By Doug Ward

We need to talk.

Yes, the conversation will make you uncomfortable. It’s important, though. Your students need your guidance, and if you avoid talking about this, they will act anyway – usually in unsafe ways that could have embarrassing and potentially harmful consequences.

So yes, we need to talk about generative artificial intelligence.

Consider the conversation analogous to a parent’s conversation with a teenager about sex. Susan Marshall, a teaching professor in psychology, made that wonderful analogy recently in the CTE Online Working Group, and it seems to perfectly capture faculty members’ reluctance to talk about generative AI.

Like other faculty members, Marshall has found that AI creates solid answers to questions she poses on assignments, quizzes, and exams. That, she said, makes her feel like she shouldn't talk about generative AI with students because more information might encourage cheating. She knows that is silly, she said, but talking about AI seems as difficult as talking about condom use.

It can, but as Marshall said, we simply must have those conversations.

Sex ed, AI ed

Having frank conversations with teenagers about sex, sexually transmitted diseases, and birth control can seem like encouragement to go out and do whatever they feel like doing. Talking with teens about sex, though, does not increase their likelihood of having sex. Just the opposite. As the CDC reports: “Studies have shown that teens who report talking with their parents about sex are more likely to delay having sex and to use condoms when they do have sex.”

Similarly, researchers have found that generative AI has not increased cheating. (I haven't found any research on talking about AI.)

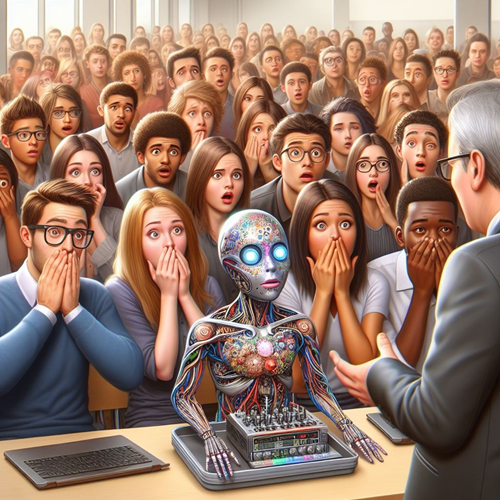

That hasn't assuaged concern among faculty members. A recent Chronicle of Higher Education headline captures the prevailing mood: “ChatGPT Has Everyone Freaking Out About Cheating.”

When we freak out, we often make bad decisions. So rather than talking with students about generative AI or adding material about the ethics of generative AI, many faculty members chose to ignore it. Or ban it. Or use AI detectors as a hammer to punish work that seems suspicious.

All that has done is make students reluctant to talk about AI. Many of them still use it. The detectors, which were never intended as evidence of cheating and which have been shown to have biases toward some students, have also led to dubious accusations of academic misconduct. Not surprisingly, that has made students further reluctant to talk about AI or even to ask questions about AI policies, lest the instructor single them out as potential cheaters.

Without solid information or guidance, students talk to their peers about AI. Or they look up information online about how to use AI on assignments. Or they simply create accounts and, often oblivious and unprotected, experiment with generative AI on their own.

So yes, we need to talk. We need to talk with students about the strengths and weaknesses of generative AI. We need to talk about the ethics of generative AI. We need to talk about privacy and responsibility. We need to talk about skills and learning. We need to talk about why we are doing what we are doing in our classes and how it relates to students’ future.

If you aren’t sure how to talk with students about AI, draw on the many resources we have made available. Encourage students to ask questions about AI use in class. Make it clear when they may or may not use generative AI on assignments. Talk about AI often. Take away the stigma. Encourage forthright discussions.

Yes, that may make you and students uncomfortable at times. Have the talk anyway. Silence serves no one.

JSTOR offers assistance from generative AI

Ithaka S+R has released a generative AI research tool for its JSTOR database. The tool, which is in beta testing, summarizes and highlights key areas of documents, and allows users to ask questions about content. It also suggests related materials to consider. You can read more about the tool in an FAQ section on the JSTOR site.

Useful lists of AI-related tools for academia

While we are talking about Ithaka S+R, the organization has created an excellent overview of AI-related tools for higher education, assigning them to one of three categories: discovery, understanding, and creation. It also provides much the same information in list form on its site and on a Google Doc. In the overview, an Ithaka analyst and a program manager offer an interesting take on the future of generative AI:

These tools point towards a future in which the distinction between the initial act of identifying and accessing relevant sources and the subsequent work of reading and digesting those sources is irretrievably blurred if not rendered irrelevant. For organizations providing access to paywalled content, it seems likely that many of these new tools will soon become baseline features of their user interface and presage an era where that content is less “discovered” than queried and in which secondary sources are consumed largely through tertiary summaries.

Preparing for the next wave of AI

Dan Fitzpatrick, who writes and speaks about AI in education, frequently emphasizes the inevitable technological changes that educators must face. In his weekend email newsletter, he wrote about how wearable technology, coupled with generative AI, could soon provide personalized learning in ways that make traditional education obsolete. His question: “What will schools, colleges and universities offer that is different?”

In another post, he writes that many instructors and classes are stuck in the past, relying on outdated explanations from textbooks and worksheets. “It's no wonder that despite our best efforts, engagement can be a struggle,” he says, adding: “This isn't about robots replacing teachers. It's about kids becoming authors of their own learning.”

Introducing generative AI, the student

Two professors at the University of Nevada-Reno have added ChatGPT as a student in an online education course as part of a gamification approach to learning. The game immerses students in the environment of the science fiction novel and movie Dune, with students competing against ChatGPT on tasks related to language acquisition, according to the university.

That AI student has company. Ferris State University in Michigan has created two virtual students that will choose majors, join online classes, complete assignments, participate in discussion boards, and gather information about courses, Inside Higher Ed Reports. The university, which is working with a Grand Rapids company called Yeti CGI on developing the artificial intelligence software for the project, said the virtual students’ movement through programs would help them better understand how to help real students, according to Michigan Live. Ferris State is also using the experiment to promote its undergraduate AI program.

Doug Ward is associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications.

Tagged artificial intelligence, future of higher education, student skills, teaching and technology