Seeing through education to find learning

At workshops for graduate teaching assistants on Monday, I shared one of my favorite quotes about education.

It’s from Joi Ito, director of MIT’s Media Lab. In a TED Talk on innovation last year, he said: “Education is what people do to you. Learning is what you do to yourself.”

He added, “What you need to learn is how to learn.”

Several students took issue with Ito’s premise of “education” as something imposed on students. They should. It’s a generalization that pulls in all the negative perceptions people have about schools and higher education. It draws on imagery of education as a factory where students are slathered with information as they move along a conveyor belt and tested for uniformity before they emerge at the end of the line wrapped in a generic diploma that guarantees they will provide the “right” answer on cue.

And yet that’s Ito’s point. Learning is individual. It’s something you take on because you see value in it for yourself. Ito dropped out of college twice and is largely self-taught, experiences that most certainly shape his perspective on education but should also inform ours. As educators, we need to stress the importance learning rather than information. We must provide approaches to learning that are as rich and varied as our students, and create opportunities for students to find their own meaning and relevance in our curricula.

In my classes, I tell students that I can’t make them learn. I provide material to help them learn. I try to create a classroom environment where they feel welcome, and lead discussions that I hope will inspire them to learn – and keep learning. But I can do only so much. Students have to meet me halfway. They must complete the work I assign, share their ideas, and participate in discussions. They must invest in the process of learning. Only then will they truly learn.

continued in the hallways of Wescoe Hall during lunch.

Most GTAs understand that, I think. After all, by making their way to graduate school they have learned to work within – and thrive in – the current educational system. As they shift from students to instructors, they must unravel the concept of learning and help their own students put it back together. That’s a challenging mission, one they will spend the rest of their careers trying to perfect.

The GTAs in my sessions had a good sense of how to begin that mission. When I asked them to consider how we can help students learn how to learn, the group discussions were robust and enlightening. Here are some of the responses:

- Ask good open-ended questions and provide concrete examples that lead to meaty discussions.

- Provide a variety of examples that allow students to approach ideas from many angles.

- Provide a variety of ways for students to demonstrate understanding.

- Vary the method of instruction to help students learn in different ways.

- Model the behavior you want students to follow.

- Draw on your own experiences with learning and use those as relatable examples.

- Help students make connections between academic topics and life.

- Scaffold class material so that students work in increments toward mastery of a subject.

- Humanize yourself as an instructor, make yourself available, and provide consistency throughout the semester.

The students’ suggestions provide an excellent framework for classes of all types. I hope they left the sessions feeling as energized as I did about the possibilities not just of education, but of learning.

Why we need to stress learning, not information

Learning matters.

That may seem like a truism in the world of education – at least it should be – but it isn’t.

All too often, schools and teachers, colleges and professors worry more about covering the right material than helping students learn. They put information above application. They emphasize the what rather than the why and the how.

In an essay in Inside Higher Ed, Stephen Crew of Samford University makes an excellent case for the importance of learning. He does so with an anecdote about why instructors win teaching awards. For instance, the award-winners may have made sacrificed to pursue their teaching. They may have inspired students or made classes engaging. Perhaps their student evaluations were stellar.

Crew doesn’t dismiss those aspects of teaching. Rather, he says they are simply too shallow.

“The implication is that award-winning teachers are not any more effective at engendering student learning than the rest of us,” Crew writes. “Rather, they devote more time and attention to their teaching and students than we do, or they persevere through greater challenges.”

He asks – rightly – whether those instructors have really helped students learn.

Crew makes an important distinction between learning-driven teaching and information-driven teaching.

Learning-driven teachers help students challenge their thinking, including their metacognitive skills, and demonstrate the importance of deeper understanding. They provide meaningful opportunities for students to apply skills, and then assess students’ understanding and nudge them toward a goal.

Information-driven teaching, on the other hand, is a relatively straightforward affair than nearly anyone can do. It emphasizes accurate, up-to-date content; presentation style; and perhaps the newest technology. “In this approach, the teacher either cannot or should not influence learning beyond the method of delivering information,” Crew writes.

Instructors may be popular and passionate and engaging, Crew says, but if they simply deliver information to students, they haven’t really taught anything.

Angelique Kobler of the Lawrence Public Schools made much the same point last year, saying that if instructors don’t embrace the idea that today’s students learn differently from those even a few years ago, “we will become irrelevant.”

A question that Kobler asked when she spoke with the KU Task Force on Course Redesign still resonates:

Has teaching occurred if learning hasn’t?

Related: What does a learner-centered syllabus look like? (Via Faculty Focus.)

* * * * * * *

Follow-up: The ups and downs of Blackboard

It will be interesting to see how a sale of Blackboard might affect the positive changes I wrote about earlier this week.

Reuters reported on Tuesday that Providence Equity Partners, which owns Blackboard, is looking to sell the company for more than $3 billion. Blackboard, which was created in 1998, had been a public company until Providence bought it and took it private in 2011, paying $1.64 billion and assuming $130 million in debt.

To put the Blackboard price into perspective, here are a couple of comparisons: Forbes estimates the value of the New York Yankees at more than $3 billion. After an initial public offering, the online marketplace Etsy is worth more than $3 billion. So is Donald Trump.

A sale wouldn’t be surprising. Companies like Providence buy lagging companies, revamp them and try to sell them for a profit. Blackboard has become more responsive to customers since Providence took over and hired Jay Bhatt as president and CEO. And news of a possible sale comes just after the completion of Bb World, Blackboard’s annual conference, and the announcement of a slew of changes that would finally pull Blackboard’s design and functionality out of the dial-up web era.

My colleagues in IT say, though, that Blackboard’s promised design changes probably won’t be practical for most schools to adopt for two to three years. That’s because Blackboard is building a new platform for Learn, its learning management system. That new platform lacks many of the integration capabilities the current system has, including grading for discussion boards, integration with SafeAssign, and integration with university enrollment systems.

So adopting the new platform, called Ultra, may depend on how much schools are willing to give up in terms of integration to gain a system that looks and acts like the modern web. Adoption will become even trickier for schools as the company pursues a pricing strategy that resembles that of the automobile industry. A college or university pays one price for the basic Blackboard Learn platform, and then must decide on an array of add-ons that drive up expenses but that contain the most sought-after functions and tools.

For instance, a school has to pay extra for access to the new student app and for the updated instructor grading app. (I wrote on Tuesday that I couldn’t get those apps to work. That’s why.) Blackboard Collaborate requires an extra fee, as does the assessment tool and a host of other digital goodies.

So even as Blackboard promises many positive changes, it is still acting very much like the behemoth it is.

We interrupt this post to report on the teacher draft

That’s right. I said the teacher draft. The comedy team Key and Peele take an ESPN-like look at what the world of teaching might look like if it were elevated to the status of sports: the $80 million salaries, the No. 1 draft pick whose father “lived from paycheck to paycheck as a humble pro football player,” and the “teacher-of-the-year play” in the day’s highlights. If only.

Briefly …

A participant on the E-Learning Heroes discussion board set off a flurry of responses with this question: “Do learners really care about learning objectives?” Trina Rimmer offers a useful overview of the discussions that followed. … First-time smartphone users said their devices distracted from their learning even though they initially thought they would help, The Journal reports, citing a study from Rice University and the U.S. Air Force. … Personalized learning, which allows students to choose the direction and the pace of their learning, provides a critical means to engage at-risk students, Rebecca Wolfe tells The Hechinger Report. Wolfe is the director of the Students at the Center project, which is part of the nonprofit organization Jobs for the Future.

Blackboard announces some long-needed changes

I’ll be blunt: Blackboard Learn has all the visual appeal of a 1950s warehouse.

In terms of usability, it’s like trying to navigate an aircraft carrier when you really need a speedboat.

To Blackboard’s credit, it’s not that different from other learning management systems, which emphasize security and consistency from class to class as selling points. The company has been listening to user complaints, though, as upstarts like Canvas, Desire2Learn, and Moodle (in which Blackboard owns a stake) have chipped away at its dominant market share over the last few years.

Last week at BbWorld, the company’s annual conference, officials said that Blackboard Learn would get a much-needed facelift. It also announced changes in its Collaborate service and in its mobile apps.

Jim Chalex, a senior director for product management, said the changes in Blackboard Learn would focus not just on visual appeal but on ease of use both on PCs and mobile devices. (You can watch a recording of the session (There was a link here, but the page no longer exists), as I did, but you’ll need to register. It’s free.)

Chalex said the company wanted Blackboard Learn to look more like social media sites and other websites that students and faculty used regularly.

“Those are modern designs that are constantly unfolding and evolving and staying on the bleeding edge,” he said. “We want to be right there and to stay on that edge and to actually drive it, to innovate along with those. We think that leads to a more engaged learner.”

Within the next year, it plans to offer layered navigation (think of the site breaking into several vertical strips for you to choose from), the ability to drag and drop material from a computer’s desktop, easier access to analytics, and easier access to often-used tools. Keep in mind that access to those features will depend on each university’s adoption time.

In the future, it plans redesigned discussion boards and rubrics, better integration of audio and video, easier organization and use of groups, ability to create customized pages, improved integration of plagiarism detection, and better integration of material from outside publishers.

The company is calling these changes the “Blackboard Learn Ultra Experience.” (I’d call it “Blackboard: Beyond the Warehouse,” but no one asked me.)

The company has devoted a section of its website to the design changes it plans (There was a link here, but the page no longer exists), along with the philosophy behind them. It also has a page to sign up to try the technical preview (There was a link here, but the page no longer exists) of the coming changes.

Blackboard Collaborate

Blackboard says it has overhauled Collaborate, the software for interacting with students remotely, in both the look and technical framework.

The changes, it said, will allow for easier creation of virtual office hours, student study groups, and webinars. It will also allow for high-definition video and an ability to record sessions and publish them in .mp4 format for download.

Rather than opening stand-alone software, the new version of Collaborate “starts in the browser and stays in the browser,” said David Hastie, senior director for product management for Collaborate.

The new version of Collaborate is also responsive, meaning it will adapt easily to any type of device. It also adapts to the type of content being displayed and will allow for real-time closed captioning of live sessions. (This requires someone to listen and type the content.)

In future iterations, Collaborate plans better integration with Blackboard Learn, an ability to zoom in on content, revamped polling and breakout rooms, integration of teleconferencing, and an ability for instructors to load content in one session and have it remain for future sessions. Blackboard has also established a partnership with VoiceThread to allow for easier integration of that tool.

Mobile apps for Blackboard

In June, Blackboard announced the availability of a new mobile app called Bb Student.

Dan Loury, senior project manager for mobile, said at BbWorld that the student app was one of three apps that Blackboard was creating or updating. (The other two are for instructors and parents.)

The student app, available for iOS, Android or Windows Phone, creates a streamlined view of critical information for students, he said. This includes an “activity stream,” which is a bit like a to-do list of assignments and due dates, along with updates on comments and announcements. The app also provides an outline and timeline for all courses, access to the gradebook, and an ability to create assignments and take tests on mobile,

Blackboard says that future versions of the app will provide integration with Dropbox, OneDrive and Google Drive; an ability to activate push notifications; an ability to search within courses; and group collaboration with mobile devices, including virtual meetings with instructors or other students.

A faculty app, called Bb Grader (There was a link here, but the page no longer exists), has been available on iOS for some time. The last time I tried it, it lacked the ability to do the tasks I needed it to do. That has been some time, though. I downloaded it again this week but have not been able to get it or the student app to connect. Mobile versions of Blackboard Learn are also available, but I’ve found them dreadful, at least from an instructor standpoint.

All of the changes that Blackboard announced last week sound good, and I look forward to seeing them in action.

When I talk with faculty members about Blackboard Learn, I hear two common refrains: Make it easier to use, and make it more visually appealing. So despite my harsh comments about Blackboard, I applaud the company’s willingness to listen to faculty members and students, and to start modernizing the system. I just wish the changes hadn’t taken so long.

Lynda.com ends inexpensive student program

The online training site Lynda.com announced this week that it was canceling its lyndaClassroom program.

The classroom program allowed instructors to choose up to five online tutorials for students in a designated class to use during a semester. Students then signed up through Lynda.com and paid $10 a month, or about $35 for a semester.

It was an excellent, cost-effective way to help students gain technology skills. The cost was less than most textbooks, making it a useful tool for instructors in many fields.

Lynda offers nearly 4,000 training modules in everything from web development and design tools to photo, video, and audio creation. It began mostly as a site for technology training, and that training is still its mainstay. It has expanded its offerings over the last few years to include areas like business strategy, marketing, teacher training, and even grammar.

Lynda didn’t say why it was ending the program, although the company was acquired by LinkedIn earlier this year. Changes are inevitable after any acquisition.

In a brief email announcement, the company said the classroom program would end on July 17 “in order to focus our efforts on building even better experiences for educators and students.”

That sort of vapid corporate-speak usually means that prices will increase.

I had planned on using Lynda’s classroom program for a class this fall. I emailed Lynda’s customer support on Wednesday in hopes of finding out more about the changes. A representative emailed me back on Thursday saying that the company had been inundated with similar requests and would get back as soon as possible.

I certainly don’t begrudge Lynda’s desire to revamp its approach. I just wish the company had done a better job of communicating the changes and, ideally, had provided more time for educators to find other options.

Briefly …

A third of students in a recent poll said that anxiety about finances led them to neglect schoolwork, Money reports. About the same percentage said they had cut back on their class load because of financial worries. … A growing number of students see textbook purchases as optional even when professors say the books are required, The Chronicle of Higher Education reports.

New classrooms to help promote active learning

The School of Engineering at KU will open several new active learning classrooms this fall.

I’ve been involved in planning some of the summer training sessions for the rooms, so I’ve had a chance to explore them and see how they will work.

I’ve written before about the ways that room design can transform learning. Well-designed rooms reduce or eliminate the anonymity of a lecture hall. They promote discussions and learning by creating a sense of community. They make collaboration and sharing easy, and they allow instructors to move among students rather than just stand at the front and talk at them.

The new engineering rooms provide all of that. The 360-degree panorama above shows the largest of the rooms, which will hold 160 students. (Use the controls on the image to move around the room, or just press the “Ctrl” key on your computer and use the cursor to move around.) The new building also has a 120-seat classroom, a 90-seat classroom, and three 60-seat classrooms. You’ll find images of two of the smaller rooms below.

All the classrooms contain a key factor in active learning: tables that allow students to work in groups and that effectively shrink the room size. The tables in all of the rooms have wired connections so that individual students can project to their group or classroom screens with laptops, tablets or smartphones. They also have miniature Elmo document cameras.

The smaller classrooms have monitors at the ends of the tables; the 160-seat classroom has large-screen monitors on the walls, one for each table. The lecterns in all the rooms have large Wacom touch-screen tablets that will allow faculty members to draw on the screen, and most of the wall space consists of whiteboards.

Even the common spaces in the new building provide opportunities for learning. For instance, the atrium (see below) provides a marvelous gathering space for individual study but also for conversations that often lead to informal learning.

The creation of these rooms is a huge step forward in active learning. Six other classrooms in two other buildings will also open this fall. They won’t be as fancy as these rooms, but they reflect the reality that learning is changing and that learning spaces need to change, too.

Higher education’s tarnished image (part 2)

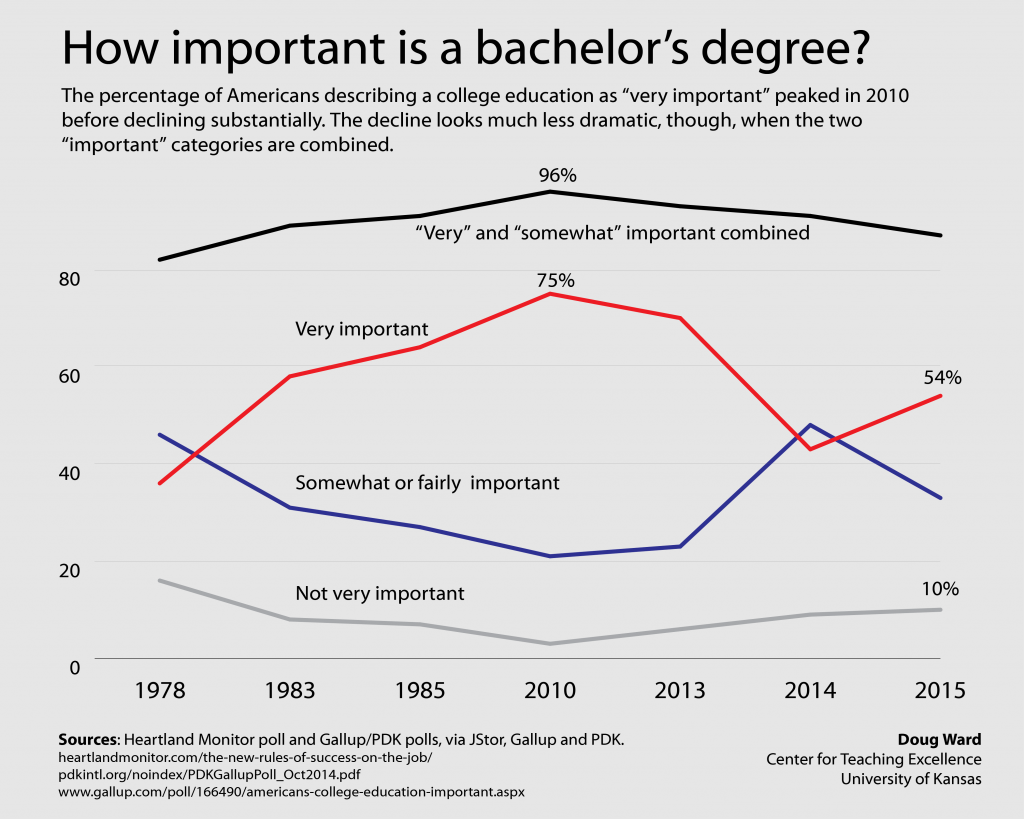

Most Americans still see a four-year degree as important, but it is not at the top of the list of things that will help someone achieve a successful career, a recent Heartland Monitor poll suggests.

In the poll, respondents ranked technology skills, an ability to work with diverse groups of people, keeping skills current, and having family connections above a four-year college degree.

They certainly didn’t dismiss a college education. More than half said a college degree was very important and 87 percent said it was either very or somewhat important. Those between age 18 and 29 ranked the importance of a degree slightly higher than those 30 and over (55 percent vs. 53 percent). Blacks and Hispanics looked at a degree more favorably than did whites.

The poll was sponsored by National Journal, Allstate and The Atlantic. In interpreting the results, the organizations said the responses about college were “a startling admission in the United States, where college has long been seen as a Holy Grail to the good life.”

Maybe. In context, though, it doesn’t look so startling.

I pieced together data from the Heartland poll and several polls conducted by Gallup for the scholarly organization Phi Delta Kappa. (Most of those are available through the database JStore.) Polls in 1978, 1983, 1985, 2010, 2013, and 2014 asked a question about the importance of college very similar to the one asked in the Heartland poll.

Most certainly, the percentage of Americans saying that a degree is very important has declined substantially since a peak of 75 percent in 2010. If the categories for “very important” and “somewhat” or “fairly” important are combined, though, the decline isn’t nearly so steep.

Those combined totals rose from 82 percent in 1978 to a peak of 96 percent in 2010 before declining to 87 percent in 2015.

It is.

Most people still see a college degree as an important factor in achieving success on the job, yet they have also begun to look at other options, especially as a growing percentage of potential students delay their entrance to college for financial reasons.

Rather than stirring a panic for higher education, though, the polls add one more reason for colleges and universities to clean up their tarnished reputation.

The tech connection

Let’s dig a little deeper into the importance of technology skills.

In April, I wrote about a report from the Educational Testing Service that raised concerns about American millennials’ poor skills when compared with their counterparts around the world.

A report by a group of CEOs (There was a link, but the page no longer exists) offers its own evaluation of that and other data, saying that 58 percent of millennials lack the basic skills they need to solve problems with technology. This is even as millennials use digital media for 35 hours a week, on average, the report said.

The CEO group, which is called Change the Equation, says that this lack of technological know-how will diminish millennials’ job prospects, if it already hasn’t. Most millennials don’t seem to understand how their lack of skills is hurting them, the report said, although only 37 percent of employers say young workers are prepared to stay current with new technologies.

“We must make a point of incorporating technology into how students learn to tackle problems. This does not mean that every young person needs to become a computer scientist, though more certainly should. Instead, students must learn to realize the full potential of technology as a critical aid to human productivity and invention,” the report said.

I don’t dispute the importance of technological savviness. I push my students to use technology for problem-solving, and I emphasize the importance of digital literacy.

Technology isn’t magic, though. Yes, students need technological skills, but that means using hardware and software to solve problems, answer questions, test ideas, communicate solutions, build communities, and stretch our potential.

That all starts with critical thinking, which should be the primary focus of all education. We must incorporate technology into that process. Technology is simply a means to an end, though.

Briefly …

JStor, the online archive, has started a teaching newsletter aimed at helping instructors integrate JStor material into lesson plans. … Alison Phipps, director of gender studies at Sussex University, warns universities against pursuing easy scapegoats in the quest to reduce sexual assault and sexual harassment. In an article for The Guardian, she says “we must avoid enabling institutions to blame particular students or activities for problems they themselves have had a hand in creating.”

More evidence about the weakness of memorization

True learning has little to do with memorization.

Benjamin Bloom explained that with enduring clarity 60-plus years ago. His six-tiered taxonomy places rote recall of facts at the bottom of a hierarchical order, with real learning taking place on higher tiers when students apply, analyze, synthesize, and create.

Deep learning, project-based learning and a host of other high-impact approaches have provided evidence to back up Bloom’s thinking. A study from the Programme for International Student Assessment adds even more evidence. It found that students who memorized mathematics material performed worse than those who approached math as critical thinking, Jo Boaler writes for The Hechinger Report.

Deep learning, project-based learning and a host of other high-impact approaches have provided evidence to back up Bloom’s thinking. A study from the Programme for International Student Assessment adds even more evidence. It found that students who memorized mathematics material performed worse than those who approached math as critical thinking, Jo Boaler writes for The Hechinger Report.

Boaler, a professor at Stanford, says the United States has among the highest percentage of students who approach math as memorization. That’s not surprising, she says, because the teaching of math in the U.S. stresses memorization and speed of calculation for standardized tests. That not only narrows thinking, she says, but creates barriers to students who don’t learn well with memorization. Approaching math as problem solving, modeling, and reasoning expands thinking and expands math’s appeal to students.

“We don’t need students to calculate quickly in math,” Boaler writes. “We need students who can ask good questions, map out pathways, reason about complex solutions, set up models and communicate in different forms.”

That’s good advice for all disciplines.

Need a professor to respond? Try a sticky note. Really.

Need a professor to respond? Try a sticky note. Really.

Experiments by Randy Garner of Sam Houston University found that professors are twice as likely to respond when a request is accompanied by a personal message on a sticky note, Harvard Business Review reports.

Writing for the Review, Kevin Hogan speculates on the reasons this approach works: It’s hard to ignore. It’s personal. And it creates a bit of neon clutter that the brain wants taken care of.

I’ve always considered duct tape a magic solution to most problems. Looks as if I’ll have to expand my toolkit.

Looking at K-12 as the key to raising college graduate rates

Michael J. Petrilli makes a good case that college graduation rates aren’t likely to improve significantly until students come to college better prepared.

Writing for the Thomas B. Forham Institute, he cites statistics showing that the percentage of “college prepared” students (35 percent in 2005) nearly matched the graduation rate of those students eight years later. He says that indicates that most students who are well-prepared for college eventually graduate.

“But until we start making significant progress at the K–12 level — and get many more students to the college-ready level before they land on campus — our dreams for significantly boosting the college completion numbers seem certain to be dashed,” Petrilli writes.

Briefly …

The percentage of students needing remedial math courses at Colorado colleges and universities has declined for three years in a row, Education News reports (There was a link, but the page no longer exist). Among students who started college in 2013, 34.2 percent needed remedial math, down from 40 percent in 2011. (Rates in other states vary widely.) … Eduardo Porter of The New York Times asks whether the federal government shouldn’t get a share of profits from federally financed research ventures in academia. He cites Tesla, Google, GPS, and touch-screen technology as examples of projects that emerged from taxpayer-supported research. … Google has made recordings of its Education on Air event available for viewing. One caveat: All the sessions have separate links but are part of a single video file of more than five hours. That makes skipping among the sessions a challenge.

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Higher education’s tarnished image

Higher education has an image problem. And a trust problem.

That should come as no surprise, given the drubbing that public colleges and universities have taken from state legislatures over the past few years. They have also taken criticism from federal policy makers – along with parents and students – about costs and transparency.

The latest sign of flagging trust comes from a national poll from the Robert Morris University Polling Institute (There was a link, but the page no longer exists) in Pittsburgh.

The latest sign of flagging trust comes from a national poll from the Robert Morris University Polling Institute (There was a link, but the page no longer exists) in Pittsburgh.

More than half of parents polled said colleges and universities weren’t staying current with the demands of the job market or maintaining strong relationships with employers. Jerry Lindsley, president of the Center for Research and Public Policy at Robert Morris, put that into some disturbing context. In a press release from the university, he said:

“Our corporate clients strive to attain overall satisfaction ratings in the high 80s. Even health insurance companies and most utilities receive positive ratings in the high 80s.”

Ouch!

Adding to the sting, the poll found that the number of Americans who rate the value of a bachelor’s degree in positive terms had dropped more than 23 points in the last 10 years, to 44.6 percent.

Not surprisingly, given the rising cost of college, Americans increasingly see a college degree in purely economic terms. An overwhelming 82 percent of those in the Robert Morris poll said job training and preparation at colleges and universities were more important than academic work.

Interestingly, students in the United Kingdom say much the same thing. In a recent poll there, students said that professional experience and training in teaching were more important in instructors than being an active researcher, The Guardian reports. Students who study more, have more contact hours with instructors, and take classes with 50 or fewer students are more satisfied with their education than other students are, the poll said.

Hunter Rawlings, president of the American Association of Universities, points out the danger of a narrow, consumerist view of education. College isn’t a commodity, he argues in an opinion piece for The Washington Post. Rather, it’s an awakening. “It’s a challenging engagement in which both parties have to take an active and risk-taking role if its potential value is to be realized.”

You can’t just buy an education, walk off with it and plug it in. Students’ success depends in large part on the work they are willing to put into that education.

“The ultimate value of college,” Rawlings writes, “is the discovery that you can use your mind to make your own arguments and even your own contributions to knowledge.”

He’s right. I’ve made that case myself. And yet those of us in higher education face an enormous challenge in making that case to students, parents and legislators who increasingly see education as a means to a very specific end, not as a process of mental development.

We have our work cut out for us.

Sage advice about non-traditional students

Jeff Fanter, vice president for enrollment, communications and marketing management at Ivy Tech Community College in Indiana, offered this excellent insight during an interview with The Evolllution:

“I firmly believe many non-traditional students come into the door of higher education with one foot outside the door at all times. If you give them a reason to take their other foot back outside the door and walk away they will.”

Briefly …

Researchers at the University of California, Irvine, will explore the influence digital text formatting has on reading abilities in middle school students, The Journal reports. … Writing in The Christian Science Monitor, Robert Reich argues that the United States needs to reinvent its entire education system. … Minnesota’s public colleges and universities will receive their full appropriation from the state legislature only if they meet several guidelines, including increasing graduation rates and job placement, Minnesota Public Radio reports.

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Teaching is important, but not at the expense of everything else

Kerry Ann Rockquemore offers excellent advice about what she calls “the teaching trap.” (There was a link, but the page no longer exists).

By that, she means putting so much of yourself into your teaching that you have no time or energy for research, writing or life outside the office. She writes:

“If you find yourself coming to campus early and staying late, if you’re spending every weekend grading and preparing for the next week’s classes, if you’re answering student’s text messages into the wee hours of the night, if you’re sacrificing sleep and/or pulling all-nighters in order to get ready for the next day’s class meeting, and – as a result – you haven’t spent any time moving your research agenda forward or investing in your long-term success, then you may have fallen into the teaching trap.”

“If you find yourself coming to campus early and staying late, if you’re spending every weekend grading and preparing for the next week’s classes, if you’re answering student’s text messages into the wee hours of the night, if you’re sacrificing sleep and/or pulling all-nighters in order to get ready for the next day’s class meeting, and – as a result – you haven’t spent any time moving your research agenda forward or investing in your long-term success, then you may have fallen into the teaching trap.”

She provides several reasons this can happen but also offers ways of balancing academic life. Those include setting aside writing time every day, consulting with colleagues about how they handle their workloads, avoiding Ratemyprofessor.com (a perfectionist tendency), and seeking advice from your school’s teaching center.

I’ll add my own plug for her last suggestion. CTE offers many programs, workshops, discussions and publications to help faculty members improve their teaching (which includes finding a healthy balance). We also visit classes and consult with individual faculty members and departments about specific problems.

Teaching can sometimes feel like an all-encompassing, individual profession. It doesn’t have to be. In fact, all teachers are part of a broader community. Recognizing that and then joining the community helps make us all better.

Region makes a difference for recent grads

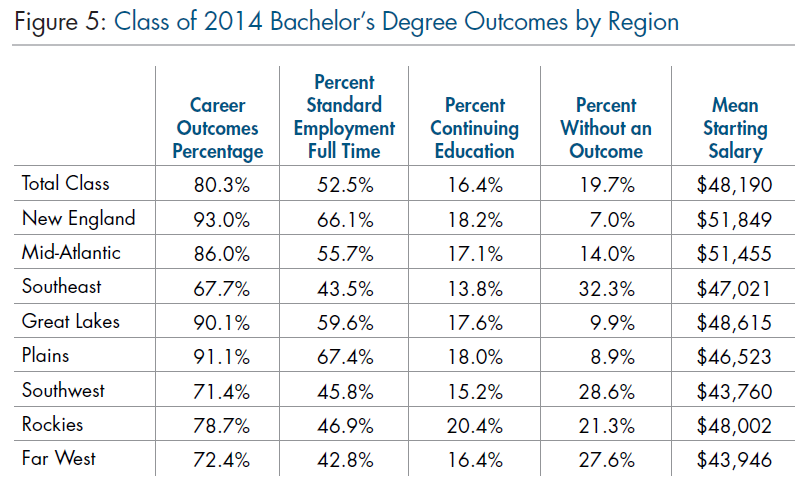

More than 65 percent of 2004 graduates from the Plains states and New England found full-time jobs within six months of leaving college, a new survey says.

Those percentages (Plains, 67.4 percent; New England, 66.1 percent) were the highest among all regions. Overall, 52.5 percent of 2004 graduates reported finding full-time jobs within six months of graduating.

More than 90 percent of students from colleges in those areas, along with those in the Great Lakes states, reported a positive “career outcome,” meaning they had found a job or were continuing their education six months after graduating, the survey said. That is far higher than other regions of the United States. Colleges from the Southeast reported the lowest percentage (67); the national average was 80 percent.

The survey found little difference among institutions in urban, suburban or rural areas. (It also broke down job status based on area of study, but that is too detailed to go into here.)

Graduates from private, nonprofit colleges and universities (58.5 percent) were far more likely to have found jobs than their counterparts in public institutions (48 percent), the survey said, and those with professional degrees were slightly more likely than those with liberal arts degrees to have found full-time jobs (58.7 percent vs. 53.8 percent). The survey’s authors say this is partly the result of student expectations: Those with professional degrees tend to focus on getting jobs; those with liberal arts degrees often go to graduate school.

What are we to make of the data? The report doesn’t really say, except to point out that more than 20 percent of graduates were “adrift” six months after they left college. I found the regional data especially interesting. I have ideas about that, but I won’t speculate without seeing further data.

The survey, from the National Association of Colleges and Employers (There was a link, but the page no longer exists), contains data from more than 200 colleges and universities. Its creators say it is the first such survey to use a common methodology among all participants, and they told Inside Higher Ed that they hope it will create a baseline for future surveys of graduates.

Briefly …

In an article for Faculty Focus, Berlin Fang warns against becoming a “helicopter professor,” saying it is important to let students struggle with concepts and find answers on their own. … Heather Cox Richardson, a professor at Boston College, writes for Slate on what she calls Gov. Scott Walker’s new Wisconsin Experiment, putting it into the context of “eighty years of maligning universities as hotbeds of socialism in an attempt to undercut workers’ influence in government.” … Jill Barshay of the Hechinger Report says that student debt falls most heavily on three types of students: graduate students, students at for-profit colleges, and dropouts.

Doug Ward is an associate professor of journalism and the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Dueling opinions on higher education funding

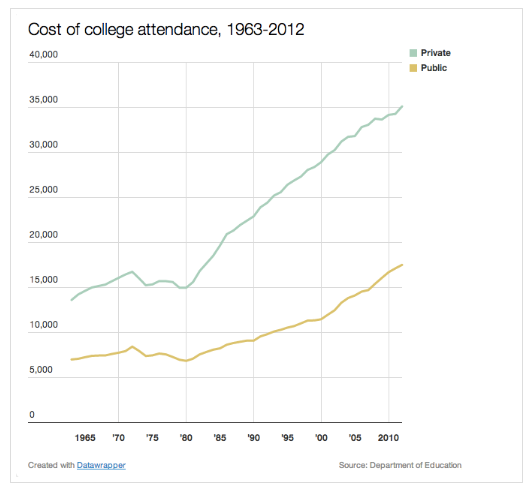

No one disputes that college tuition has risen substantially over the past 20 years.

Ask why, though, and you’ll get vastly different answers.

Writing in The New York Times, Paul Campos, a professor at the University of Colorado, dismisses the idea that declining state subsidies have led to rising tuition. Instead, he writes, “the astonishing rise in college tuition correlates closely with a huge increase in public subsidies for higher education.”

That partly depends on when you start measuring.

Adjusted for inflation, funding for higher education is 10 times higher than it was in the 1960s, Campos says. Some of that increase has been driven by a larger percentage of Americans going to college, he says, although tuition has risen even faster than legislative financing. He attributes much of the rise to the “constant expansion of university administration.”

Campos says an argument can be made for the increases in spending and the growth in administration, except for the skyrocketing salaries of top administrators. Ultimately, though, he argues, tuition increases aren’t tied to state cuts.

Tom Lindsay of Forbes cheers Campos’s argument, adding his own figures to back up those Campos provides. Lindsay says his own research about Texas shows “that a mild decrease in state funding … has been accompanied by a wild increase in university tuitions and fees.”

On the other side of the spending argument is the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, which focuses on how government policies affect low-income Americans. Its latest report shows that state spending on higher education has dropped more than 20 percent since 2007-08, with some states cutting more than 35 percent. Tuition has increased 29 percent during that time.

Some states have increased funding to higher education by an average of 3.9 percent over the past year, the center said, but 13 states have continued to cut.

So who’s right? All of the above, at least to an extent.

There’s no dispute that financing for public colleges and universities has risen considerably since the 1960s. Nor is there any dispute that education at all levels has taken substantial cuts in state financing since the 2008 recession.

Have tuition increases since 2008 been tied, at least in part, to declining state support? Of course they have. Do those state cuts fully explain the tuition increases? Definitely not. What about the longer term? That’s where Campos and Lindsay have a strong argument. Tuition rates grew enormously even as public spending on higher education rose from the 1960s to 2008.

Whatever your take on rising tuition and state cuts, those issues need to be framed in terms of bigger questions:

- What type of public higher education system do we want?

- How much are states and potential students willing to pay for the education those institutions deliver?

- And how can we keep public education from becoming an elite-only opportunity? That is, how do we keep it truly public?

Those are the harder questions we have yet to answer satisfactorily.

That other big college expense

Discussions about rising tuition rates often overlook an even bigger expense for many families: room and board.

According to NPR, those costs are rising even faster than tuition rates.

It cites statistics from the College Board, saying that the cost of room and board at public universities has risen by more than 20 percent since 2009.

Among the drivers of cost, according to NPR: aging dorms that need to be replaced; student demand for gourmet menus and luxury rooms, along with universities trying to keep pace with one another in this area; use of higher-priced local food; and extended hours for dining halls.

It also points to another cause: As colleges and universities have been pressed to keep tuition increases down, some have pushed up the cost of student housing to help fill budget gaps.

Briefly …

U.S. college enrollment fell by about 200,000 between 2012-13 and 2013-14, The Hechinger Report says, and the proportion of students who moved immediately from high school to college dropped four percentage points between 2009 and 2013. More students are also enrolling part time, Hechinger says, and a slightly higher percentage of students are staying after their freshman year. … Penn State researchers will use Apple watches to interact with students in class, send notifications outside of class, and promote reflection on learning, The Chronicle of Higher Education reports.

Doug Ward is an associate professor of journalism and the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.