How to lessen concerns about generative AI and academic integrity

Mahdis Mousavi, Unsplash

By Doug Ward

A new survey from the Association of American Colleges and Universities emphasizes the challenges instructors face in handling generative artificial intelligence in their classes.

Large percentages of faculty express concern about student overreliance on generative AI, diminishment of student skills, decreased attention spans, and an increase in cheating. The sample for the survey is not representative of all faculty, but it captures many of the concerns I have heard from instructors over the past three years.

There are no clear paths for adapting to the challenges of generative AI, and we have to take a multi-prong approach and experiment as we move forward.

That doesn’t mean we have to start from scratch, though. Taking some steps now, at the beginning of the semester, will make things easier as the semester progresses.

What you can do

In another post, I offered some suggestions to help make generative AI feel less overwhelming. Here are some steps you can take to make class go more smoothly and reduce problems related to academic integrity. Most of these are drawn from approaches that instructors are taking now.

- Work with students on a class policy. You should have a class policy in your syllabus, and CTE offers several approaches to creating a policy. You should explain that policy to students, but you can also encourage students to ask for clarifications or suggest additional language. That can help improve student acceptance of the policy — and improve it.

- Use alternative forms of grading. One of the biggest problems we face with assignments is that students’ quests for grades tend to block out everything else, including learning. CTE resources on alternative grading can help you consider ways to put learning above grades.

- Explain the why of assignments. All too often, we give students work to do without explaining how it will help them, how it connects with other disciplinary work, or how they will use it in the future. Helping students better understand the importance of assignments and the role they play in developing skills can improve motivation.

- Talk about research into generative AI and learning. Research into generative AI and education is still relatively sparse, but one thing is clear: Generative AI can’t learn for us. True learning requires effort, struggle, and occasional failure. Avoiding that work now will create problems later. (Another blog post provides a deeper look into the research on generative AI in teaching and learning.)

- Doing more in-class work. Class time is precious, and we should use it for the things that are most important. Some instructors have found that having students write, code or create in class reduces student desire to use generative AI, especially with low-stakes assignments. In-class work also allows instructors to work with groups or individual students, answering questions and providing guidance.

- Schedule individual meetings. Oral discussions can help instructors gauge student understanding. If students can’t explain their process for writing, coding or creating, they probably haven’t done enough (or any) work. Meetings don’t have to be long or complicated. Sara Wilson, a CTE faculty fellow from mechanical engineering, for instance, meets with students after every assignment, requiring additional work if students can’t explain the process they used in completing programming assignments. She often has more than 100 students, using class time for the individual meetings.

- Have students create a log. Reflection is an important part of learning. Having students create learning logs can promote reflection and allow instructors to see students’ thinking and the approaches they use as they complete work. Again, it is important to explain the purposes and benefits to students.

Much of the problem we have had with generative AI in education comes down to intrinsic motivation and trust. The education system emphasizes grades over learning, and students often see coursework as an obstacle. We need to tap into their intrinsic interests and chip away at the systemic barriers that inflate the importance of grades and turn teaching into policing.

Building trust is a crucial part of that process. That includes using approaches that encourage and reward effort, providing opportunities for questions and discussion, allowing students to learn from failures without grade-destroying penalties, and building a sense of community in each class. All of that requires work from instructors and students, but it also provides long-term benefits.

Doug Ward is associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications.

Don't let generative AI overwhelm you

By Doug Ward

I talk frequently about the need for faculty members to experiment with and adapt their teaching to generative artificial intelligence.

During a CTE session last week, an instructor mentioned how difficult that was, saying that “the landscape of AI is changing so rapidly that it seems impossible to keep up with.”

I agree. Not only that, but the rapid changes in generative AI seem to increase the pace of life. Daniel Burrus writes that “the world has shifted from a time of rapid change to a time of transformation.” That imposed change has pushed us to “react, manage crises, put out fires” rather than transform, which is something we do from within ourselves, he says.

My advice is to tune it out the flood of AI-related news. It’s important to understand the basic concepts of generative AI and to consider how you might take advantage of some of the tools. It is also crucial to talk with students frequently about use of generative AI, to help them understand how they might use generative AI on the job, and to help them develop AI literacy skills. You don’t have to keep up with every development, though.

Steps you can take

As the flood of news about generative AI roars past, try to ignore it. Instead, take a few steps that will empower both you and your students.

- Focus on a few tools. Find a generative AI tool you are comfortable with and stick with it. Learn how it works and what it can do. Start with Microsoft Copilot. It isn’t as powerful as some other tools, but it provides additional privacy and security when you log in with your KU credentials. It also allows you to create personalized chatbots called Copilot agents.

- It’s also worth learning to use NotebookLM, which allows you to create a folder of sources that Google’s Gemini draws on to answer questions. (Google says material in NotebookLM is not used in training generative AI models.) It is an excellent research tool, and it can serve as a learning tool for students if you upload course-related materials.

- Focus on your discipline. Rather than trying to keep up on the daily developments of generative AI, focus on the uses and the changes in your discipline. That will help cut through the noise.

- Learn with students. Instructors often feel uneasy about generative AI because it falls outside their area of expertise. Embrace that uneasiness and explain to students that everyone is trying to figure out where, how and whether this new technology fits into the work they do. Draw on the CTE generative AI course in Canvas. (Email dbward@ku.edu if you would like access.) Create exploratory assignments, have discussions about use of generative AI, and model a research mindset in helping students – and you – learn.

- Draw on CTE resources. Learn more about why students are drawn to generative AI and how you can adapt your classes to generative AI. Explore ways to integrate generative AI into your courses. Work with students on effective prompting. Try CTE-created tools for using Copilot agents, creating rubrics, and designing assignments. Join the Teams site on Generative AI in Teaching. It is a good place to ask questions and find information that we at CTE and others around campus share about developments in generative AI. (Contact dbward@ku.edu if you would like to be added to the site.)

Again, don’t try to stay abreast of everything related to generative AI. But do what you can to keep learning and adapting your courses.

Doug Ward is associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications.

Finding our way out of a digital loop

By Doug Ward

The phrase “humans in the loop" has become a cliché for the importance of overseeing the processes and output of generative artificial intelligence.

The rapid changes that generative AI have brought about, though, often make us feel like we are caught in an endless digital loop. Since the release of ChatGPT 3.5 three years ago, a bombardment of announcements and changes have made it hard to cut through the noise and gain clarity about the direction of this new AI-fueled world. ChatGPT and competing AI models have improved with head-spinning speed, new tools have been released almost daily, and those tools often blur the lines between the real and the artificial.

The music video above is my tongue-in-cheek commentary on the digital surrealism of the past three years.

I think back to what an instructor said during a workshop nearly three years ago: “I just wish someone would tell us what we are supposed to do.”

That wasn’t a plea for a mandate. It was an expression of exasperation of how education had been turned upside down, with no clear way to adapt.

I don’t see the changes slowing anytime soon. The only way to move through the maelstrom is to ground ourselves in core principles, embrace the pace of rapid change, and adapt our methods of teaching and learning. The good news is that the same AI tools that have challenged existing approaches to education can also empower us to rethink and remake learning for a generative world.

At CTE, that has been our message from the start. We may feel like humans in a loop, but our students need us to stop spinning and push through the maelstrom.

Use the break to experiment

Here’s a challenge as the semester winds down: Use winter break to introduce yourself (or re-introduce yourself) to generative artificial intelligence. Experiment with at least one generative artificial intelligence tool and find a way to integrate it into an assignment in the spring.

If you already feel comfortable with generative AI, experiment with a new tool and consider how you might use it to rethink instruction, create new approaches to online and in-person learning, enhance student skills, and deepen student understanding.

If you aren’t sure where to start, here are some ideas:

Copilot agents

Copilot agents allow you to give custom instructions and information to Copilot and create a personalized bot for your work or for your class. I’ve written previously about how to create Copilot agents. I’ve also created three agents to help with using Copilot. You’ll need to log in to Copilot with your KU credentials to use them.

- Copilot Agent Idea Guide. This tool will help you learn about Copilot agents, provide examples on how you might use them, and guide you through creation of your own agent.

- Agent Idea Generator. This is much like the Idea Guide, but it is intended to help students consider ways to use Copilot for learning. I created it for my class this semester, and students said they found it helpful.

- Rubric Assistant. This will help you create a rubric or help you improve an existing rubric.

NotebookLM

NotebookLM allows you to compile articles, links, videos, notes, and audio files, and use Google Gemini to explore those materials. Chat results in NotebookLM include links to passages in your material, allowing you to check the accuracy. NotebookLM also allows you to create concept maps, infographics, video and audio overviews, slide decks, flashcards, and quizzes from your materials.

Here’s a notebook I’ve called Uses of AI in Learning. It includes examples of assignments other instructors have used and ideas on other learning activities to try with generative AI tools.

The free version of NotebookLM is fairly generous. You can create up to 100 notes with up to 50 sources in each. Those sources can be up to 500,000 words or 200 megabytes. You can have 50 queries a day with your notebooks and create three audio overviews.

Doug Ward is associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications.

Microsoft and Adobe tools gain new AI functions

By Doug Ward

Teaching tools in Copilot

Microsoft has recently added Copilot tools specifically for teachers.

You will find the tools under the “Teach” link on the lower left toolbar in Copilot, Microsoft’s generative AI chatbot. (Make sure you log in with your KU credentials.) Here’s an overview of the new tools.

Lesson plan creator

You start by selecting a subject, a grade level (it has a setting for higher education), and an approximate time you want to spend on the lesson in class. You then provide information about the type of lesson or activity you want to create. That area allows up to 10,000 characters (1,500 to 2,000 words) for directions and background information. You can also upload a document for Copilot to work with. Once a draft has been created, you can edit it or direct Copilot to make changes. Once you are happy with the plan, you can save it to OneDrive as a Word document.

Rubric creator

Set a grade level and provide a title and description of what the rubric will be used for. Again, it allows up to 10,000 characters, so you can provide a substantial amount of direction and information. Unless you specify the categories for the rubric, Copilot will provide suggestions. Once a rubric is generated, an editing tool allows you to revise, add, rearrange and expand the rubric. You can save the completed rubric to OneDrive as a Word document.

Quiz creator

Set a grade level and provide a description and the number of questions you want to include in a quiz. You can provide up to 10,000 characters of information for the quiz creator to draw on. You can also upload a document for Copilot to use. Copilot creates quizzes in Microsoft Forms, and I know of no way to connect them to the Canvas gradebook. That makes this a nonstarter for many instructors, although it can be used to create practice quizzes for students.

Flashcard creator

This allows you to add up to 50,000 characters of information (7,500 to 10,000 words) for Copilot to work with. You can also upload a document. Copilot will create flashcards that focus on terms and definitions, questions and answers, or multiple-choice questions. This is a tool aimed at students, who should have access it.

For those who work with K-12 students, the lesson plan creator, the rubric creator, and the quiz creator include a dropdown menu with a large number of standards. Those include academic standards for Kansas and Missouri.

Microsoft says it will add additional tools to Copilot Teach in the coming months.

New AI functions in Adobe Acrobat

The KU version of Adobe Acrobat now has access to some generative AI features.

Acrobat now connects to Adobe Express, its cloud design and image platform, allowing users to translate a PDF, edit and create images from text in the PDF, and use Express to design or redesign a document. (I struggle to see the value in redesigning a PDF, given that other formats are much more versatile for design, but I may be missing something.)

Adobe added generative AI to Acrobat months ago for summarizing and providing overviews of documents, asking questions of documents, and creating new materials based on the content of a PDF. KU has not activated those features, though.

The generative AI features Adobe just added are cloud-based, meaning Acrobat sends a document to its cloud platform rather than working with it locally.

Doug Ward is associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications.

What we are learning about generative AI in education

By Doug Ward

Research about learning and artificial intelligence mostly reinforces what instructors had suspected: Generative AI can extend students’ abilities, but it can’t replace the hard work of learning. Students who use generative AI to avoid early course material eventually struggle with deeper learning and more complex tasks.

On the other hand, AI can improve learning among motivated students, it can assist creativity, and it can help students accomplish tasks they might never have tried on their own.

Keep in mind that nearly all the research over the past three years focuses on AI integrated into current class structures and learning environments. We need that kind of research to help us in the short term. AI systems are becoming more capable, autonomous, and ubiquitous, though, and we must reimagine what and how we teach and how we assess learning. Until we do that, we will be forced to take repeated stop-gap measures that will be as frustrating as they are futile.

My advice: Keep an open yet critical mind as we learn how and where generative AI best fits into teaching and learning. Experiment with AI tools and consider how they might assist student learning and extend the abilities of those working in your field. Share what you are learning with colleagues. And remind students of the perils of substituting AI for thinking.

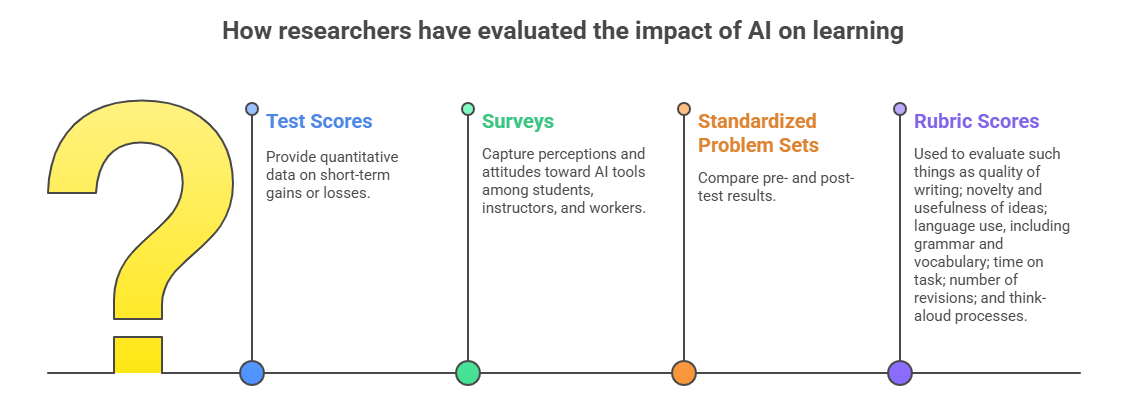

What follows is a breakdown of major themes in research into AI in education and workplaces. It reflects ideas from hundreds of studies across many disciplines. Findings are often contradictory or unclear, and varying definitions and approaches often make comparison difficult. Confounding that, a recent paper challenges the validity of much recent research into generative AI, saying that it is rushed and fails to separate the tool (generative AI) from pedagogical changes made when students use the tool.

Thinking, learning, and use of AI

Research into use of generative AI in education provides no single, clear recommendation. Some studies suggest that while AI tools can improve efficiency and accessibility, its overuse can diminish skills and critical thinking in the long run and potentially diminish empathy and creativity. Students who hand off foundational work to generative AI struggle when they try to complete later tasks, including coding, on their own. Psychologists call this avoidance of thinking “cognitive offloading” or “metacognitive laziness.” In one study, younger users of generative AI were prone to over-rely on AI tools for critical thinking.

Another study found lower brain connectivity among study participants who used generative AI for a writing project compared with those who used Google search or no assistance in writing. The lead author urged caution in interpreting the findings, though. Increased brain connectivity isn’t necessarily better, she said, and brain connectivity was higher among participants who used generative AI in later writing tasks. Two authors on that study were also part of another project in which an adaptive chatbot increased brain activity but not learning. A workplace study found a positive correlation between critical thinking and workers completing tasks on their own. Researchers also found that workers were more likely to engage in critical thinking when they were confident in completing tasks on their own. Thinking diminished when they relied too much on AI tools, a finding that is common among current literature.

One meta-analysis found that a vast majority of studies reported positive effects of generative AI on learning, motivation, and higher-order thinking. Most of those were in university-level classes in arts and humanities, health and medicine, or social sciences. Language education has gained considerable attention from researchers. Studies in that area suggest that the gains are the result of generative AI’s ability to provide personalized content, immediate access to information, diverse perspectives, and deeper perspectives on course material. Some researchers question the validity of some current research, though, saying it fails to account for whether use of generative AI improves student learning or whether high-performing students are more likely to use generative AI. Similarly, they question whether studies that suggest use of generative AI diminishes thinking have differentiated between AI tools and the skills of the students using the tool. One meta-analysis refers to this as a “directionality problem.” Studies of higher-order thinking often rely on students’ perceptions, the analysis says. The studies also focus on short-term gains (one to four weeks).

Another meta-analysis suggests that generative AI is most effective when used in problem-based learning, in courses where skills and competencies are well-defined, and in courses of four to eight weeks. It says, though, that integration of generative AI tools can improve higher-order thinking in nearly any course, largely because they provide constant feedback, guidance, and assessment, allowing students to reflect on their learning continually. One study also suggests that generative AI can improve higher-order thinking, especially in STEM courses. Researchers speculate that ChatGPT’s ability to explain complex topics in accessible language plays a role in that, allowing students to engage in a wider range of critical-thinking activities. Similarly, another study found that use of chatbots resulted in substantially improved understanding of medical terminology, and yet another study suggests that introduction of an AI tutor can help students develop skills for effective work in teams. A study of design students found that use of generative AI led to deeper analysis of sketches, broadened students’ scope of thinking about projects, supported complex problem-solving, and improved metacognition. Researchers said generative AI was a valuable collaborator in higher-order thinking. Another study found that engagement with chatbots could help reduce belief in conspiracy theories, even among people who whose beliefs were deeply held.

Other research suggests that students benefit most from generative AI when they already understand core concepts and have a clear sense of what they are trying to accomplish. One study argues that students’ use of generative AI tools for low-level tasks can skew their perceptions of the tools’ weaknesses and that helping them better understand those weaknesses can lead to better decisions. In terms of Bloom’s taxonomy, generative AI automates lower levels of the taxonomy by retrieving, organizing, and explaining information. Other researchers warn that repeated use of generative AI for higher-order tasks can create a dependency that diminishes students’ engagement in critical thinking. The title of a study summaries that line of research well: “ChatGPT is a Remarkable Tool – For Experts.” Even experts worry about overuse of generative AI, though. One programmer wrote about noticing his skills wane as he relied on Copilot. And in a recent hackathon pitting AI-assisted programming teams against teams working unaided, participants worried about being placed on non-AI teams. A team using generative AI won.

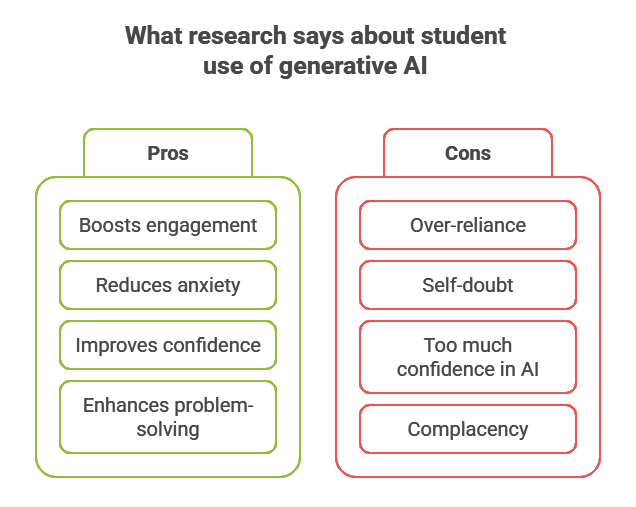

AI and student confidence

Some studies suggest that AI class assistants can improve student engagement and confidence, especially in handling complex problems. A survey by the Society of Industrial and Applied Mathematics suggests that use of AI can reduce students’ anxiety about math by providing personalized assistance and feedback. The survey also suggests that AI can improve student confidence in large classes. Others, though, say that use of generative AI can lead some students to question their academic abilities and feel reliant on AI for completing their coursework. Some of that may be related to a mismatch between self-confidence and individuals’ ability to evaluate the output of AI systems, one study suggests. Students need a better understanding of AI systems and their reliability, it and other studies argue. That understanding falls under an emerging approach called AI literacy, which can improve student confidence and innovative problem-solving skills.

The combination of student confidence and AI has other complexities. In one study, students were overly trusting of results from ChatGPT and less reflective than students who used electronic search to gather information. Microsoft researchers found that workers who had greater confidence in generative AI generally made less of an effort to evaluate, revise, analyze, or synthesize AI-generated content. Workers were less likely to evaluate chatbots critically when they were pressed for time or lacked the skills to improve the quality of AI output. Other studies suggest the same behavior. The Nielsen Norman Group calls this Magic 8 Ball Thinking, a reference to a toy that provides random answers when you turn it over. This type of thinking causes problems when people overestimate the capabilities of generative AI and become complacent in its use, especially if they use it in research outside their area of expertise and assume a response is accurate.

Chatbots and student success

A study involving physics students found that those who used a chatbot tutor at home scored considerably better on exams than students who were exposed to the same material in an interactive lecture. Those students also spent less time preparing for an exam and were more likely than their peers to take on challenging problems. Similarly, researchers have found that AI tools can be especially beneficial in self-directed learning, improving knowledge and skill development. Another study, though, found that student use of generative for studying resulted in lower grades. A meta-analysis suggests that generative AI can improve active participation in class activities, encourage experimentation and innovation, and improve emotional engagement if students feel less inhibited in asking assistance from a chatbot than they would their instructors. At Kennesaw State, a composition instructor found that student use of a chatbot connected to an open textbook improved the pass rate in composition classes and has helped “empower students to take ownership of their learning.”

Generative AI can be particularly helpful for students who are non-native English speakers or who have communication disabilities by providing tailored support and scaffolding. It helps translate text and explain complex ideas. It also allows students with weak language skills to improve their written work substantially. That includes large numbers of international students and students whose families don’t speak English at home. The improvements were greatest, though, among students with college-educated parents who had higher incomes. The researchers said the results suggested that those students had learned to use the technology well, not that they had improved their core skills. An analysis of discussion-board posts suggests that generative AI allowed students with weak language skills to improve their written work substantially, according to The Hechinger Report. That includes large numbers of international students and students whose families don’t speak English at home. The improvements were greatest among students with college-educated parents who had higher incomes. As Hechinger says, though, the results suggest that those students have learned to use the technology well, not that they have improved their core skills.

AI and creativity

Research on creativity and AI shows widely varying results, much like research into other aspects of generative AI. In some cases, generative AI can improve creativity in writing, a study in Science Advances suggests, and the work of writers who drew more ideas from AI was considered more creative than that of writers who used it for one idea or not at all. The downside, the researchers said, was that the stories in which writers used generative AI for ideas had a sameness to them, while those created solely by humans had a wider range of ideas. An MIT study similarly found that essays in which participants used generative AI were much more similar than those created by people who did not use AI.

Another study found that generative AI could decrease creativity in some circumstances. Novice designers who sketched by hand or drew inspiration from image searches created a wider variety of designs than those who used generative AI, and their work was judged more original. Yet another study is unambiguous, saying that students’ use of ChatGPT is detrimental to their creative abilities. A study involving design students, though, found that feedback from generative AI tools led to small improvements in students’ work.

In a comparison of humans and generative AI, a study from the Wharton School found that humans working alone produced a broader range of ideas for a new consumer product than ChatGPT did. The researchers said they identified prompting strategies to improve the diversity of ideas ChatGPT produced, though. Another study concluded that ideas from humans were more original and sophisticated than those produced by ChatGPT. The authors said, though, that generative AI could improve human creativity and innovation, in part by bringing in concepts from outside fields.

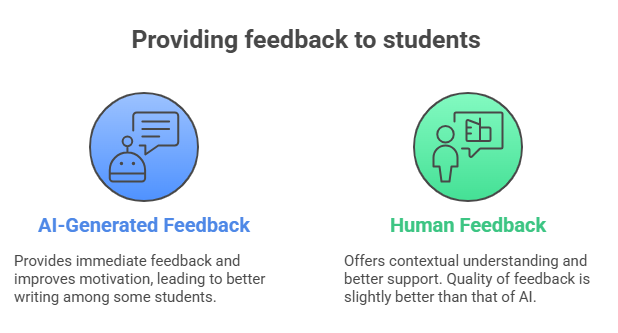

AI and feedback to students

The ability of generative AI to provide helpful feedback to students is one area where researchers generally agree – even as they urge caution. One recent study is among many suggesting that AI-generated feedback can help students improve their writing. One author of that study suggested, though, that the effect of AI-generated feedback might diminish as its novelty declines. A meta-analysis found that repeated rounds of AI-generated feedback led to improved student writing, mostly backing results of an earlier meta-analysis. Most of those studies compared the writing of students who received automated feedback with that of students who received no feedback. Two researchers of first-year writing courses, though, found that ChatGPT-produced feedback adhered to overly narrow criteria and often ignored prompts intended to guide it in working with more complex genre requirements.

Another study found that teachers provided better feedback on student writing than ChatGPT did, although the researchers said the differences were so small that they were nearly insignificant. Human evaluators understood the context of the student work and provided better feedback when students needed to include more supporting evidence, they said. It and other studies said, though, that the immediate feedback generative AI provided improved student motivation and engagement. Researchers say that educators should not assume that automated feedback will work for every student. It works best, they said, when combined with instructor feedback and other individual instruction.

In a study of videos and learning, researchers found that participants preferred human-created videos to AI-generated videos by a small margin. The study found no difference, though, in learning from either type of video, with researchers predicting that use of AI-generated video in education would proliferate as the technology improves. The study supported earlier research that an AI-generated avatar and the AI-generated voice of an instructor improved both motivation and learning among students.

What should we make of this?

The current research into generative AI in education provides insights but no clear direction, and things continue to change rapidly. We are learning a few things, though:

AI isn’t a replacement for learning. That may seem obvious, but students need to hear it frequently. Students have used generative AI to exploit the many weaknesses in our educational system: an emphasis on grades, a reliance on large classes, and a use of a handful of assessments as a means of determining success or failure, just to name a few. We need to build trust among students and we need to do a better job of helping them understand that learning takes time and effort and that occasional failure is an inevitable part of the process. For that to work, though, we must ensure that short-term failure can be turned into long-term success.

AI literacy is crucial. By this, I mean understanding how generative AI works, how it can be used effectively and ethically, why it is fraught with ethical issues, and how it is affecting jobs and society. Most students understand the downsides of substituting generative AI for their own thinking, and they want to learn more about it in their classes. They also have ideas for how instructors and institutions should handle generative AI (see the accompanying chart from Inside Higher Ed). We must provide opportunities to learn about generative AI in our courses, and discussions about its use should become a routine part of teaching.

We must find ways to use AI effectively. AI-provided feedback shows promise, and we need to keep experimenting with it and other approaches of integrating AI into teaching and learning. For example, how can it help students understand difficult concepts? How can instructors use it to adapt to students’ individual needs? How might it help instructors reenvision assignments? How can we create tools that help guide students when instructors aren’t available and that supplement learning? Those are just a few questions that many instructors and institutions are exploring.

There is no single ‘solution.’ I put “solution” in quotation marks because many faculty members seem to be looking for a policy, an approach, a method, an assessment design, a detector or something else that will “save” education from generative AI. There is no such thing. Rather, this is what some authors have described as a “wicked problem,” one with no single definition and no overarching solution. We must continue to experiment, weigh tradeoffs, and recognize that the changing nature of AI tools will force us to constantly adapt and iterate. Reflective teaching has become more important than ever.

Doug Ward is associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications.

AI trends that are shaping the future of education

By Doug Ward

A few eye-popping statistics help demonstrate the growing reach of generative AI:

- Use of ChatGPT has quadrupled in the past year, to 700 million weekly users. It has become the fifth-most-visited website.

- ChatGPT accounts for more than 80% of all chatbot sessions each month, followed by Copilot (9.5%), Perplexity (6.1%), and Gemini (2.7%).

- Nearly 90% of college students worldwide say they have used generative AI in their schoolwork.

Beneath the growing use of generative artificial intelligence lie many trends and emerging habits shaping the future of technology, jobs, and education. Social, political, and economic forces were already creating tectonic shifts beneath educational institutions. Generative AI has added to and accelerated the tremors over the past two and a half years, leaving many educators feeling angry and powerless.

Regardless of our views about generative AI, we must adapt. That will mean rethinking pedagogy, assignments, grading, learning outcomes, class structures, majors, and perhaps even disciplines. It will mean finding ways of integrating generative AI into assignments and helping students prepare to use AI in their jobs. That doesn’t mean all AI all the time. It does mean making skill development more transparent, working harder at building trust among students, and articulating the value of learning. It means having frequent conversations with students about what generative AI is and what it can and can’t do. It means helping students understand that getting answers from chatbots is no substitute for the hard work of learning. Importantly, it means ending the demonization of AI use among students and recognizing it as a tool for learning.

I’ll be writing more about that in the coming year. As a prelude, I want to share some of the significant trends I see as we head into year three of ChatGPT and a generative AI world.

Use of generative AI

Younger people are far more likely to use generative AI than older adults are. According to a Pew Research Center survey, 58% of 18- to 29-year-olds have used ChatGPT, compared with 34% of all adults. In late 2024, more than a quarter of 13- to 17-year-olds said they had used generative AI for schoolwork, Pew Research said. As teenagers make AI use a habit, we can expect them to continue that habit in college.

Young people have long been quicker to adopt digital technology than their parents and grandparents (and their teachers). They are less set in their ways, and they gravitate toward technology that allows them to connect and communicate, and to create and interact with media. Once again, they are leading changes in technology use.

AI use among college students is widespread

In a worldwide survey of college students, 86% said they had used AI in their studies, and many students say generative AI has become essential to their learning. In interviews and a focus group conducted by The Chronicle of Higher Education, students said they used AI to brainstorm ideas, find weak areas in their writing, create schedules and study plans, and make up for poor instruction.

Some students said they relied on AI summaries rather than reading papers or books, complaining that reading loads were excessive. Others rely on generative AI to tutor them because they either can’t make it to professors’ office hours, don’t want to talk with the professors, or don't think professors can help them. Some students also use ChatGPT to look up questions in class rather than participate in discussion. Some, of course, use generative AI to complete assignments for them.

That use of AI to avoid reading, writing, and discussion is frustrating for faculty members. Those activities are crucial to learning. Many students, though, see themselves as being efficient. We need to do a better job of explaining the value of the work we give students, but we also need to scrutinize our assignments and consider ways of approaching them differently. Integrating AI literacy into courses will also be critical. Students need – and generally want – help in learning how to use generative AI tools effectively. They also need help in learning how to learn, a skill they will need for the rest of their lives.

Most faculty have been skeptical of generative AI

Most instructors lack the time or desire to master use of AI or to make widescale changes to classes to adapt to student use of AI. A Pew poll suggests that women in academia are considerably more skeptical of generative AI than men are, and U.S. and Canadian educators are more skeptical of generative AI than their counterparts in other countries. Research also reinforces what was already apparent: Generative AI can impede learning if students use it to replace their thinking and engagement with coursework.

All of that has created feelings of resentment, helplessness, and a hardening of resistance. Some instructors say AI has devalued teaching. Others describe it as frightening or demoralizing. In a New York Times opinion piece, Meghan O’Rourke writes about the almost seductive powers of ChatGPT she felt as she experimented with generative AI. Ultimately, though, O'Rourke, a creative writing professor at Yale, described large language models as “intellectual Soylent Green,” a reference to the science fiction film in which the planet is dying and the food supply is made of people.

Educators are facing “psychological and emotional” issues as they try to figure out how to handle generative AI in their classes. I have seen this firsthand, although AI is just one of many other forces bearing down on faculty. I’ve spoken with faculty members who feel especially demoralized when students turn in lifeless reflections that were obviously AI-generated. "I want to hear what you think," one instructor said she had told her students. Collectively, this has led to what one educator called an existential crisis for academics.

Use of AI in peer review creeps upward

Some publishers have begun allowing generative AI to help speed up peer review and deal with a shortage of reviewers. That, in turn, has led some researchers to add hidden prompts in papers to try to gain more favorable reviews, according to Inside Higher Ed. A study in Science Advances argues that more than 13% of researchers in biomedical research used generative AI to create abstracts in 2024.

Use among companies continues to grow

By late 2024, 78% of businesses were using some form of AI in their operations, up from 55% in 2023. Many of those companies are shifting to use of local AI systems rather than cloud systems, in large part for security reasons. Relatedly, unemployment rates for new graduates have increased, with some companies saying that AI can do the work of entry-level employees. Hiring has slowed the most in information, finance, insurance, and technical services fields, and many highly paid white-collar jobs may be at risk. The number of internships has also declined. The CEO of Anthropic has warned that AI could lead to the elimination of up to half of entry-level white-collar jobs. If anything even close to that occurs, it will destroy the means for employees to gain experience and raise even more questions about the value of a college education in its current form.

Efforts to promote use of AI

Federal government makes AI a priority in K-12

The Department of Education has made use of AI a priority for K-12 education, calling for integration of AI into teaching and learning, creation of more computer science classes, and the use of AI to “promote efficiency in school and classroom operations,” improve teacher training and evaluation, and support tutoring. It mentions “AI literacy,” but implies that that means learning to use AI tools (which is only part of what students need). Technology companies have responded by providing more than $20 million to help create an AI training hub for K-12 teachers. The digital publication District Administration says education has reached “a turning point” with AI, as pressure grows for adoption of AI even as federal focus on ethics and equity has faded and federal guidelines do little to promote accountability, privacy, or data security. The push for more technology skills in K-12 comes as the growth in computer science majors at universities has stalled as students evaluate their job prospects amid layoffs at technology companies. That push also means that students are likely to enter college with considerable experience using generative AI in coursework, potentially deepening the conflicts with faculty if colleges and universities fail to adapt.

Canvas to add generative AI

Instructure plans to embed ChatGPT into Canvas soon. Instructure's announcement about this is vague, though not all that surprising, especially because Blackboard has added similar capabilities. Instructure calls the new functions IgniteAI, and its says they can be used for "creating quizzes, generating rubrics, summarizing discussions, aligning content to outcomes." It says these will be opt-in features for institutions. (A Reddit post provides more details of what Instructure demonstrated at its annual conference.) What this means for the KU version of Canvas isn’t clear, but the Educational Technology staff will be evaluating the new tools.

Google and OpenAI create tools for students and teachers

Google and OpenAI have offered tailored versions of their generative AI platforms for teachers and students. Google has added Gemini to its Google for Education tools and has released Gemini for Education, pitching it as transformative because of its ability to personalize learning and "inspire fresh ideas." The free version offers only limited access to its top models and Deep Research function, but the paid version, which is used primarily by school districts, has full access.

ChatGPT has created what it calls study mode for students. OpenAI says study mode takes a Socratic approach to help “you work through problems step by step instead of just getting an answer.” A PCWorld reviewer found the tool helpful, saying it "actually makes me use my brain." MIT Technology Review said, though, that it was “more like the same old ChatGPT, tuned with a new conversation filter that simply governs how it responds to students, encouraging fewer answers and more explanations.” It said the tool was part of OpenAI’s push “to rebrand chatbots as tools for personalized learning rather than cheating.”

AI companies see education as a lucrative market. By one estimate, educational institutions' spending on AI will grow by 37% a year over the next five years. Magic School, Curipod, Khanmigo, and Diffit are just four of many AI-infused tools created specifically for educators and students. That is important because student use in K-12 normalizes generative AI as part of the learning process.

To attract more students to ChatGPT, OpenAI made its pro version free for students for a few months in the spring. Google went even further, offering the pro version of Gemini free to students for a year. That means many students have access to more substantial generative AI tools than faculty do.

Social and technological trends

Online search is changing quickly

Nearly every search engine now uses generative AI to create summaries rather than providing lists of links. Those summaries usually cite only a small number of articles, and the chief executive of the Atlantic said Google was “shifting from being a search engine to an answer engine." As a result, fewer people are clicking on links to articles, and publishers report fewer visits to websites. News sites and other organizations that rely on advertising report substantial declines in web traffic. Bryan Alexander speculates that if this trend continues, we could see a decline in the web as an information source. The Wall Street Journal said companies’ use of generative AI was “rewiring how the internet is used altogether.” This poses yet another challenge for educators as students draw on AI summaries rather than working through articles and synthesizing information on their own.

Use of AI agents is spreading

Agents allow AI systems to act autonomously. They generally work in sequence (or in tandem) to complete a task. A controlling bot (a parent) sends commands to other bots (child systems), which execute commands, gather and check information, and either act on their own or push information back up the line for the parent bot to act.

Businesses have been cautious about deployment of agents, in part because of cost and security. Interest and spending have intensified, though, and companies have been using agents in such areas as customer service, inventory management, code generation, fraud detection, gene analysis, and the monitoring of digital traffic. One executive has said that software as a service was turning into "agent as a service."

Software companies have also made agent technology available to the public. OpenAI's agent can log into a learning management systems and complete assignments. Perplexity's new browser uses AI to search, summarize, and automate tasks, and it has been used to write in Google Docs in a way that mimics a human pace. ChatGPT agents can complete homework assignments autonomously, connect to other applications, log into websites, and even click on the human verification boxes that many websites put up. ChatGPT has also been used to automate grading and analyze teaching. The website Imaginative says companies are in a race to create agents that "organize your day without forcing you to switch apps.” Just how effective current agents are is open to debate, but the use of autonomous systems is growing.

Many children use AI for companionship

A vast majority of teenagers prefer human friendship over AI companions, but a third say that interacting with an AI companion is at least as satisfying as speaking with a human, according to Common Sense Media. An Internet Matters report says children as young as 9 use generative AI for companionship and friendship. They practice conversations, consult about what to wear, and ask questions about such things as feelings and body image. Some college students say that generative AI is diminishing relationships with other students.

Video games gaining AI capabilities

Video game makers are experimenting with generative technology that gives characters memories and allows them to adapt to game play. Stanford and Google researchers have added simulations of real people to games. Genie, a tool from Google's DeepMind division, creates an interactive world based on user prompts or images, and allows users to change characters and scenery with additional prompts. Similar approaches are already being used in educational technology, and it seems likely that we will eventually see AI characters act as teachers that can adapt to students’ work, voices, and even facial expressions as they guide students through interactive scenarios.

Audio, video, and image abilities improve

As the speed of AI models improves, AI companies see voice as a primary means of user interaction with chatbots. Already, the general AI models like ChatGPT, Gemini, Copilot, and Claude can analyze and create images and video, act on voice commands, and converse with users. Gemini will analyze information on a screen and provide advice on using and troubleshooting applications. A company called Rolling Square has created earbuds called Natura AI, which are the only means of accessing its AI system. Users interact with agents, which the company calls “AI people,” to do nearly anything that would usually require a keyboard and screen. A company called Rabbit has made similar promises with a device it released last year. It followed up this summer with an AI agent called Intern.

That is just one aspect of voice technology. More than 20% of online searches are done by voice, and the number of voice assistants being used has doubled since 2020, to 8.4 billion. Those include such tools as Alexa (Amazon), Siri (Apple), and Gemini (Google). The use of tools like Otter, Fireflies and Teams to monitor and transcribe meetings is growing, and it is common to see someone’s chatbot as a proxy in online meetings. Students are using transcription tools to record lectures, and use of medical transcription is growing substantially. Companies are using voice agents on websites and for customer service calls, and companies and governments are using voice as a means of digital verification and security.

- AI eyeglasses. Companies are creating eyewear with AI assistants embedded in them. The glasses translate text and spoken language, read and summarize written material, search the web, take photographs and record video, recognize physical objects, and connect to phones and computers. They usually contain a small display on one lens, and some can speak to you through bone conduction speakers. The trend toward miniaturization will make keeping technology out of the classroom virtually impossible.

- AI Audio. The capability of AI systems to generate audio and music continues to improve. Technology from ElevenLabs, for example, is used in call centers, educational technology, and AI assistants. It can clone voices, change voices, or create new voices. Google’s NotebookLM creates podcasts from text, audio and video files you give it, and other companies have begun offering similar capabilities. Tools like Suno and Udio create music from written prompts. Google’s assistant technology answers and screens calls on smartphones. AI is making the use of voice so prevalent that one blogger argues that we are returning to “an oral-first culture.”

So now what?

As use of generative AI grows among students, instructors must find ways to reimagine learning. That doesn't mean that everyone should adopt all things AI. As these trends indicate, though, the number of tools (and toys) that technology companies are infusing with AI is growing rapidly. Some of them offer promise for teaching and learning. Others will make cheating on traditional assignments easier and virtually impossible to detect. Adapting our classes will require experimentation, creativity, and patience. At CTE, we have many things planned (and already available) to help with that process, and we will continue to develop materials, provide examples, and help faculty adapt. We see opportunities for productive change, and we encourage instructors to join us.

Doug Ward is associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications.

How a new Copilot tool might be used in teaching

By Doug Ward

The KU version of Copilot now allows the creation of agents, which means you can customize Copilot and give it instructions on what you want it to do, how you want it to respond, and what format its output should follow.

An agent still uses Copilot’s foundational training, but the instructions can reduce the need for long, complex prompts and speed up tasks you perform regularly. You can also direct the agent to websites you would like it to draw on, and create starter prompts for users.

Copilot has also gained another function: the ability to store prompts for reuse. That isn’t nearly as useful as creating agents, but both additions give users additional control over Copilot and should make it more useful for many faculty members, staff members, and graduate students. (I don’t know whether the new functions are available to undergraduates, but they probably are.)

These features have been available for some time in paid versions of Copilot. What is new is the access available when you use your KU credentials to log in to Copilot, which is Microsoft’s main generative artificial intelligence tool.

Potential and limitations

Agents have the potential to improve the accuracy of responses of Copilot because the directions you provide limit the scope of Copilot’s actions and tailor the tone and substance of those responses. Accuracy also improves if you give Copilot examples and specific material to work with (an uploaded document, for instance).

If you log in with your KU ID, Copilot also has additional layers of data protection. For instance, material you use in Copilot isn’t used for training of large language models. It is also covered by the same privacy protections that KU users have with such tools as Outlook and OneDrive.

In addition to potential, Copilot has several limitations. Those include:

- Customization restrictions. A Copilot agent allows you to provide up to 8,000 characters, or about 1,500 words, of guidance. That guidance is essentially an extended prompt created with natural language, but it includes any examples you provide or specific information you want your agent to draw on. The 8,000 characters may seem substantial, but that count dwindles quickly if you provide examples and specific instructions.

- Input restrictions. Once you create an agent, Copilot also has an input limit of 8,000 characters. That includes a prompt and whatever material you want Copilot to work with. If you have given your agent substantial instructions, you shouldn’t need much of a prompt, so you should be able to upload a document of about 1,500 words, a spreadsheet with 800 cells, or a PowerPoint file with eight to 16 slides. (Those are just estimates.) The limit on code files will vary depending on the language and the volume of documentation and comments. For instance, Python, Java and HTML will use up the character count more quickly. The upshot is that you can’t use a Copilot agent to analyze long, complex material – at least in the version we have at KU. (The 8,000-character limit is the same whether you use an agent or use a prompt with Copilot itself.)

- Limit in scope. Tools like NotebookLM allow you to analyze dozens of documents at once. I haven’t found a way to do that with a Copilot agent. Similarly, I haven’t found a way to create a serial analysis of materials. For instance, there’s no way to give Copilot several documents and ask it to provide individual feedback on each. You have to load one document at a time, and each document must fall within the limits I list above.

- Potential fabrication. The guidance you provide to a Copilot agent doesn’t eliminate the risk of fabrication. All material created by generative AI models may include fabricated material and fabricated sources. They also have inherent biases because of the way they are trained. It is crucial to examine all AI output closely. Ultimately, anything you create or do with generative AI is only as good as your critical evaluation of that material.

An example of what you might do

I have been working with the Kansas Law Enforcement Training Center, a branch of KU that provides training for officers across the state. It is located near Hutchinson.

One component of the center’s training involves guiding officers in writing case reports. Those reports provide brief accounts of crimes or interactions an officer has after being dispatched. They are intended to be factual and accurate. At the training center, officers write practice reports, and center staff members provide feedback. This often involves dozens of reports at a time, and the staff wanted to see whether generative AI could help with the process.

Officers have the same challenges as all writers: spelling, punctuation, grammar, consistency, and other structural issues. Those issues provided the basis for a Copilot agent I created. That agent allows the staff to upload a paper and, with a short prompt, have Copilot generate feedback. A shareable link allows any of the staff members to use the agent, improving the consistency of feedback. The agent is still in experimental stages, but it has the potential to save the staff many hours they can use for interacting with officers or working with other aspects of training. It should also allow them to provide feedback much more quickly.

Importantly, the Copilot agent keeps the staff member in control. It creates a draft that the staff member can edit or expand on before providing feedback to the officer. That is, Copilot provides a starting point, but the staff members must draw on their own expertise to evaluate that output and decide what would be useful to the officer.

Other potential uses

If you aren’t sure whether you could use a Copilot agent in your teaching-related work, consider how you might use a personal assistant who helps with your class. What areas do students struggle with? What do they need help with when you aren’t available? What do they need more practice with? How can you help students brainstorm and refine ideas for projects and papers? What aspects of your class need to be re-envisioned? What tasks might you give an assistant to free up your time?

For instance, a CTE graduate fellow hopes to create an agent to help students learn MLA and APA style. I have written previously about how Copilot can be used as a coach for research projects. Many faculty members at the University of Sydney have created agents for such tasks as tutoring, skill development, and feedback to students. Their agents have been used to help students in large classes prepare for exams; help faculty create case studies and provide feedback on student work; help students troubleshoot problems, improve grammar skills, practice interviewing, better understand lecture content, create research proposals, and get answers to general questions about a class when an instructor isn’t available. Those faculty members are in fields such as biology, occupational therapy, biochemistry, education, social work, psychology, nursing, and journalism.

Some of the examples at the University of Sydney may be difficult for KU faculty to emulate because Sydney has a custom-built system called Cogniti. That system uses Copilot agents but has more sophisticated tools than KU has. Microsoft has also created many types of agents. As with the examples from Sydney, some are beyond the capabilities of the system we have access to at KU, but they can give you a sense of what is possible.

If you decide to create your own agent, I explain in a separate article and video how you can do that. My goal is to help instructors explore ways to use generative artificial intelligence proactively rather than feel like they are constantly fighting against its misuse. If nothing else, creating guidance for an agent can help you better articulate steps students can take to improve their learning and identify areas of your class you might want to improve.

Doug Ward is associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications.

Surveys suggest a steep, rocky hill ahead for education's adaptation to AI

By Doug Ward

Adapting colleges and universities to generative artificial intelligence was never going to be easy. Surveys released over the past two weeks provide evidence of just how difficult that adaptation will be, though.

Here’s a summary of what I'm seeing in the results:

Faculty: We lack the time, understanding, and resources to revamp classes to an AI age. A few of us have been experimenting, but many of us don’t see a need to change.

Administrators: We think generative AI will allow our institutions to customize learning and improve students' research skills, but we need to make substantial changes in teaching. We are spending at least some time and money on AI, but most of our institutions have been slow to adapt and aren’t prepared to help faculty and staff gain the skills and access to the tools they need.

That’s oversimplified, but it captures some of the broad themes in the surveys, suggesting (at least to me) a rocky path over the coming years. And though the challenges are real, we can find ways forward. From what I'm seeing in the surveys, we need to help instructors gain experience with generative AI, encourage experimentation, and share successes. We also need to do a better job of defining AI, generative AI, and use of AI, especially in class policies and institutional guidance. The surveys suggest considerable confusion. They also suggest a need to move quickly to help students gain a better understanding of what generative AI is, how it can be used effectively, and why it has many ethical challenges associated with it. In most cases, that will require a rethinking of how and what we teach. We have provided considerable guidance on the CTE website, and we will continue to explore options this spring.

Some of the more specific results from the surveys can help guide us toward the areas that need attention.

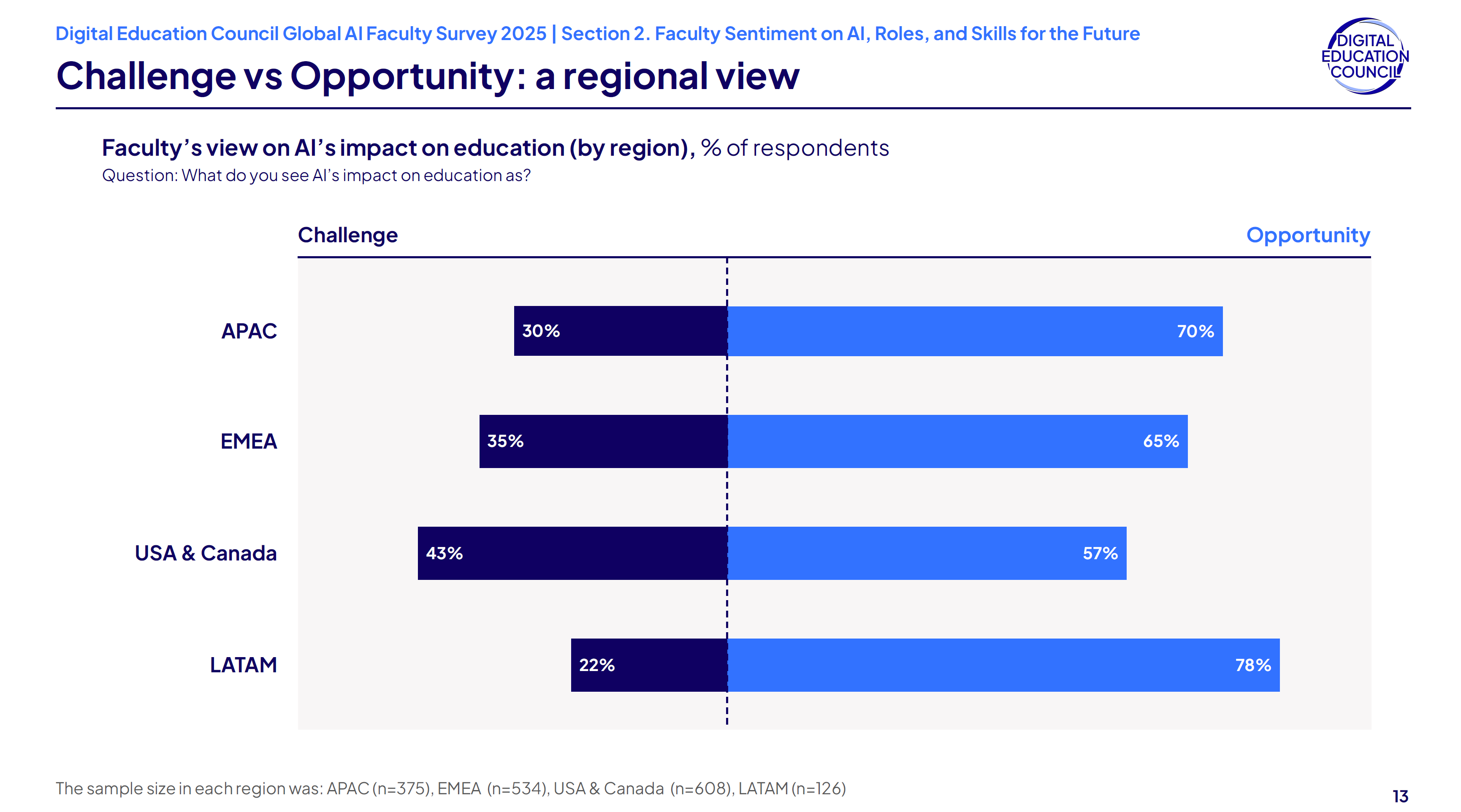

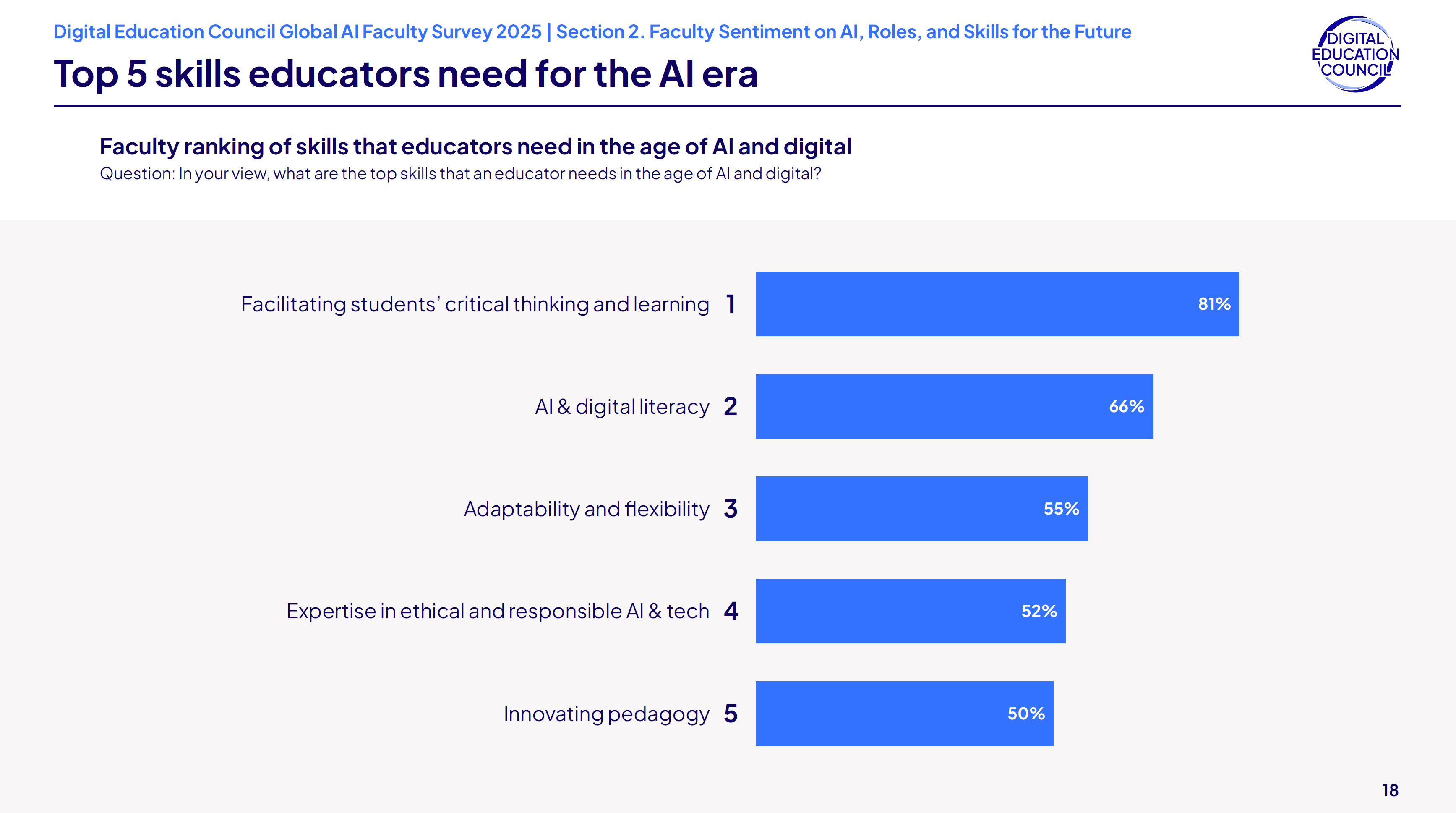

U.S. educators see AI differently from their global counterparts

Faculty in the United States and Canada view generative AI in a far gloomier way than their colleagues in other countries, a survey from the Digital Education Council suggests. They are far more likely to say that generative AI is a challenge and that they will not use it in their teaching in the future.

Worldwide, 35% of the survey’s respondents said generative AI was a challenge to education and 65% said it was an opportunity. Regionally, though, there were considerable differences, with 43% of faculty in the U.S. and Canada calling AI a challenge compared with 35% in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa; 30% in the Asia Pacific region, and 22% in Latin America.

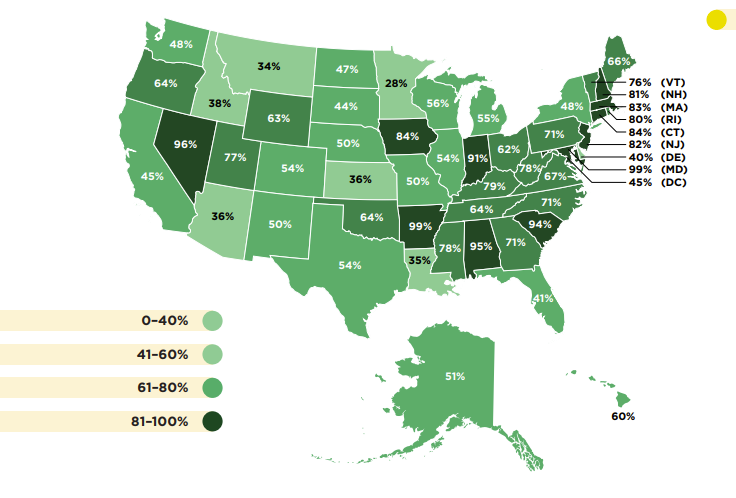

Similarly, a much greater percentage of faculty in the U.S. and Canada said they did not expect to use AI in their teaching in the future. Looked at another way, 90% to 96% of faculty in other regions of the world said they expected to integrate AI into their classes, compared with 76% in the U.S. and Canada.

Alessandro Di Lullo, chief executive of the Digital Education Council, said in a briefing before the survey results were released that faculty skepticism in the U.S. and Canada surprised him. Historically, he said, instructors in both countries have had “propensity towards innovation and more openness towards innovation.”

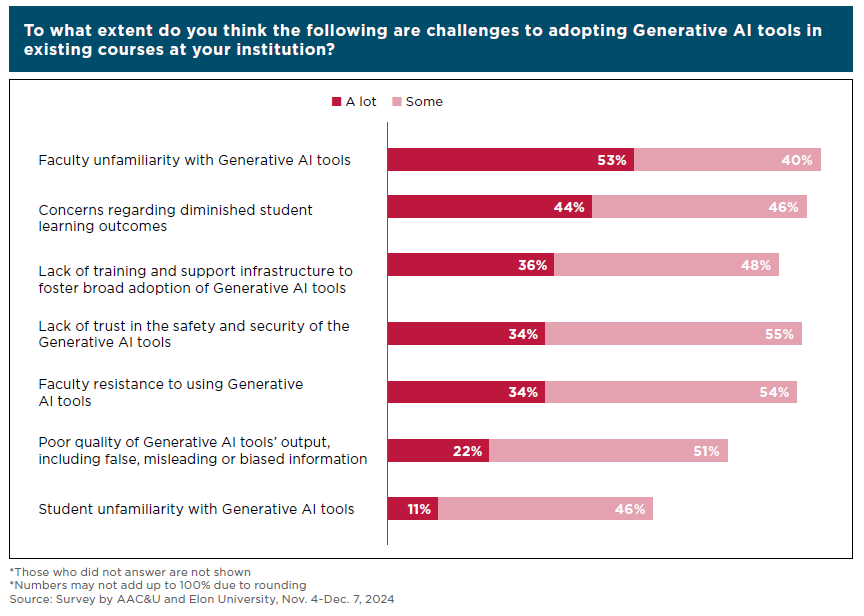

AAC&U survey suggests need but little momentum

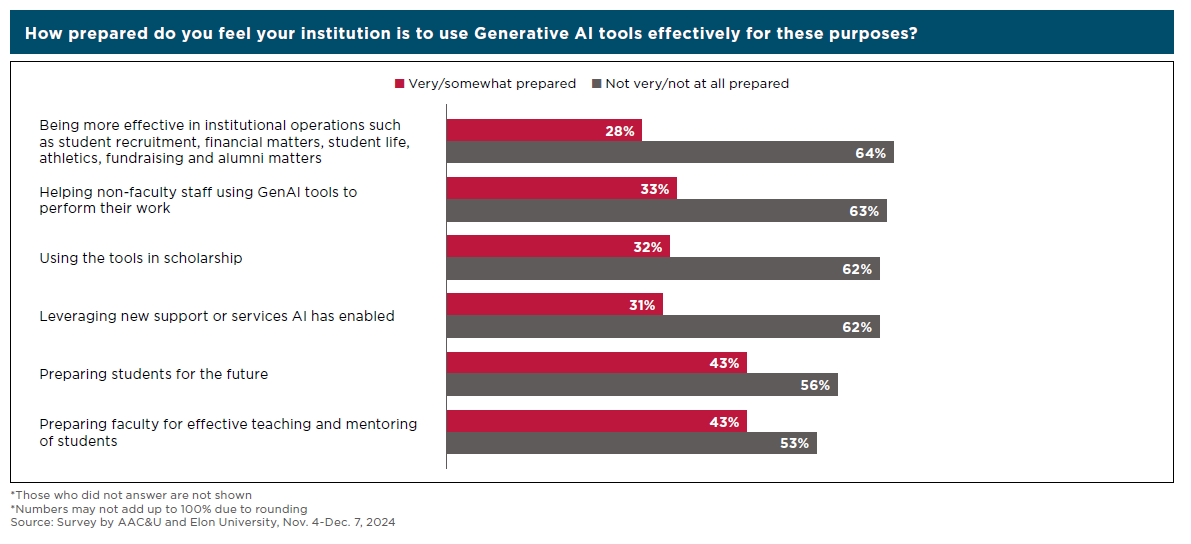

A survey released this week by the Association of American Colleges and Universities and Elon University offered a similarly sober assessment of U.S. higher education’s handling of generative AI. That survey included only university leaders, with large percentages saying their institutions weren’t prepared to help faculty, students, or staff work with generative AI even though they anticipate a need for substantial change.

Leaders of small colleges and universities expressed more concern than those at larger institutions. Eighty-seven percent of leaders at small institutions (those with fewer than 3,000 students) said that preparing faculty to guide students on AI was a key challenge, compared with 51% to 54% at larger institutions. Leaders said the biggest challenges included faculty’s lack of familiarity with – and resistance to – generative AI tools; worries that AI will diminish student learning; lack of training and infrastructure to handle generative AI; and security.

“Use of these tools is an attack on everything we do,” one leader said in the survey.

Most leaders said they were concerned about academic integrity, student reliance on AI tools, and digital inequities, but they also said generative AI would enhance learning and improve student skills in research and writing, along with creativity. Among leaders at institutions with 10,000 or more students, 60% said they expected the teaching model to change significantly in the next five years to adapt to generative AI.

Most leaders see a need for some immediate changes, with 65% saying that last year's graduates were not prepared to work in jobs that require skills in generative AI.

Figuring out the role of generative AI in teaching

In the Digital Education Council survey, 61% of faculty respondents said they had used generative AI in their teaching, although most reported minimal to moderate use, primarily for creating class material but also for completing administrative tasks, helping students learn about generative AI, engaging students in class, trying to detect cheating, and generating feedback for students.

Of the 39% of respondents who said they didn’t use generative AI, reasons included lack of time, uncertainty about how to use it in teaching, and concern about risks. Nearly a quarter said they saw no clear benefits of using generative AI.

That tracks with what I have seen among faculty at KU and at other universities. Many see a need for change but aren't sure how to proceed. Most have also struggled with how to maintain student learning now that generative AI can be used to complete assignments they have developed over several years.

Danny Bielik, president of Digital Education Council, said in a briefing that administrators needed to understand that many instructors were struggling to see the relevance of generative AI in their teaching.

“It's a wake-up call and a reminder to institutional leadership that these people exist, they're real, and they also need to be brought along for the journey if institutions are starting to make decisions,” Bielik said.

'The role of humans is changing'

Other elements of the survey tracked along familiar lines:

- Views of AI. 57% of respondents said they had a positive view of AI in education and 13% had a negative view. The rest were somewhere in between.

- Roles of instructors. 64% said they expected the roles of instructors to change significantly because of generative AI; 9% expected minimal or no change. Relatedly, 51% said AI was not a threat to their role as an instructor, and 18% said their role was threatened. Those who considered themselves more proficient with generative AI were more likely to say that teaching would need to adapt.

- AI as a skill. Two-thirds of respondents said it was important to help students learn about generative AI for future jobs. Even so, 83% said they were concerned about students’ ability to evaluate the output of chatbots, with a similar percentage saying they worried about students becoming too reliant on AI.

- Use of AI in class: 57% of faculty surveyed said they allowed students to use generative AI on assignments as long as they followed instructor stipulations and disclosed its use; 23% said no AI use was permitted, and 11% said AI use was mandatory.

Di Lullo said he was surprised by some of the results, especially because “the role of humans is changing” and colleges and universities need to adapt.

Bielik said the survey results were a “very good indication that there are people not necessarily sitting on the fence, but they're not paying as much attention to it as we are.”

Yet another recent poll supports that observation. Just a few days after the Digital Education Council survey was released, a Gallup poll said that that nearly two-thirds of Americans didn't realize they were already using AI-infused technology. That technology includes such things as assistant software like Siri and Alexa, navigation software, weather apps, social media, video streaming, and online shopping. Overall, Gallup said, Americans tend to see generative AI in negative terms, with young adults (age 18 to 29) expressing the highest percentage of concern about its impact. Three-fourths of young adults said they were especially worried about job prospects as use of generative AI grows. Those of all ages who know about AI’s integration into existing technology view it more positively.

As we rethink our teaching, we need to build community and trust among students and encourage them to help us find a way forward. We also need to help students understand how the skills they gain in college will help them become more adaptable to change. First, though, we need to adapt ourselves.

***********************************

Doug Ward is associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications.

Some thoughts about generative AI as the semester starts

By Doug Ward

The shock has worn off, but the questions about how to handle generative artificial intelligence in teaching and learning seem only to grow.

Those questions lack easy answers, but there are concrete steps you can take as we head into the third year of a ChatGPT world:

- Create a clear policy about generative AI use in your class.

- Talk with students about generative AI frequently. Encourage questions.

- Talk frequently about the skills students gain in your class. Explain why those skills are important and how students can use them. Do this early in the semester and then with each assignment.

- Build community and trust in your classes. Student use of generative AI is a symptom of underlying issues of trust, perceptions of value, and social pressures, among other things.

- Create assignments that help students explore generative AI. You don't have to like or promote generative AI, but students need to understand its strengths and weaknesses, and how to approach its output with a critical eye.

- Experiment with generative AI yourself and consider how it is – or might – change your discipline and your teaching.

That’s just a start. As I said, the questions about generative AI keep piling up. Here are a few additional updates, thoughts, and observations.

What is the university doing with AI?

Several things have been taking place, and there are many opportunities to learn more about generative AI.

- AI Task Force. A task force that includes members of the Lawrence and medical school campuses began work in the fall. It will make recommendations on how the university might approach generative AI. It will then be up to university leaders and faculty and university governance to decide what types of policies (if any) to pursue.

- Faculty Senate and University Senate. Both governance bodies have had discussions about generative AI, but no formal policies have emerged.

- University bot. The university has contracted with a vendor to provide a chatbot for the KU website. The bot is still being developed, but vendor interviews focused on such uses as interacting with prospective students, responding to text queries from students, providing reminders to students, and answering questions related to IT and enrollment management.

- AI in Teaching Working Group. This group, through the Center for Teaching Excellence, meets monthly online, and it has a related Teams site. If you are interested in joining either, email Doug Ward (dbward@ku.edu).

- AI think tank. Lisa Dieker (lisa.dieker@ku.edu) has organized the AI Tech User Think Tank through the FLITE Center in the School of Education and Human Sciences. It is intended primarily for connecting faculty interested in AI-related grant work and research, but meetings cover many types of AI-related issues. Contact her if you are interested in joining.

- Digital Education Council. The School of Education and Human Sciences has joined the Digital Education Council, an international group of universities and corporations focused on collaborative innovation and technology. Much of the group’s recent work has focused on use of generative AI in education and industry.

- Libraries AI discussion group. The KU Libraries staff has been actively exploring how generative AI might change the way people search, find, and use information. A Teams discussion site has been part of that. Most conversations are, of course, library related, but participants often share general information about AI or about library trials.

- CTE AI course. CTE has made AI-related modules available for instructors to copy, use, or adapt in their own courses. The modules cover such areas as how generative AI works, why it creates many ethical quandaries, how it can be used ethically, and what the future of AI might entail. Anyone interested in gaining access to the modules should email Doug Ward (dbward@ku.edu).

What about a policy for classes?

The university has no policy related to AI use in classes, and we know of no policy at the school level, either. That means it is crucial for instructors to talk with students about expectations on AI use and to include syllabus information about use of, or prohibitions on, generative AI.

We can’t emphasize that enough: Talk with students about generative AI. Encourage them to ask questions. Make it clear that you welcome those questions. No matter your policy on use of generative AI, help students understand what skills they will gain from your class and from each assignment. (See Maintaining academic integrity in the AI era.)

What are we hearing about AI use among students?

Students have been conflicted about generative AI. Some see use of it as cheating. Some view the training of generative AI on copyrighted material as theft of intellectual property. Some worry about privacy and bias. Others worry about AI’s environmental impact.

Even so, large percentages of students say they use generative AI in their coursework, even if instructors ask them not to. They expect faculty to adapt to generative AI and to help them learn how to use it in jobs and careers. For the most part, that hasn’t happened, though.

Most students welcome the opportunity to talk about generative AI, but many are reluctant to do so out of fear that instructors will accuse them of cheating. That has to change. Only by engaging students in discussions about generative AI can we find a way forward.

Why are so many students using generative AI?

Many instructors assume students are lazy and want to cheat. The reality is far more complex. Yes, some avoid the hard work of learning. Most, though, use generative AI for other reasons, which include the following:

- Students feel unprepared. Many students struggled during the pandemic. Expectations of them diminished, and many never gained the core reading, writing, math, and analytical skills they need in college. College requirements and expectations have largely remained the same, though, with students unsure how to cope. Generative AI has become a way to make up for shortcomings.

- They feel overwhelmed. Some students have families or other obligations, many work 20 or more hours a week, and most still feel lingering effects from the pandemic. Anxiety, depression, and related mental health issues have increased. That mix pushes many students to take shortcuts just to get by.

- They feel pressured to achieve high GPAs. Scholarships often require a 3.5 GPA or higher, and students who want to attend graduate school or medical school feel a need to maintain high GPAs. That can push them toward AI use if they fear falling below whatever benchmark they have set for themselves or that others have imposed on them.

- They lack skills in time management. Students who wait until the last minute to study or to complete assignments create unnecessary stress for themselves. They also find out that assignments can’t be completed at the last minute, and they turn to AI for help.

- They worry about job expectations. Students have been getting mixed messages about generative AI. Some instructors denounce it and see any use of it as cheating. At the same time, many employers say they expect graduates to know how to use it. Current students are especially job-oriented. Depending on what they hear and read, they may see experience with generative AI as more important than skills they would gain by doing coursework themselves.

- They see a degree as a consumer product. As the cost of college has increased, many students have started looking at a degree in transactional terms. A degree is simply a means to a job. They are paying a lot of money, the reasoning goes, and that should give them the right to use whatever tools they want to use and to approach class in whatever way helps them succeed.

- They don’t see value in an assignment or class. This is a big aspect of most types of academic misconduct. Most students want to learn, but they don’t always understand why they must take particular classes or complete some assignments. If students don’t see value in an assignment or a class, they may just turn over any work to generative AI.