Kerry Ann Rockquemore offers excellent advice about what she calls “the teaching trap.” (There was a link, but the page no longer exists).

By that, she means putting so much of yourself into your teaching that you have no time or energy for research, writing or life outside the office. She writes:

“If you find yourself coming to campus early and staying late, if you’re spending every weekend grading and preparing for the next week’s classes, if you’re answering student’s text messages into the wee hours of the night, if you’re sacrificing sleep and/or pulling all-nighters in order to get ready for the next day’s class meeting, and – as a result – you haven’t spent any time moving your research agenda forward or investing in your long-term success, then you may have fallen into the teaching trap.”

“If you find yourself coming to campus early and staying late, if you’re spending every weekend grading and preparing for the next week’s classes, if you’re answering student’s text messages into the wee hours of the night, if you’re sacrificing sleep and/or pulling all-nighters in order to get ready for the next day’s class meeting, and – as a result – you haven’t spent any time moving your research agenda forward or investing in your long-term success, then you may have fallen into the teaching trap.”

She provides several reasons this can happen but also offers ways of balancing academic life. Those include setting aside writing time every day, consulting with colleagues about how they handle their workloads, avoiding Ratemyprofessor.com (a perfectionist tendency), and seeking advice from your school’s teaching center.

I’ll add my own plug for her last suggestion. CTE offers many programs, workshops, discussions and publications to help faculty members improve their teaching (which includes finding a healthy balance). We also visit classes and consult with individual faculty members and departments about specific problems.

Teaching can sometimes feel like an all-encompassing, individual profession. It doesn’t have to be. In fact, all teachers are part of a broader community. Recognizing that and then joining the community helps make us all better.

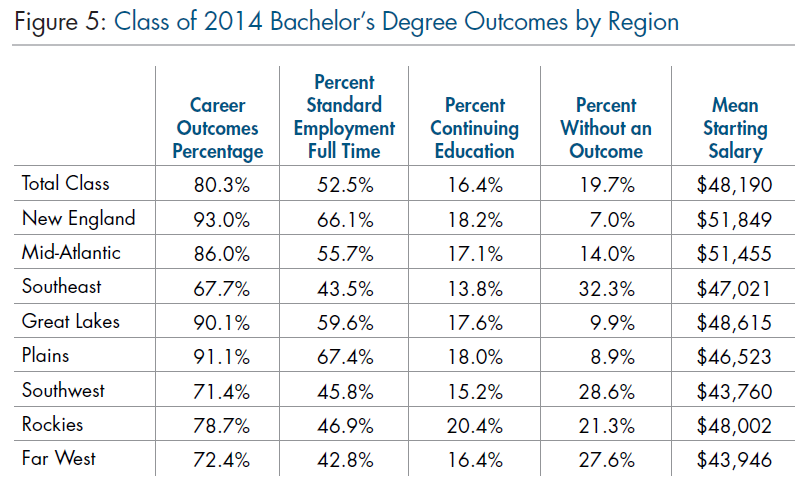

Region makes a difference for recent grads

More than 65 percent of 2004 graduates from the Plains states and New England found full-time jobs within six months of leaving college, a new survey says.

Those percentages (Plains, 67.4 percent; New England, 66.1 percent) were the highest among all regions. Overall, 52.5 percent of 2004 graduates reported finding full-time jobs within six months of graduating.

More than 90 percent of students from colleges in those areas, along with those in the Great Lakes states, reported a positive “career outcome,” meaning they had found a job or were continuing their education six months after graduating, the survey said. That is far higher than other regions of the United States. Colleges from the Southeast reported the lowest percentage (67); the national average was 80 percent.

The survey found little difference among institutions in urban, suburban or rural areas. (It also broke down job status based on area of study, but that is too detailed to go into here.)

Graduates from private, nonprofit colleges and universities (58.5 percent) were far more likely to have found jobs than their counterparts in public institutions (48 percent), the survey said, and those with professional degrees were slightly more likely than those with liberal arts degrees to have found full-time jobs (58.7 percent vs. 53.8 percent). The survey’s authors say this is partly the result of student expectations: Those with professional degrees tend to focus on getting jobs; those with liberal arts degrees often go to graduate school.

What are we to make of the data? The report doesn’t really say, except to point out that more than 20 percent of graduates were “adrift” six months after they left college. I found the regional data especially interesting. I have ideas about that, but I won’t speculate without seeing further data.

The survey, from the National Association of Colleges and Employers (There was a link, but the page no longer exists), contains data from more than 200 colleges and universities. Its creators say it is the first such survey to use a common methodology among all participants, and they told Inside Higher Ed that they hope it will create a baseline for future surveys of graduates.

Briefly …

In an article for Faculty Focus, Berlin Fang warns against becoming a “helicopter professor,” saying it is important to let students struggle with concepts and find answers on their own. … Heather Cox Richardson, a professor at Boston College, writes for Slate on what she calls Gov. Scott Walker’s new Wisconsin Experiment, putting it into the context of “eighty years of maligning universities as hotbeds of socialism in an attempt to undercut workers’ influence in government.” … Jill Barshay of the Hechinger Report says that student debt falls most heavily on three types of students: graduate students, students at for-profit colleges, and dropouts.

Doug Ward is an associate professor of journalism and the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Tagged collaborative learning, Education Matters, reflective teaching, student surveys