like the KU Writing Center can provide crucial assistance.

The survey was reported by Inside Higher Ed.

Mental health and students

A growing percentage of students say they suffer from depression, anxiety and other mental health issues. That holds true for both undergraduates and graduate students.

At KU, for instance, Counseling and Psychological Services reported year-over-year increases in visits of 1 percent (November) to 73 percent (May) in the 2017-18 academic year.

One of the most important things faculty members can do is to pay attention to students and help them find the resources they need. Make sure that students know about Counseling and Psychological Services. I’ve made several calls to CAPS over the years, helping students schedule appointments with counselors. CAPS has other resources like drop-in hours with peer educators and group therapy sessions.

The Office of Student Affairs is another important resource. Its website provides an extensive list of advice and services for students and faculty members.

The Conversation noted recently that two of the biggest challenges to helping students with psychological issues are reluctance to talk about mental health and a reluctance to reach out for help. Instructors can help break down that stigma by being empathetic and accessible. They shouldn’t try to be psychological counselors. That’s not their role. They can listen to students, though, offer empathy and support, and help them take that first step toward getting help.

A final thought

A quote from Ryan Craig, managing director of University Ventures and author of A New U: Faster + Cheaper Alternatives to College, helps put issues of student mental health, attitude and motivation into context. In an interview with EdSurge, he said:

“We have developed this cult that you’re either going to go to college or if you don’t, maybe you’ll end up on Skid Row. I’m being a little facetious—but not that facetious. It literally has evolved to that point. A bachelor’s degree is the ticket to success and not having a bachelor’s degree is opposite.”

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

New CTE program helps spur curriculum innovation

By Doug Ward

Putting innovative curricular ideas into practice takes time and coordination among instructors, especially when several classes are involved.

To help jump-start that process, CTE has created a Curriculum Innovation Program and selected four teams of faculty members who will transform important components of their curricula over the coming year.

Each of the four teams will receive $10,000 to $12,000 for the project, along with up to $5,000 for team members to visit an institution that has had success in innovating its curriculum. The awards, the largest that CTE has ever made, were made possible by a donation from Bob and Kathie Taylor, KU alumni from Wichita.

The four teams were chosen from among 18 submissions from across the university. The winners, from environmental studies, geology, journalism and mass communications, and linguistics, were recognized at KU’s annual Teaching Summit on Thursday.

“We really wanted to see ideas that would have a big impact on student learning in a short amount of time,” said Andrea Greenhoot, director of the Center for Teaching Excellence. “We also wanted the changes to be sustainable. The four programs selected made the strongest cases for that.”