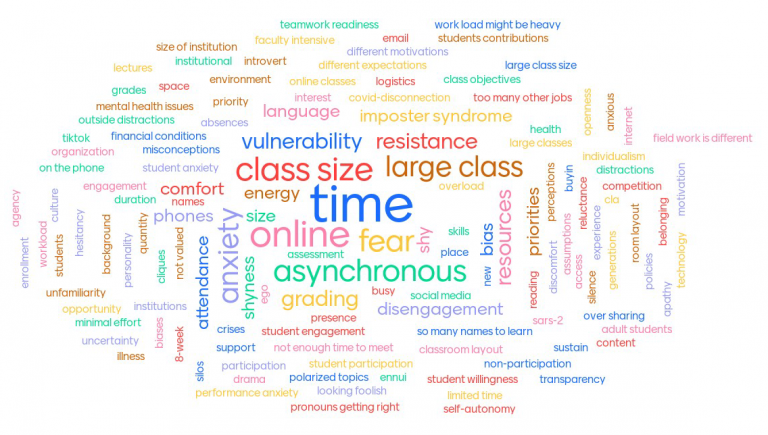

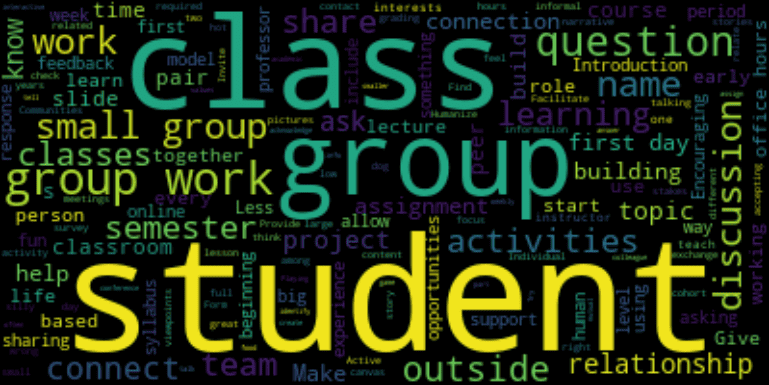

From summit poll, a list of ways to create community in classes

Peter Felten’s keynote message about building relationships through teaching found a receptive audience at this year’s Teaching Summit.

Felten, a professor of history and assistant provost for teaching and learning at Elon University, shared the stories of students who had made important connections with instructors and fellow students while at college. He used those stories to talk about the importance of humanity in teaching and about the vital role that community and connection make in students’ lives.

As part of his talk, Felten encouraged attendees to share examples of how they humanize their classes, asking:

What do you do to build relationships with and among students?

Summit attendees submitted about 140 responses. Felten shared some of them, along with a word cloud, but they were on screen only briefly. I thought it would be useful to revisit those responses and share them in a form that others could draw on.

To do that, I started with a spreadsheet from Felten that provided all the responses. I categorized most of them manually but also had ChatGPT create categories and a word cloud. Some responses had two or three examples, so I broke those into discrete parts. After editing and rearranging the categories and responses, I came up with the following list.

- Use collaborative work, projects, and activities

- Humanize yourself and students

- Learn students’ names

- Use ice breakers or get-to-know-you activities

- Create a comfortable environment and encourage open discussions

- Meet students individually

- Use active learning

- Provide feedback

- Engage students outside of class

Many of the responses could fit into more than one category, and some of the categories could certainly be combined. The nine I ended up with seemed like a reasonable way to bring a wide-ranging list of responses into a more comprehensible form, though.

Here’s that same list again, this time with example responses. It’s worth a look, not only to get new ideas for your classes but to reinforce your approaches to building community.

Use collaborative work, projects and activities

- Pulling up some students’ burning questions for small group discussions and then full class discussion leading to additional explanation and information in class.

- Think-pair-share in large lectures so students have several opportunities to connect with each other in different sized groups.

- Group work in consistent teams.

- We have a small cohort model that keeps students together in a group over two years and allows us to have close relationships with the students naturally.

- Timed “warm-up” conversations in pairs, usually narrative-based, often related to lesson/topic in some way; I always partner with someone, too.

- Form three-person groups early in the semester on easy assignments so the focus is on building relationships with each other.

- Group projects with milestones.

- Team-based learning.

- Using CATME to form student groups, which allows students to work in groups during class and facilitates group work and other interactions outside of class.

- Put students in small groups, give them a problem, ask them to solve it, and have them report back to the class.

- Group work in classrooms and online, in particular.

Humanize yourself and students

- Provide them your story to humanize your experience and how it may relate to theirs.

- Make myself seem more human, less intimidating. Share about myself outside of my role as professor makes students feel more comfortable to approach me and willingness to build that connection.

- I start class by sharing something about myself, especially something where I failed. The intention is to normalize failure and ambiguity. I also have a big Spider-Man poster in my office!

- Casually talking to the students about themselves, not only talking about the class or class-related topics.

- Being approachable by encouraging them to ask questions.

- Find topics of mutual connection – ex. International students and missing food from home.

- I tell my story as a first-generation student from rural America on day one. Try to be a human!

- Admit my own weaknesses and struggles!

- For groups that will be working together throughout the semester, I ask them to identify their values and describe how they will embody those in their work.

- Multidimensional identification of the instructor in the academic syllabus.

- Have students introduce themselves by sharing something very few people know about them. Each student in small classes, or triads in big classes.

- I remind them that the connections they make are the best part of the school.

- Sit down with them the first day of class to get to know them instead of standing in front of class.

- Acknowledge that they are humans with complex lives and being a student is only part of that life.

- In online classes, create weekly Zoom discussion groups that begin with a topic but quickly become personal stories and establish relationships and mutual support.

- Just ask how they feel and be honest.

- Make time and space in every class to collaborate and share something about themselves to help build relationships.

- I often start my classes off telling humorous but somewhat embarrassing moments of mistakes I’ve made in my career and life.

Learn students’ names

- Know their names before the class.

- Learning all students’ names and faces using pics on roll before the first day and making a game with students to see if I can get them right by end of class.

- Use photo rosters to make flashcards and know students’ names in a lecture hall when they show up on first day.

Use ice breaker or get-to-know-you activities

- At the beginning of the semester, I group students and have them come up with a team name. Amazingly, this seems to connect them and build camaraderie.

- I do a survey on the first day of class to ask students about themselves, what they want to do when they graduate, etc. Then I have a starting point to start chatting before class starts.

- Detailed slide on who I am and my path to where I am today, including getting every single question wrong on my first physics exam.

- Each student creates an introduction slide with pictures and information about themselves. Then I create a class slide deck and post on Canvas.

- Introductions in-person AND in Canvas so students can network outside of class with required peer responses.

- Relationship over content: Take the first day of class to focus on building relationships. Then every class period have an activity that focuses on relationship building.

- Circulate, contact, names, stories.

- Asking a brief get-to-know-you question each week

- Online classes: Introductions include “tell me something unique or interesting about you” and my response includes how I connect with / relate to / admire that uniqueness.

- I teach prospective educators. The second week of class I have them “teach” a lesson about themselves. They create a PowerPoint slide, share info, and answer questions from their peers.

- On the syllabus, include fun pictures of things you do outside the classroom and share some hobbies to help connect with students.

- Students introducing other students.

- Ask if a hot dog is a sandwich.

- Find shared experiences with an exercise—e.g., “What places have you been before coming here?”

- Have an email exchange with every student, sharing what our ideal day off is as part of an introductory syllabus quiz.

Meet students individually

- Student meetings at beginning of semester.

- Office hours, sitting among the students.

- Individual student hours meetings twice a semester (it’s a small class).

- Offer students extra credits if they come to my office hours during the first two weeks of class.

- Encouraging open office hours with multiple students to connect across classes and disciplines.

- One-on-ones with students.

- Mandatory early conference w professors.

- Required instructor conference, group work, embedded academic support.

- Coffee hours: informal time for students to meet with me and their peers.

- Allow time for group work when the instructor can talk with the small groups of students.

Use active learning

- Less lecture and more discussion-based activities.

- Less lecturing; being explicit about the values and principles that connect student interests.

- Active learning in classrooms to build connections between students and help them master content.

- Ask more questions than give answers.

- Help students connect the dots between the classroom, social life, professional interests, and their family.

Create a comfortable environment and encourage open discussions

- Questions of opinion – not right or wrong.

- Pulling up some students’ burning questions for small group discussions and then full class discussion, leading to additional explanation and information in class.

- Not just be accepting of different viewpoints, but guide discussions in a way that students are also accepting of each other’s.

- Give students opportunity to debate a low-stakes topic: Are hot dogs sandwiches?

- Model that asking “dumb” questions is OK and where learning happens.

- Group students for low-stakes in-class activities. Give them prompts to help get to know each other.

- Encouraging them to communicate with each other in discussion.

- Accept challenges (acknowledge student viewpoints rather than instant dismissal).

- Role Playing.

- Let them talk about their own interests.

- Conduct course survey often throughout the semester.

- Mindfulness activities.

- Students are more likely to ask friends for help. So in class I highlight their knowledge and encourage them to share.

- Food!

- Each class period starts with discussion about a fun/silly topic and a group dynamics topic.

- Good idea from colleague: assign someone the role of asking questions in small groups.

Provide feedback

- Providing feedback is showing care and support for students.

- Share work, peer feedback.

- Peer evaluations to practice course skills.

- Personal responses with assignments and group learning efforts.

- Provide individualized narrative feedback on assignments.

Engage students outside of class

- Invite students for outside-class informal cultural activities and events.

- Facilitate opportunities for students to connect outside of class time.

- In-person program orientations from a department level.

As the academic year begins, think community and connection

In a focus group before the pandemic, I heard some heart-wrenching stories from students.

One was from a young, Black woman who felt isolated and lonely. She mostly blamed herself, but the problems went far beyond her. At one point, she said:

“There’s some small classes that I’m in and like, some of my teachers don’t know my name. I mean, they don’t know my name. And I just, I kind of feel uncomfortable, because it’s like, if there’s some kids gone but I’m in there, I just want them to know I’m here. I don’t know. It’s just the principle that counts me.”

I thought about that young woman as I listed to Peter Felten, the keynote speaker at last week’s Teaching Summit. Felten, a professor of history at Elon University, drew on dozens of interviews he had conducted with students, and connected those to years of research on student success. Again and again, he emphasized the importance of connecting with students and helping students connect with each other. That can be challenging, he said, especially when class sizes are growing. The examples he provided made clear how critical that is, though.

“There’s literally decades and decades of research that says the most important factor in almost any positive student outcome you can think about – learning, retention, graduation rate, well-being, actually things like do they vote after they graduate – the single biggest predictor is the quality of relationships they perceive they have with faculty and peers,” Felten said.

Moving beyond barriers

Felten emphasized that interactions between students and instructors are often brief. It would be impossible for instructors to act as long-term mentors for all their students, but students often need just need reassurance or validation: hearing a greeting from the instructor, having the instructor remember their name, getting meaningful feedback. Quality matters more than quantity, Felten said. The crucial elements are making human connections and helping students feel that they belong.

Creating that interaction isn’t always easy, Felten said. He gave an example of a first-generation student named Oliguria, whose parents had emphasized the importance of independence.

“She said she had so internalized this message from her parents that you have to do college alone, that when she got to college she thought it was cheating to ask questions in class,” Felten said. “That was her word: cheating. It’s cheating to go to the writing center, cheating to go to the tutoring center.”

Instructors need to help students move past those types of beliefs and to see the importance of asking for help, Felten said.

Another challenge is helping students push past impostor syndrome, or doubts about abilities and feelings that someone will say they don’t belong. That is especially prevalent in academia, Felten said. Others around you can seem so poised and so knowledgeable. That can make students feel that they don’t belong in a class, a discipline, or even in college because they have learned to feel that “if you’re struggling, there must be something wrong with you.”

That misconception can make it difficult for students to recover from early stumbles and to appreciate difficulty as an important part of learning.

“I don’t know about your experience,” Felten said. “What I do is hard. But we don’t tell students that, right? They think if it’s hard, there’s something wrong with them.”

Because of that, students hesitate to ask for help and don’t want their instructors to know about their struggles. As one student told Felten, “pride gets in the way of acknowledging that I don’t understand something.”

Small interactions with huge consequences

Getting past that pride can make a huge difference, Felten said. He gave the example of Joshua, a 30-year-old community college student who nearly dropped out because he found calculus especially difficult.

“I suddenly began to have these feelings like, I didn’t belong in this class, that my education, what I was trying to achieve wasn’t possible,” Joshua told Felten. “And my goals were just obscenely further away than I thought they were.”

He spoke to his professor, who told him to go home and read about impostor syndrome. That helped Joshua feel more confident. He sought out a tutor and eventually got an A in the class.

The professor, Felten said, was an adjunct who taught only one semester. Joshua met with him only once, but that meeting had far-reaching effects. Joshua completed his associate’s degree and later graduated from Purdue.

Felten called Joshua’s professor “a mentor of the moment.” That means “paying attention to the person right in front of you and being able to give them the right kind of challenge, the right kind of support, the right kind of guidance that they need right then.”

Felten also talked about another student, José, who wanted to become a nurse. José loved life sciences but bristled at a requirement to take a course outside his major. He signed up for a geology class simply because it fit into his schedule, and he vowed to do as little as possible. Ultimately, Felten said, the class ended up being “one of the most powerful classes he had taken.”

José told Felten: “My professor made something as boring as rocks interesting. The passion she had, her subject, was something that she loved.”

José never got to know the professor personally, but the way she conducted the class – interactively and passionately – was transformative, Felten said.

“The most important thing is that this class became a community,” José told Felten. “She made us interact with each other and with the subject. It just came together because of her passion.”

The importance of good feedback

Felten also talked about Nellie, a student who started college just as the pandemic hit. In a writing course, she liked the instructor’s feedback on assignments so much that she later took another class from the same professor, even though she never talked directly to her.

“She would have this little paragraph in the comments saying, you did this super well in your paper. And that little bit of encouragement, even though I’m not face to face with this teacher at all, made a world of difference to me,” Nellie told Felten. “We’ve never met in person or even had a conversation, but she has made a huge positive difference in my education.”

Instructors can easily overlook the impact of something like feedback on written assignments, but Felten said they can be validating. He cited a study from a large Australian university that found that the biggest predictor of undergraduate well-being was the quality of teaching. The authors of the study said students weren’t expecting their instructors to be counselors or therapists or even long-term mentors.

“They’re asking us to do our job well, which is to teach well, to assess clearly and to teach as if learning is an interactive human thing, to connect with each other and with the material,” Felten said.

The importance of community

I’ll go back to the young woman I interviewed a few years ago, and how isolated she felt in her classes and how alone she felt outside classes.

“I think it’s just really interesting,” she said. “I see a lot of different faces every day, but I still feel so isolated. And I know sometimes that’s like my problem. But I do feel like I should know way more people. And I just, I want to know more people.”

Her story was heart-wrenching. She and another student – a white transfer student – talked about getting “vibes” from classmates that pushed them deeper into isolation and made life at the university challenging. Neither had gained a sense of belonging at the university, even though both desperately sought a sense of connection.

In his talk at the Teaching Summit, Felten said the antidote to that was to create community in our classes.

“The most important place for relationships in college is the classroom,” Felten said. “If they don’t happen there, we can’t guarantee they happen for all students.”

He also added later: “If we know that’s true, why don’t we organize our courses, why don’t we organize our curriculum, why don’t we organize our programs, our universities as if that was a central factor in all of the good things that can happen here?”

Why indeed.

Doug Ward is associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications at the University of Kansas.

Research points to AI’s growing influence

If you are sitting on the fence, wondering whether to jump into the land of generative AI, take a look at some recent news – and then jump.

- Three recently released studies say that workers who used generative AI were substantially more productive than those who didn’t. In two of the studies, the quality of work also improved.

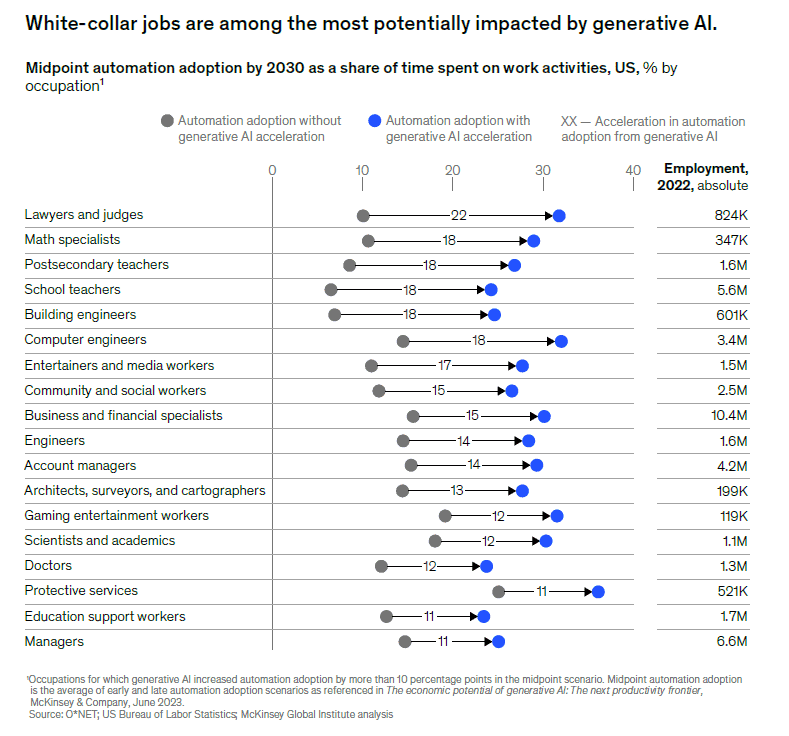

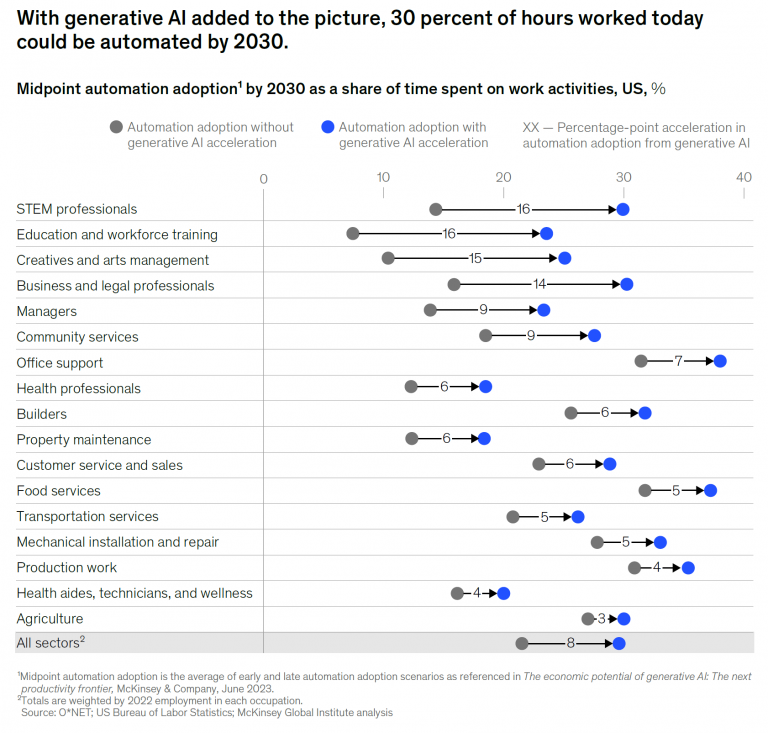

- The consulting company McKinsey said that a third of companies that responded to a recent global survey said they were regularly using generative AI in their operations. Among white-collar professions that McKinsey said would be most affected by generative AI in the coming decade are lawyers and judges, math specialists, teachers, engineers, entertainers and media workers, and business and financial specialists.

- The textbook publisher Pearson plans to include a chatbot tutor with its Pearson+ platform this fall. A related tool already summarizes videos. The company Chegg is also creating an AI chatbot, according to Yahoo News.

- New AI-driven education platforms are emerging weekly, all promising to make learning easier. These include: ClaudeScholar (focus on the science that matters), SocratiQ (Take control of your learning), Monic.ai (Your ultimate Learning Copilot), Synthetical (Science, Simplified), Upword (Get your research done 10x faster), Aceflow (The fastest way for students to learn anything), Smartie (Strategic Module Assistant), and Kajabi (Create your course in minutes).

My point in highlighting those is to show how quickly generative AI is spreading. As the educational consultant EAB wrote recently, universities can’t wait until they have a committee-approved strategy. They must act now – even though they don’t have all the answers. The same applies to teaching and learning.

A closer look at the research

Because widespread use of generative AI is so new, research about it is just starting to trickle out. The web consultant Jakob Nielsen said the three AI-related productivity studies I mention above were some of the first that have been done. None of the studies specifically involved colleges and universities, but the productivity gains were highest in the types of activities common to colleges and universities: handling business documents (59% increase in productivity) and coding projects (126% increase).

One study, published in Science, found that generative AI reduced the time professionals spent on writing by 40% but also helped workers improve the quality of their writing. The authors suggested that “ChatGPT could entirely replace certain kinds of writers, such as grant writers or marketers, by letting companies directly automate the creation of grant applications and press releases with minimal human oversight.”

In one of two recent McKinsey studies, though, researchers said most companies were in no rush to allow automated use of generative AI. Instead, they are integrating its use into existing work processes. Companies are using chatbots for things like creating drafts of documents, generating hypotheses, and helping experts complete tasks more quickly. McKinsey emphasized that in nearly all cases, an expert oversaw use of generative AI, checking the accuracy of the output.

Nonetheless, by 2030, automation is expected to take over tasks that account for nearly a third of current hours worked, McKinsey said in a separate survey. Jobs most affected will be in office support, customer service, and food service. Workers in those jobs are predominantly women, people of color, and people with less education. However, generative AI is also forcing changes in fields that require a college degree: STEM fields, creative fields, and business and legal professions. People in those fields aren’t likely to lose jobs, McKinsey said, but will instead use AI to supplement what they already do.

“All of this means that automation is about to affect a wider set of work activities involving expertise, interaction with people, and creativity,” McKinsey said in the report.

What does this mean for teaching?

I look at employer reports like this as downstream reminders of what we in education need to help students learn. We still need to emphasize core skills like writing, critical thinking, communication, analytical reasoning, and synthesis, but how we help students gain those skills constantly evolves. In terms of generative AI, that will mean rethinking assignments and working with students on effective ways to use AI tools for learning rather than trying to keep those tools out of classes.

If you aren’t swayed by the direction of businesses, consider what recent graduates say. In a survey released by Cengage, more than half of recent graduates said that the growth of AI had left them feeling unprepared for the job market, and 65% said they wanted to be able to work alongside someone else to learn to use generative AI and other digital platforms. In the same survey, 79% of employers said employees would benefit from learning to use generative AI. (Strangely, 39% of recent graduates said they would rather work with AI or robots than with real people; 24% of employers said the same thing. I have much to say about that, but now isn’t the time.)

Here’s how I interpret all of this: Businesses and industry are quickly integrating generative AI into their work processes. Researchers are finding that generative AI can save time and improve work quality. That will further accelerate business’s integration of AI tools and students’ need to know how to use those tools in nearly any career. Education technology companies are responding by creating a large number of new tools. Many won’t survive, but some will be integrated into existing tools or sold directly to students. If colleges and universities don’t develop their own generative AI tools for teaching and learning, they will have little choice but to adopt vendor tools, which are often specialized and sold through expensive enterprise licenses or through fees paid directly by students.

Clearly, we need to integrate generative AI into our teaching and learning. It’s difficult to know how to do that, though. The CTE website provides some guidance. In general, though, instructors should:

- Learn how to use generative AI.

- Help students learn to use AI for learning.

- Talk with students about appropriate use of AI in classes.

- Experiment with ways to integrate generative AI into assignments.

Those are broad suggestions. You will find more specifics on the website, but none of us has a perfect formula for how to do this. We need to experiment, share our experiences, and learn from one another along the way. We also need to push for development of university-wide AI tools that are safe and adaptable for learning.

The fence is collapsing. Those who are still sitting have two choices: jump or fall.

AI detection update

OpenAI, the organization behind ChatGPT, has discontinued its artificial intelligence detection tool. In a terse note on its website, OpenAI said that the tool had a “low rate of accuracy” and that the company was “researching more effective provenance techniques for text.”

Meanwhile, Turnitin, the company that makes plagiarism and AI detectors, updated its figures on AI detection. Turnitin said it had evaluated 65 million student papers since April, with 3.3% flagged as having 80% to 100% of content AI-created. That’s down from 3.5% in May. Papers flagged as having 20% or more of content flagged rose slightly, to 10.3%.

I appreciate Turnitin’s willingness to share those results, even though I don’t know what to make of them. As I’ve written previously, AI detectors falsely accuse thousands of students, especially international students, and their results should not be seen as proof of academic misconduct. Turnitin, to its credit, has said as much.

AI detection is difficult, and detectors can be easily fooled. Instead of putting up barriers, we should help students learn to use generative AI ethically.

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications.

Why generative AI is now a must for graduate classes

Instructors have raised widespread concern about the impact of generative artificial intelligence on undergraduate education.

As we focus on undergraduate classes, though, we must not lose sight of the profound effect that generative AI is likely to have on graduate education. The question there, though, isn’t how or whether to integrate AI into coursework. Rather, it’s how quickly we can integrate AI into methods courses and help students learn to use AI in finding literature; identifying significant areas of potential research; merging, cleaning, analyzing, visualizing, and interpreting data; making connections among ideas; and teasing out significant findings. That will be especially critical in STEM fields and in any discipline that uses quantitative methods.

The need to integrate generative AI into graduate studies has been growing since the release of ChatGPT last fall. Since then, companies, organizations, and individuals have released a flurry of new tools that draw on ChatGPT or other large language models. (See a brief curated list below.) If there was any lingering doubt that generative AI would play an outsized role in graduate education, though, it evaporated with the release of a ChatGPT plugin called Code Interpreter. Code Interpreter is still in beta testing and requires a paid version of ChatGPT to use. Early users say it saves weeks or months of analyzing complex data, though.

OpenAI is admirably reserved in describing Code Interpreter, saying it is best used in solving quantitative and qualitative mathematical problems, doing data analysis and visualization, and converting file formats. Others didn’t hold back in their assessments, though.

Ethan Mollick, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, says Code Interpreter turns ChatGPT into “an impressive data scientist.” It enables new abilities to write and execute Python code, upload large files, do complex math, and create charts and graphs. It also reduces the number of errors and fabrications from ChatGPT. He says Code Interpreter “is relentless, usually correcting its own errors when it spots them.” It also “ ‘reasons’ about data in ways that seem very human.”

Andy Stapleton, creator of a YouTube channel that offers advice to graduate students, says Code Interpreter does “all the heavy lifting” of data analysis and asks questions about data like a collaborator. He calls it “an absolute game changer for research Ph.D.s.”

Code Interpreter is just the latest example of how rapid changes in generative AI could force profound changes in the way we approach just about every aspect of higher education. Graduate education is high on that list. It won’t be long before graduate students who lack skills in using generative AI will simply not be able to keep up with those who do.

Other helpful research tools

The number of AI-related tools has been growing at a mind-boggling rate, with one curator listing more than 6,000 tools on everything from astrology to cocktail recipes to content repurposing to (you’ve been waiting for this) a bot for Only Fans messaging. That list is very likely to keep growing as entrepreneurs rush to monetize generative AI. Some tools have already been scrapped or absorbed into competing sites, though, and we can expect more consolidation as stronger (or better publicized) tools separate themselves from the pack.

The easiest way to get started with generative AI is to try one of the most popular tools: ChatGPT, Bing Chat, Bard, or Claude. Many other tools are more focused, though, and are worth exploring. Some of the tools below were made specifically for researchers or graduate students. Others are more broadly focused but have similar capabilities. Most of these have a free option or at least a free trial.

- Research assistants like Research Rabbit, ARIA (an add-on to Zotero), Litmaps, Connected Papers, and ClioVis help scholars find and organize literature, visualize connections among ideas, share collections of research, and keep up with new research.

- Search tools like Consensus, Elicit, Scite, SciSpace, Snowball, System Pro, You, Metaphor, and Inciteful help guide researchers toward specific types of literature.

- Tools for interacting with articles. These allow researchers to query literature with natural language questions and to find ideas or connections they might have overlooked. They include Explainpaper, which allows you to highlight text and ask for explanations; PaperBrain; Sharly, which has a generous free version; ChatPDF; MapDeduce; Census GPT, which connects to U.S. Census data; Humata; Upword; OpenRead; PDF.ai; Kadoa; and Cerelyze, which allows you interact with articles and translate method into code.

- Summary tools provide quick synopses of articles, papers, and books, making it easier to work through large amounts of literature. These include Scholarcy, which highlights key areas of academic articles and allows you to build a personal library; Lateral; MapDeduce; ShortForm.ai, which uses a browser plugin; TinyWow, which offers a suite of free AI-powered tools; Summarize.tech and Eightify, which summarize YouTube videos; and BooksAI, which provides summaries of books.

- Several data tools allow researchers to query their quantitative data with natural language questions. These include Julius; Formulas HQ; Chatwithdata; Chatcsv; ChatNode; Tomat; Chartify; DataSquirrel; Chaindesk; and JADBio, which focuses on genomics, medicine, health, and drug discovery. Web-scraping tools like Simplescraper help automate time-consuming data-gathering.

- Writing tools like Jenni, Paperpal, Writefull, and Wisio promise to make academic writing easier.

How to use Code Interpreter

You will need a paid ChatGPT account. Jon Martindale of Digital Trends explains how to get started. An OpenAI forum offers suggestions on using the new tool. Members of the ChatGPT community forum also offer many ideas on how to use ChatGPT, as do members of the OpenAI Discord forum. (If you’ve never used Discord, here’s a guide for getting started.)

We can’t detect our way out of the AI challenge

By Doug Ward

Not surprisingly, tools for detecting material written by artificial intelligence have created as much confusion as clarity.

Students at several universities say they have been falsely accused of cheating, with accusations delaying graduation for some. Faculty members, chairs, and administrators have said they aren’t sure how to interpret or use the results of AI detectors.

I’ve written previously about using these results as information, not an indictment. Turnitin, the company that created the AI detector KU uses on Canvas, has been especially careful to avoid making claims of perfection in its detection tool. Last month, the company’s chief product officer, Annie Chechitelli, added to that caution.

Chechitelli said Turnitin’s AI detector was producing different results in daily use than it had in lab testing. For instance, work that Turnitin flags as 20% AI-written or less is more likely to have false positives. Introductory and concluding sentences are more likely to be flagged incorrectly, Chechitelli said, as is writing that mixes human and AI-created material.

As a result of its findings, Turnitin said it would now require that a document have at least 300 words (up from 150) before the document can be evaluated. It has added an asterisk when 20% or less of a document’s content is flagged, alerting instructors to potential inaccuracies. It is also adjusting the way it interprets sentences at the beginning and end of a document.

Chechitelli also released statistics about results from the Turnitin AI detector, saying that 9.6% of documents had 20% or more of the text flagged as AI-written, and 3.5% had 80% to 100% flagged. That is based on an analysis of 38.5 million documents.

What does this mean?

Chechitelli estimated that the Turnitin AI detector had incorrectly flagged 1% of overall documents and 4% of sentences. Even with that smaller percentage, that means 38,500 students have been falsely accused of submitting AI-written work.

I don’t know how many writing assignments students at KU submit each semester. Even if each student submitted only one, though, more than 200 could be falsely accused of turning in AI-written work every semester.

That’s unfair and unsustainable. It leads to distrust between students and instructors, and between students and the academic system. That sort of distrust often generates or perpetuates a desire to cheat, further eroding academic integrity.

We most certainly want students to complete the work we assign them, and we want them to do so with integrity. We can’t rely on AI detectors – or plagiarism detectors, for that matter – as a shortcut, though. If we want students to complete their work honestly, we must create meaningful assignments – assignments that students see value in and that we, as instructors, see value in. We must talk more about academic integrity and create a sense of belonging in our classes so that students see themselves as part of a community.

I won’t pretend that is easy, especially as more instructors are being asked to teach larger classes and as many students are struggling with mental health issues and finding class engagement difficult. By criminalizing the use of AI, though, we set ourselves up as enforcers rather than instructors. None of us want that.

To move beyond enforcement, we need to accept generative artificial intelligence as a tool that students will use. I’ve been seeing the term co-create used more frequently when referring to the use of large language models for writing, and that seems like an appropriate way to approach AI. AI will soon be built in to Word, Google Docs, and other writing software, and companies are releasing new AI-infused tools every day. To help students use those tools effectively and ethically, we must guide them in learning how large language models work, how to create effective prompts, how to critically evaluate the writing of AI systems, how to explain how AI is used in their work, and how to reflect on the process of using AI.

At times, instructors may want students to avoid AI use. That’s understandable. All writers have room to improve, and we want students to grapple with the complexities of writing to improve their thinking and their ability to inform, persuade, and entertain with language. None of that happens if they rely solely on machines to do the work for them. Some students may not want to use AI in their writing, and we should respect that.

We have to find a balance in our classes, though. Banning AI outright serves no one and leads to over-reliance on flawed detection systems. As Sarah Elaine Eaton of the University of Calgary said in a recent forum led by the Chronicle of Higher Education: “Nobody wins in an academic-integrity arms race.”

What now?

We at CTE will continue working on a wide range of materials to help faculty with AI. (If you haven’t, check out a guide on our website: Adapting your course to artificial intelligence.) We are also working with partners in the Bay View Alliance to exchange ideas and materials, and to develop additional ways to help faculty in the fall. We will have discussions about AI at the Teaching Summit in August and follow those up with a hands-on AI session on the afternoon of the Summit. We will also have a working group on AI in the fall.

Realistically, we anticipate that most instructors will move into AI slowly, and we plan to create tutorials to help them learn and adapt. We are all in uncharted territory, and we will need to continue to experiment and share experiences and ideas. Students need to learn to use AI tools as they prepare for jobs and as they engage in democracy. AI is already being used to create and spread disinformation. So even as we grapple with the boundaries of ethical use of AI, we must prepare students to see through the malevolent use of new AI tools.

That will require time and effort, adding complexity to teaching and additional burdens on instructors. No matter your feelings about AI, though, you have to assume that students will move more quickly than you.

Resources for energy-challenged faculty

The pandemic has taken a heavy mental and emotional toll on faculty members and graduate teaching assistants.

That has been clear in three lunch sessions at CTE over the past few weeks. We called the sessions non-workshops because the only agenda was to share, listen, and offer support. I offered some takeaways from the first session in March. In the most recent sessions, we heard many similar stories:

- Teaching has grown more complicated, the size of our classes has grown, and our workloads and job pressures have increased. Stress is constant. We are exhausted and burned out. “I feel hollow,” one participant said.

- Students need more than we can give. Many students are overwhelmed and not coming to class; they can’t even keep track of when work is due. They also aren’t willing to complete readings or put in minimal effort to succeed. All of that has drained the joy from teaching. “I have to psych myself up just to go to class some days,” one instructor said.

- We don’t feel respected, and we have never been rewarded for the vast amounts of intellectual and emotional work we have put in during the pandemic. Instead, the workload keeps increasing. “It feels like the message is: ‘We hear you. Now shut up,’ ” one participant said.

- We need time to heal but feel unable to ease up. Nearly all of those who attended the non-workshops were women, who often have additional pressures at home and feel that they will be judged harshly on campus if they try to scale back. “Society expects us to bounce right back, and we can’t,” one participant said.

Much has been written about the strain of the pandemic and its effect on faculty members and students. We can’t offer grand solutions to such a complex problem, which has systemic, cultural, psychological, and individual elements. We can offer support in small ways, though. So here is a motley collection of material intended to provide a modicum of inner healing. Some of these will require just a few minutes. Others will require a few hours. If none of them speak to you, that’s OK. Make sure to seek out the things that do brighten your soul, though.

An image (times 6)

I asked an artificial intelligence image generator called Catbird to create representations of serenity in everyday life. You will find three of those at the top of the page and three at the bottom. They won’t solve problems, but they do provide a momentary escape.

A song

“What’s Up,” by 4 Non Blondes. I recently rediscovered this early ’90s song, and its message seems more relevant than ever. It addresses the challenges of everyday life even as it provides a boost of inspiration. Even if you aren’t a fan of alt-rock, it’s worth a listen just to hear Linda Perry’s amazing voice.

A resource for KU employees

GuidanceResources. Jeff Stolz, director of employee mental health and well-being, passed along a free resource for KU employees. It is provided by the state Employee Assistance Program and can be accessed through the GuidanceResources site or mobile app. Employees can sign up for personal or family counseling, legal support, financial guidance, and work-life resources. The first time you log in, you will need to create an account and use the code SOKEAP.

A TED Talk

Compassion Fatigue: What is it and do you have it?, by Juliette Watt. Compassion fatigue, Watt says, is “the cost of caring for others, the cost of losing yourself in who you’re being for everyone else.”

A recent article

My Unexpected Cure for Burnout, by Catherine M. Roach. Chronicle of Higher Education (20 April 2023). Try giving away books and asking students to write notes in return.

A book

Unraveling Faculty Burnout: Pathways to Reckoning and Renewal, by Rebecca Pope-Ruark (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022). Pope-Ruark’s book focuses on women in academia and draws on many interviews to provide insights into burnout. The electronic version is available through KU Libraries.

A quote

From Pope-Ruark’s book.

I learned to offer myself grace and self-compassion, but it took a while, just as it had taken a while for my burnout to reach the level of breakdown. Once I was able to shift my mind-set away from needing external validation to understanding myself and my authentic needs, I was able to understand Katie Linder when she said, “It’s important for me to have that openness to growth, asking, ‘What am I supposed to be learning through the situation?’ even if it’s really hard or it’s not ideal or even great.”

If you don’t feel like devoting time to a book right now, consider Pope-Ruark’s article Beating Pandemic Burnout in Inside Higher Ed (27 April 2020).

A final thought

Take care of yourself. And find serenity wherever you can.

How should we use AI detectors with student writing?

When Turnitin activated its artificial intelligence detector this month, it provided a substantial amount of nuanced guidance.

The company did a laudable job of explaining the strengths and the weaknesses of its new tool, saying that it would rather be cautious and have its tool miss some questionable material than to falsely accuse someone of unethical behavior. It will make mistakes, though, and “that means you’ll have to take our predictions, as you should with the output of any AI-powered feature from any company, with a big grain of salt,” David Adamson, an AI scientist at Turnitin, said in a video. “You, the instructor, have to make the final interpretation.”

Turnitin walks a fine line between reliability and reality. On the one hand, it says its tool was “verified in a controlled lab environment” and renders scores with 98% confidence. On the other hand, it appears to have a margin of error of plus or minus 15 percentage points. So a score of 50 could actually be anywhere from 35 to 65.

The tool was also trained on older versions of the language model used in ChatGPT, Bing Chat, and many other AI writers. The company warns users that the tool requires “long-form prose text” and doesn’t work with lists, bullet points, or text of less than a few hundred words. It can also be fooled by a mix of original and AI-produced prose.

There are other potential problems.

A recent study in Computation and Language argues that AI detectors are far more likely to flag the work of non-native English speakers than the work of native speakers. The authors cautioned “against the use of GPT detectors in evaluative or educational settings, particularly when assessing the work of non-native English speakers.”

The Turnitin tool wasn’t tested as part of that study, and the company says it has found no bias against English-language learners in its tool. Seven other AI detectors were included in the study, though, and, clearly, we need to proceed with caution.

So how should instructors use the AI detection tool?

As much as instructors would like to use the detection number as a shortcut, they should not. The tool provides information, not an indictment. The same goes for Turnitin’s plagiarism tool.

So instead of making quick judgments based on the scores from Turnitin’s AI detection tool on Canvas, take a few more steps to gather information. This approach is admittedly more time-consuming than just relying on a score. It is fairer, though.

- Make comparisons. Does the flagged work have a difference in style, tone, spelling, flow, complexity, development of argument, use of sources and citations than students’ previous work? We often detect potential plagiarism that way. AI-created work often raises suspicion for the same reason.

- Try another tool. Submit the work to another AI detector and see whether you get similar results. That won’t provide absolute proof, especially if the detectors are trained on the same language model. It will provide additional information, though.

- Talk with the student. Students don’t see the scores from the AI detection tool, so meet with the student about the work you are questioning and show them the Turnitin data. Explain that the detector suggests the student used AI software to create the written work and point out the flagged elements in the writing. Make sure the student understands why that is a problem. If the work is substantially different from the student’s previous work, point out the key differences.

- Offer a second chance. The use of AI and AI detectors is so new that instructors should consider giving students a chance to redo the work. If you suspect the original was created with AI, you might offer the resubmission for a reduced grade. If it seems clear that the student did submit AI-generated text and did no original work, give the assignment a zero or a substantial reduction in grade.

- If all else fails … If you are convinced a student has misused artificial intelligence and has refused to change their behavior, you can file an academic misconduct report. Remember, though, that the Turnitin report has many flaws. You are far better to err on the side of caution than to devote lots of time and emotional energy on an academic misconduct claim that may not hold up.

No, this doesn’t mean giving up

I am by no means condoning student use of AI tools to avoid the intellectual work of our classes. Rather, the lines of use and misuse of AI are blurry. They may always be. That means we will need to rethink assignments and other assessments, and we must continue to adapt as the AI tools grow more sophisticated. We may need to rethink class, department, and school policy. We will need to determine appropriate use of AI in various disciplines. We also need to find ways to integrate artificial intelligence into our courses so that students learn to use it ethically.

If you haven’t already:

- Talk with students. Explain why portraying AI-generated work as their own is wrong. Make it clear to students what they gain from doing the work you assign. This is a conversation best had at the beginning of the semester, but it’s worth reinforcing at any point in the class.

- Revisit your syllabus. If you didn’t include language in your syllabus about the use of AI-generated text, code or images, add it for next semester. If you included a statement but still had problems, consider whether you need to make it clearer for the next class.

Keep in mind that we are at the beginning of a technological shift that may change many aspects of academia and society. We need to continue discussions about the ethical use of AI. Just as important, we need to work at building trust with our students. (More about that in the future.) When they feel part of a community, feel that their professors have their best interests in mind, and feel that the work they are doing has meaning, they are less likely to cheat. That’s why we recommend use of authentic assignments and strategies for creating community in classes.

Detection software will never keep up with the ability of AI tools to avoid detection. It’s like the game of whack-a-mole in the picture above. Relying on detectors does little more than treat the symptoms of a much bigger problem, and over-relying on them turns instructors into enforcers.

The problem is multifaceted, and it involves students’ lack of trust in the educational system, lack of belonging in their classes and at the university, and lack of belief in the intellectual process of education. Until we address those issues, enforcement will continue to detract from teaching and learning. We can’t let that happen.

Finding hope in community during another long semester

We called it a non-workshop.

The goal of the session earlier this month was to offer lunch to faculty members and let them talk about the challenges they continue to face three years into the pandemic.

We also invited Sarah Kirk, director of the KU Psychological Clinic, and Heather Frost, assistant director of Counseling and Psychological Services, to offer perspectives on students.

In an hour of conversation, our non-workshop ended up being a sort of academic stone soup: hearty and fulfilling, if unexpected.

Here’s a summary of some of the discussion and the ideas that emerged. I’ve attributed some material, although the wide-ranging conversation made it impossible to cite everyone who contributed.

Mental health

Typically, use of campus mental health clinics jumps in the two weeks before and the two weeks after spring break (or fall break). There is also a surge at the end of the semester. So if it seems like you and your students are flagging, you probably are.

- More people stepping forward. The pandemic drew more attention to and helped destigmatize mental health, encouraging more people to seek help, Frost said. One result is that clinics everywhere are full and not taking new clients. CAPS accepts initial walk-ins, but then students often have to schedule two weeks in advance.

- Small steps are important when students are anxious. Just doing something can seem daunting when anxiety is high, Kirk said, but taking action is important in overcoming anxiety.

- Connection is crucial. Connecting with peers and instructors helps give students a sense of belonging. Grad students seem especially glad to have opportunities to interact in person.

- Making class positive helps students. A feeling of belonging lowers anxiety and makes it more likely that students will attend class.

- International students and faculty have additional stress. Turmoil in home countries can add to stress, and many international students and faculty feel that they have no one to talk to about those troubles. Fellow students and instructors are often afraid to raise the subject, unintentionally amplifying anxieties. Those from Iran, Ukraine, and Russia are having an especially difficult time right now.

- Care for yourself. Frost encouraged faculty to listen to themselves and to seek out things they find meaningful. What is something that replenishes your energy? she asked. Students notice when instructors are anxious or fatigued, and that can add to their own stress. So set boundaries and engage in self-care.

Students seem to be working more

The perception among the group was that students were working more hours to earn money. That has added to missed classes, requests for deadline extensions or rescheduling of exams, and a need for incompletes.

- KU data. In a message after the meeting, Millinda Fowles, program manager for career and experiential learning, provided some perspective. She said that in the most recent survey of recent graduates, respondents said they worked an average of 22 hours a week while at KU. That’s up from 20 hours a week in previous surveys, with some students saying they worked more than 35 hours a week. In the 2021 National Survey of Student Engagement, KU students were asked whether the jobs they held while enrolled were related to their career plans. Responses were not at all: 32.8%, very little: 13.3%, some: 23%, quite a bit: 14.1% and very much: 16.8%.

Role of inflation. The need to work more isn’t surprising. Inflation has averaged 6% to 7% over the past two years, and food prices have jumped 9.5% just in the past year, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. According to the rental manager Zillow, the median rent of apartments it lists in Lawrence has increased 18% over the past year, to $1,300. Another site, RentCafe, lists average rent at $1,068, with some neighborhoods averaging more than $1,250 and others below $1,000.

- Hot job market. Bonnie Johnson in public affairs and administration said the job market in that field was so hot that students were taking full-time jobs in the second year of their master’s program. That is wearing them down.

- Effect on performance. Frost said students’ grades tend to go down if they work more than 20 to 25 hours a week.

Flexibility in classes

Many instructors are struggling with how much flexibility to offer students. They want to help students as much as possible but say that the added flexibility has put more strain on them as faculty members. Kirk agreed, saying that too much flexibility can increase the strain on both students and instructors and that instructors need to find the right amount of flexibility for themselves and their classes.

Balance structure and flexibility. Flexibility can be helpful, but students need structure and consistency during the semester. One of the best things instructors can do is to have students complete coursework a little at a time. Too much flexibility signals to students that they can let their work slide. If that work piles up, students’ stress increases, decreasing the quality of their work and increasing the chances of failure.

- Build options into courses. For instance, give students a window for turning in work, with a preferred due date and a final time when work will be accepted. Another option is to allow students to choose among assignment options. For instance, complete six of eight assignments. This gives students an opportunity to skip an assignment if they are overwhelmed. Another option is dropping a low score for an assignment, quiz or exam.

- Be compassionate with bad news, but also make sure students know there are consequences for missing class, missing work, and turning in shoddy work.

- Maintain standards. Students need to understand that they are accountable for assigned work. Giving them a constant pass on assignments does them a disservice because they may then be unprepared for future classes and may miss out on skills that are crucial for successful careers.

Sharing the burden

Ali Brox of environmental studies summed up the mood of the group: It’s often a struggle just to get through everything that faculty members need to do each day. The challenges of students are adding to that burden.

The daily burden of teaching has been increasing for years. In addition to class preparation and grading, instructors must learn to use and maintain a Canvas site, handle larger class sizes, keep up with pedagogy, rethink course materials for a more diverse study body, design courses intended to help students learn rather than to simply pass along information, assess student learning, and keep records for evaluation. In short, instructors are trying to help 21st-century students in a university structure created for 19th-century students.

Johnson added a cogent observation: In the past, professors generally had wives to handle the chores at home and secretaries to handle the distracting daily tasks.

There was one thing those professors didn’t have, though: CTE wasn’t there to provide lunch.

Follow-up readings

At the risk of adding to your burden, we offer a few readings that might offer some ideas for pushing through the rest of the semester.

- Jenny Odell Can Stretch Time and So Can You, Wired (14 March 2023). An interview with the author of How to Do Nothing and Saving Time: Discovering a Life Beyond the Clock. The message: We need to get past the time-is-money guilt complex and take control of our time.

- Course Correction: Students expect ‘total flexibility’ in the pandemic-era classroom. But is that really what they need?, by Beckie Supiano. Chronicle of Higher Education (13 February 2023).

- How Instructors Are Rethinking Late Work, by Carolyn Kuimelis. Chronicle of Higher Education (1 December 2022).

- Your Teaching Doesn’t Need to Be Perfect, by Beckie Supiano. Chronicle of Higher Education (1 September 2022).

- Beating Pandemic Burnout, by Rebecca Pope-Ruark. Inside Higher Ed (28 April 2020).

- Radical Self-Care, by Kerry Ann Rockquemore. Inside Higher Ed (6 May 2015). She suggests asking yourself three questions: What does your body need? What does your mind need? What does your spirit need?

- How to Listen Less, by Kerry Ann Rockquemore. Inside Higher Ed (4 November 2015). Provides three crucial questions for any faculty member: What are my responsibilities as a teacher? What are my students’ responsibilities? Where does my responsibility end and their responsibility begin?

Shifting grading strategies to improve equity

Martha Oakley couldn’t ignore the data.

The statistics about student success in her discipline were damning, and the success rates elsewhere were just as troubling:

- Women do worse than men in STEM courses but do better than men in other university courses.

- Students of color, first-generation students, and low-income students have lower success rates than women.

- The richer students’ parents are, the higher the students’ GPAs are.

“We have no problem failing students but telling ourselves we are doing a good job,” said Oakley, a professor of chemistry and an associate vice provost at Indiana University, Bloomington. “If we are claiming to be excellent but just recreating historical disadvantages, we aren’t really doing anything.”

Oakley spoke to about 40 faculty and staff members last week at a CTE-sponsored session on using mastery-based grading to make STEM courses more equitable. The session was part of a CTE-led initiative financed by a $529,000 grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, with participants from KU working with faculty members from 13 other universities on reducing equity gaps in undergraduate science education.

The work at KU, IU, and other universities is part of a broader cultural shift toward helping students succeed rather than pushing them out if they don’t do well immediately. Most disciplines have been changing their views on student success, but there has been increasing pressure on STEM fields, which have far lower numbers of women and non-white students and professionals than many other fields.

Oakley said she started digging deeper into university data about five years ago after attending a conference sponsored by the Association of American Universities and getting involved in IU’s Center for Learning Analytics and Student Success. She also began working with a multi-university initiative known as Seismic, which focuses on improving inclusiveness in STEM education.

She and some colleagues started by asking questions about the success rates of women in STEM but then recognized that the problem was far wider.

“And so we looked at each other and said, ‘Yeah, forget the women. Let’s worry about this bigger problem,’ ” Oakley said. “And we didn’t forget the women. We just had confidence that the things that we would do to address the other groups would also help women.”

Using analytics to guide change

In last week’s talk, she used many findings from Seismic and the IU analytics center as she made a case for changing the approach to teaching in STEM fields. For instance, she said, 20% to 50% of students at large universities fail or withdraw from early chemistry courses, with underrepresented minority students at the high end of that range. Students who receive a B or lower in pre-general chemistry courses have less than a 50-50 chance of succeeding in general chemistry.

She also talked about a personal revelation the data brought about. In 2011, she said, she received a university teaching award, and “by every metric, I knew I was doing my job really well.”

The data she saw a few years later suggested otherwise, showing that 37% of underrepresented students and 24% of the other students in her classes dropped or failed in the year she received the award.

“The major part of the story is we’ve all been trained in our disciplines to teach in a certain way that really was never particularly effective,” Oakley said.

We have learned much about how people learn but have continued with ineffective teaching strategies. That needs to change, she said.

“One really simple thing we can do is to say we only give teaching awards to people who actually demonstrate that their students have learned something,” she said.

A mastery-based approach

To address the problem at IU, Oakley has been experimenting with a mastery-based approach to grading.

The way most of us grade exacerbates inequities, Oakley said. It emphasizes superficial elements (basically memorization) and does nothing to reward learning from mistakes, persistence, or teamwork – “all the things that matter in life.” Grades are also poor predictors of how well students will do in jobs or in graduate school, she said.

Mastery-based grading gives students multiple attempts to demonstrate understanding of course material. It is related to another approach, competency-based learning, which also gives students multiple opportunities but focuses on application rather than simple understanding.

Oakley started shifting her class to mastery-based grading by taking broad learning goals and breaking them into smaller components: things like identifying catalysts and intermediates, using reaction order, and explaining why rates change with temperature. She also eliminated a grading curve. That was especially hard, she said, because she had internalized the notion of grade distributions, an approach that punishes failure and provides little opportunity for students to learn from mistakes.

She still uses quizzes and exams, with students taking quizzes the evening before class and then working in groups the next day to create a quiz key. That helps them learn from mistakes, knowing they will see similar questions on a quiz the following week.

At KU, Chris Fischer and Sarah LeGresley Rush have used a similar approach in physics courses, with results suggesting that a mastery approach helps students learn concepts in ways that stay with them in later engineering courses.

Oakley’s initial work has also showed potential, with DFW rates in her class falling to 8% and the average grade rising to a B. That was better than other sections of the class, although students didn’t do as well in later courses. Oakley isn’t discouraged, though. Rather, she said, she continues to learn from the process, just as her students do.

“We’ve really only scraped the tip of the iceberg,” she said.

Building on experience

Oakley’s advocacy for equity in STEM education is informed by experience. When she started at IU in 1996, she said, she was the only woman in a department of 42. That was isolating and frustrating, she said. Through her work in STEM education, she hopes to improve the opportunities for women and students of color.

“We’ve got to be both equitable and striving for excellence,” she said.

Only through experimentation, failure, and persistence can we start breaking down systemic barriers that have persisted for too long, she said.

“The system is broken,” Oakley said. “We are not ready for the students of the future – or even the present.”

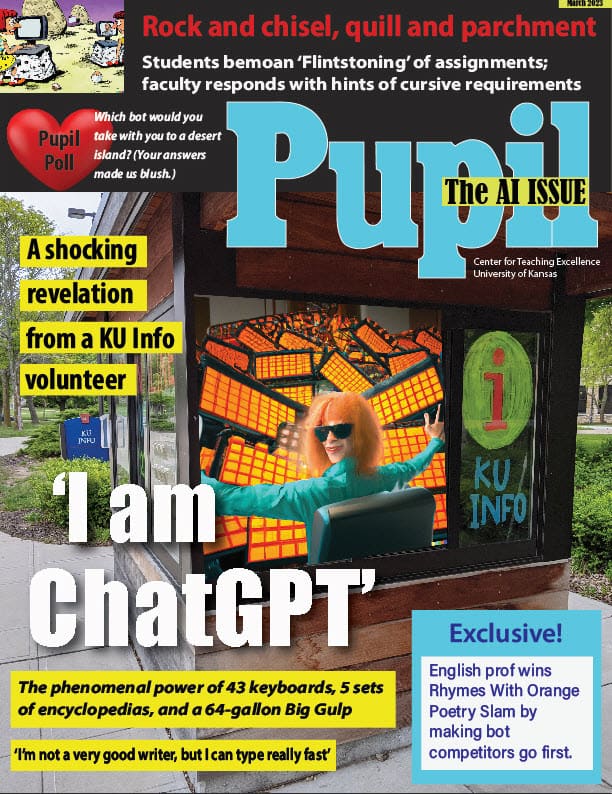

In this issue of Pupil, we mock the Age of AI Anxiety

We just looked at our office clock and realized that it was already March.

After we did some deep-breathing exercises and some puzzling over what happened to February, we realized the upside of losing track of time:

Spring break is only days – yes, days! – away.

We know how time can drag when you use an office clock as a calendar, though. So to help you get over those extra-long days before break, we offer the latest issue of Pupil magazine.

This is a themed issue, focusing on artificial intelligence, a topic that has generated almost as much academic froth as Prince Harry’s biography and Rhianna’s floating above the precious turf at the Super Bowl and singing “Rude Boy,” which we assumed was a critique of Prince Harry’s book.

OK, so we’re exaggerating about the academic froth, but we will say that we have uncovered a jaw-dropping secret about ChatGPT. It’s so astounding that we are sure it will make the days until break float by with ease.