Introducing Ethics to Geography Graduate Students Using Various Instructional Materials

An accessible version of the documents on this site will be made available upon request. Contact cte@ku.edu to request the document be made available in an accessible format.

To help students understand the range of ethical issues that academic and non-academic geographers may encounter in their jobs, a geography professor expands his instruction in ethics education.

- Terry A. Slocum (2009)

GEOG 806, Basic Seminar, is a two-hour class for master’s students. It is the second of two introductory courses, and it is designed to provide experience in the development of research proposals, as well as exposure to methodologies in geography. The course includes individual examination of special topics that require preparation, presentation, and critical evaluation of research proposals. In Spring 2009, I revised the course by expanding an ethics component. My goal was for students to be able to determine when ethical issues are likely to be a concern and, most importantly, determine what sort of ethical action is appropriate in different situations.

Using various instructional materials (lecture/class discussions, case studies, readings, and a brief bibliography on ethics), I introduced the topic of ethics. I focused on key steps involved in ethical decision-making as students and I worked through a case study. Students then formed small groups and worked through three additional case studies. Each student was asked to provide a written analysis of his or her case study, and the two- to four-page papers were evaluated with a grading rubric.

Student work on the ethics assignment was quite good. Seven students earned an A for their papers, one earned a B, and two earned a C. In addition, students appeared to enjoy learning about ethical issues, and they found the small group discussions of case studies useful.

In general, I was very happy with the work that students completed. Most students paid careful attention to the eight steps presented in one of the readings, and those students who paid careful attention received the highest grades. Although students’ thesis proposals did not reflect increased sensitivity to ethical issues, many of the proposals did not consider problems where ethical issues would be of paramount importance.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No 0629443. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

GEOG 806 (pdf) is the second of two required introductory courses for geography master's students. It deals with approaches to geographic problems and involves individual examination of special topics that require preparation, presentation, and critical evaluation of research proposals. A major purpose of the course is to develop master's thesis proposals, but the course also considers the development of other kinds of proposals (e.g., for grant funding) and issues related to professional development (e.g., preparation of the curriculum vitae). In the syllabus for Spring 2008 (.docx), you will note that an ethics component has been part of the class, but the primary purpose of that component was for the students to get proper permission for using human subjects in research from the Human Subject Committee of Lawrence.

Goals for ethics instruction in GEOG 806

My intention was to enable students to appreciate more fully the range of ethical issues that academic and non-academic geographers are likely to encounter in their jobs. Students should be able to determine when ethical issues are likely to be a concern and, most importantly, determine what sort of ethical action is appropriate in a particular situation.

I introduced the topic of ethics in a 40- to 50-minute lecture/discussion during class. First, I covered the three basic approaches to ethical decision-making: consequentialist, deontological, and integrity. Then I focused on key steps involved in ethical decision-making, using the steps provided in Chapter 4 of Treviño and Nelson’s Managing Business Ethics: Straight Talk about How to Do it Right (2004).* I introduced these steps through a lecture/discussion focusing on case 1 shown below. Students were provided the brief bibliography on ethics (.docx), and asked to read the chapter on ethics in our main course text [Chapter 2 of Locke et al. (2007)**], and pp. 88-100 in Chapter 4 of Treviño and Nelson (2004).

Case study 1: authorship

In addition to introducing case study 1 in lecture, I had students work through case studies two, three, and four (see links at right) during class in small groups of three to four students, during which I purposefully left the room.

A graduate student writes a master's thesis and her advisor indicates that the thesis is of publishable quality. The advisor provides guidance on the thesis, but the student did the bulk of the research and writing. The advisor encourages the student to write an article based on the thesis, but the student does not wish to take the time to write the article, although she is willing to edit the article, if the advisor writes it. The advisor indicates that he is willing to write the article, presuming that the student's name is included as a co-author. After some discussion, the faculty member and student agree that the faculty member's name will appear first on the article. Is this appropriate?

Evidence of student understanding

In addition to discussing the case studies in class, each student was asked to provide a written analysis of his or her case study. I asked students to write a two- to four-page double-spaced paper that analyzed the case study using the specified grading rubric (.docx). This rubric borrows heavily from Elizabeth Friis’ work, but also includes issues pertaining to writing quality.

In grading students’ responses, I utilized the grading rubric, but I would describe that as a subjective process as I did not attempt to assign a grade to each section of the grading rubric.

I also examined the nature of the ethical issues that students provided in their thesis proposals, in order to compare the extent to which students considered ethical issues with a prior semester in which I did not place as much emphasis on ethical issues.

*Treviño, L. K. and Nelson, K. A. Managing Business Ethics: Straight Talk about How to Do it Right. (2004). Third Edition. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Chapter 4 was very useful for my course.]

** Locke, L. F., Spirduso, W. W. and Silverman, S. J. (2007) Proposals that Work: A Guide for Planning Dissertations and Grant Proposals. Fifth Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [This is the book for my course; chapter 2 deals with ethics.]

Case 2: map symbolism

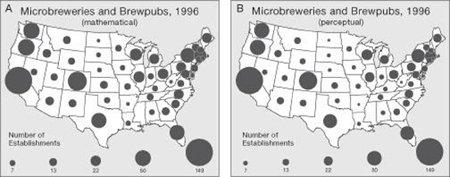

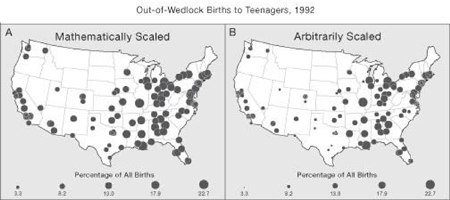

When constructing a proportional circle map, two basic scaling methods are possible: mathematical and perceptual. In mathematical scaling, circles are sized in direct proportion to the data (i.e., a data value twice as large has a circle twice as large), whereas in perceptual scaling circles are sized to account for perceived underestimation of larger circles (see Figure 1). The net result of perceptual scaling is that there is a greater difference between the smaller and larger circles, but the overall pattern is similar to mathematical scaling. Perceptual scaling can be modified, however, so that rather than simply accounting for perceived underestimation of larger circles, the differences between the smaller and larger circles are exaggerated: this is known as arbitrary scaling (see Figure 2).

A researcher writing an article for the The New York Times wishes to stress the differences in the percentage of out-of-wedlock births in various U.S. metropolitan areas. Thus, she utilizes the arbitrary scaling approach shown in the right-hand map shown in Figure 2. Is arbitrary scaling ethically appropriate?

Figure 1. A Comparison of mathematically and perceptually scaled circle.

Figure 2. A Comparison of mathematically and arbitrarily scaled circle.

Case 3: Negotiating the social relations of research in an international context

(Courtesy of Professor Chris Brown, University of Kansas)

A researcher goes to a Third World country to study whether development project funds from the World Bank to groups of disadvantaged groups of small farmers, rubber tappers, and indigenous peoples have led to changes in the political scene at the county level in the state of Rondonia, Brazil in the Amazon. A surrogate measure for “changes in politics,” the dependent variable, is changes in voting patterns (percent votes for leftist candidates at various levels of governmet), and these data are available on the web.

Details of the project development funds (amount of money, the particular community groups in the county that are funded, etc.), the independent variable, are “public documents,” and should be available for people to see. The state government group that holds the documents, however, can block access to them by foot-dragging, demanding bribes, etc. The researcher has to work through personal contacts over a period of time to get access to these documents, but the researcher also knows that if those contacts knew that the research involved the study of the impact of these projects on politics (the dependent variable), that the access may be denied, due to the desire of the state government agency holding the documents to appear politically neutral. Is it ethical or unethical for the researcher to withhold information on the research project's dependent variable from the state government officials holding the information on the independent variable?

Case 4: Caribou migration routes

(After an example provided in “Ethics Education for Future Geospatial Technology Professionals” (pdf), or, click this alternative link.)

An environmental consulting firm in Alaska is hired by a natural gas utility to produce a map of a proposed pipeline through a portion of northeast Alaska in preparation for a public hearing (a hearing attended also by potential funders for the project). The company already has a pipeline route in mind but wants to assess this further within the context of the physical landscape, private land ownership, and public lands data. In the end they want to choose the shortest, most direct route to minimize capital expenditures for construction and pipeline efficiency.

A GIS analyst within the consulting firm is assigned to this project and proceeds to gather all pertinent data including existing topographic maps (DEMs), potential landslides, land use, land cover, geologic fault, soils, roads, railways, streams, station points, resident locations, administrative boundaries (including land ownership), vegetation, regulatory data, and subsurface seismic data. The project will use these data to analyze a variety of variables, such as slope of terrain; number of stream, road, and railroad crossings; existing laws and regulations (e.g., proximity to wetlands, costs associated with right-of-way, etc.); and proximity to population centers. The analyst plans to use these variables to define an optimum pipeline route.

The analyst also has access to caribou migration routes throughout the region from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Although the proposed path of the pipeline itself will not fall within wildlife refuges, the migration corridors for this important species move beyond the reach of refuges. In fact the analyst found that these migration routes intersect the proposed pipeline at several points. The analyst brings this finding to the attention of her supervisor. For reasons unknown to the analyst, the supervisor instructs her to remove the caribou migration routes from any maps prepared for the public hearing. What should the analyst do?

Overall, I felt that the exercise worked reasonably well. Students appeared to enjoy learning about ethical issues, and they found the small group discussions of case studies useful. Unfortunately, it is not possible to specify exactly what the level of ethical understanding was during the group discussions, since I purposely left the room during this period. One limitation is that 90 minutes may not have been enough time for my initial lecture and the small group discussions. Two hours would probably be a more reasonable amount of time.

Four examples of high level work are shown below:

Four examples of intermediate level work are shown below:

Two examples of lower level work are shown below:

- Student 9 (pdf)

- Student 10 (pdf)

Class distribution

A+2

A2

A-3

B+1

C+1

C1

A-level: 7

B-level: 1

C-level: 2

In general, I was very happy with the work that students completed. Most of the students paid careful attention to the eight steps presented in the Treviño and Nelson book, which is not surprising since I focused on these in the grading rubric. Still, I noted that a couple of students did not pay careful enough attention to the eight steps and the grading rubric.

Generally, those students who paid careful attention to the eight steps received the highest grades. One exception was a student who attempted to use the eight steps, but misinterpreted the steps and used poor grammar. On reflection, I probably need to emphasize that students’ answers should specifically respond to each of the points listed in the grading rubric.

Although my gut reaction is that students became more sensitive to ethical issues as a result of completing the exercise, their thesis proposals did not necessarily reflect this. In fact, compared to the preceding semester, the proposals were not more likely to consider ethical issues. One must keep in mind, however, that many of the proposals did not consider problems where ethical issues would be of paramount importance.

The ethical issues covered in the exercise could be incorporated into a broad range of geography courses. One issue that I struggled with (and I'm sure others will, too) is how to fit this topic into an already-full syllabus. Possibly, I need to expand this two-hour class into a three-hour class.