By Doug Ward

Research about learning and artificial intelligence mostly reinforces what instructors had suspected: Generative AI can extend students’ abilities, but it can’t replace the hard work of learning. Students who use generative AI to avoid early course material eventually struggle with deeper learning and more complex tasks.

On the other hand, AI can improve learning among motivated students, it can assist creativity, and it can help students accomplish tasks they might never have tried on their own.

Keep in mind that nearly all the research over the past three years focuses on AI integrated into current class structures and learning environments. We need that kind of research to help us in the short term. AI systems are becoming more capable, autonomous, and ubiquitous, though, and we must reimagine what and how we teach and how we assess learning. Until we do that, we will be forced to take repeated stop-gap measures that will be as frustrating as they are futile.

My advice: Keep an open yet critical mind as we learn how and where generative AI best fits into teaching and learning. Experiment with AI tools and consider how they might assist student learning and extend the abilities of those working in your field. Share what you are learning with colleagues. And remind students of the perils of substituting AI for thinking.

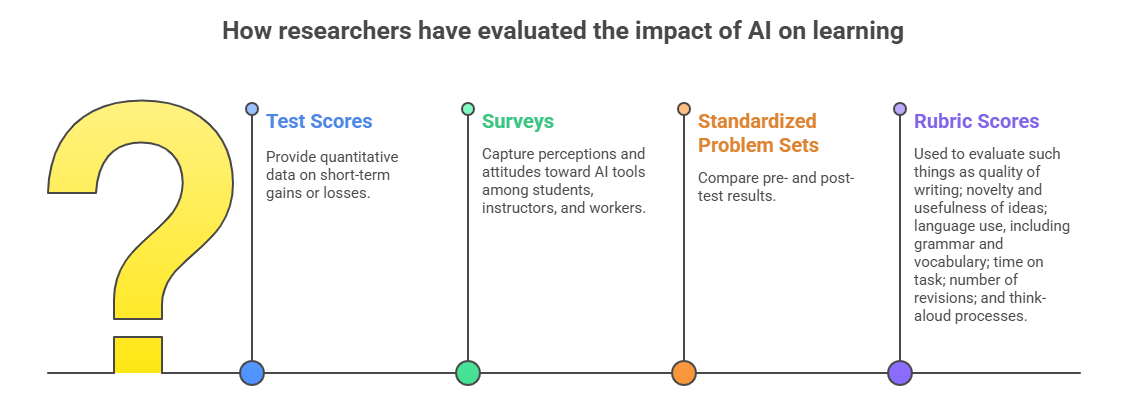

What follows is a breakdown of major themes in research into AI in education and workplaces. It reflects ideas from hundreds of studies across many disciplines. Findings are often contradictory or unclear, and varying definitions and approaches often make comparison difficult. Confounding that, a recent paper challenges the validity of much recent research into generative AI, saying that it is rushed and fails to separate the tool (generative AI) from pedagogical changes made when students use the tool.

Thinking, learning, and use of AI

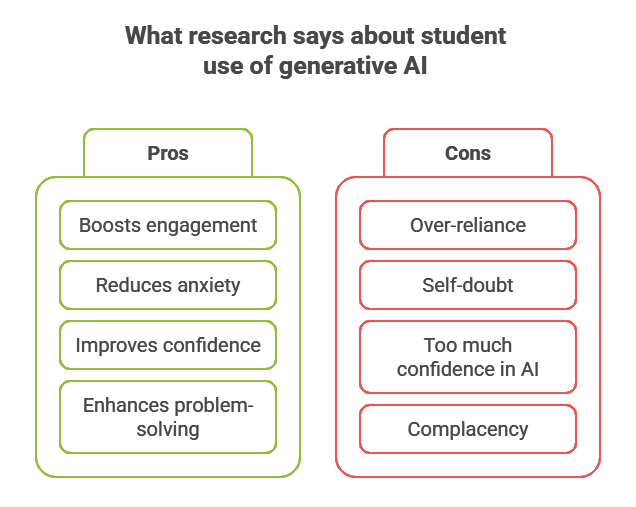

Research into use of generative AI in education provides no single, clear recommendation. Some studies suggest that while AI tools can improve efficiency and accessibility, its overuse can diminish skills and critical thinking in the long run and potentially diminish empathy and creativity. Students who hand off foundational work to generative AI struggle when they try to complete later tasks, including coding, on their own. Psychologists call this avoidance of thinking “cognitive offloading” or “metacognitive laziness.” In one study, younger users of generative AI were prone to over-rely on AI tools for critical thinking.

Another study found lower brain connectivity among study participants who used generative AI for a writing project compared with those who used Google search or no assistance in writing. The lead author urged caution in interpreting the findings, though. Increased brain connectivity isn’t necessarily better, she said, and brain connectivity was higher among participants who used generative AI in later writing tasks. Two authors on that study were also part of another project in which an adaptive chatbot increased brain activity but not learning. A workplace study found a positive correlation between critical thinking and workers completing tasks on their own. Researchers also found that workers were more likely to engage in critical thinking when they were confident in completing tasks on their own. Thinking diminished when they relied too much on AI tools, a finding that is common among current literature.

One meta-analysis found that a vast majority of studies reported positive effects of generative AI on learning, motivation, and higher-order thinking. Most of those were in university-level classes in arts and humanities, health and medicine, or social sciences. Language education has gained considerable attention from researchers. Studies in that area suggest that the gains are the result of generative AI’s ability to provide personalized content, immediate access to information, diverse perspectives, and deeper perspectives on course material. Some researchers question the validity of some current research, though, saying it fails to account for whether use of generative AI improves student learning or whether high-performing students are more likely to use generative AI. Similarly, they question whether studies that suggest use of generative AI diminishes thinking have differentiated between AI tools and the skills of the students using the tool. One meta-analysis refers to this as a “directionality problem.” Studies of higher-order thinking often rely on students’ perceptions, the analysis says. The studies also focus on short-term gains (one to four weeks).

Another meta-analysis suggests that generative AI is most effective when used in problem-based learning, in courses where skills and competencies are well-defined, and in courses of four to eight weeks. It says, though, that integration of generative AI tools can improve higher-order thinking in nearly any course, largely because they provide constant feedback, guidance, and assessment, allowing students to reflect on their learning continually. One study also suggests that generative AI can improve higher-order thinking, especially in STEM courses. Researchers speculate that ChatGPT’s ability to explain complex topics in accessible language plays a role in that, allowing students to engage in a wider range of critical-thinking activities. Similarly, another study found that use of chatbots resulted in substantially improved understanding of medical terminology, and yet another study suggests that introduction of an AI tutor can help students develop skills for effective work in teams. A study of design students found that use of generative AI led to deeper analysis of sketches, broadened students’ scope of thinking about projects, supported complex problem-solving, and improved metacognition. Researchers said generative AI was a valuable collaborator in higher-order thinking. Another study found that engagement with chatbots could help reduce belief in conspiracy theories, even among people who whose beliefs were deeply held.

Other research suggests that students benefit most from generative AI when they already understand core concepts and have a clear sense of what they are trying to accomplish. One study argues that students’ use of generative AI tools for low-level tasks can skew their perceptions of the tools’ weaknesses and that helping them better understand those weaknesses can lead to better decisions. In terms of Bloom’s taxonomy, generative AI automates lower levels of the taxonomy by retrieving, organizing, and explaining information. Other researchers warn that repeated use of generative AI for higher-order tasks can create a dependency that diminishes students’ engagement in critical thinking. The title of a study summaries that line of research well: “ChatGPT is a Remarkable Tool – For Experts.” Even experts worry about overuse of generative AI, though. One programmer wrote about noticing his skills wane as he relied on Copilot. And in a recent hackathon pitting AI-assisted programming teams against teams working unaided, participants worried about being placed on non-AI teams. A team using generative AI won.

AI and student confidence

Some studies suggest that AI class assistants can improve student engagement and confidence, especially in handling complex problems. A survey by the Society of Industrial and Applied Mathematics suggests that use of AI can reduce students’ anxiety about math by providing personalized assistance and feedback. The survey also suggests that AI can improve student confidence in large classes. Others, though, say that use of generative AI can lead some students to question their academic abilities and feel reliant on AI for completing their coursework. Some of that may be related to a mismatch between self-confidence and individuals’ ability to evaluate the output of AI systems, one study suggests. Students need a better understanding of AI systems and their reliability, it and other studies argue. That understanding falls under an emerging approach called AI literacy, which can improve student confidence and innovative problem-solving skills.

The combination of student confidence and AI has other complexities. In one study, students were overly trusting of results from ChatGPT and less reflective than students who used electronic search to gather information. Microsoft researchers found that workers who had greater confidence in generative AI generally made less of an effort to evaluate, revise, analyze, or synthesize AI-generated content. Workers were less likely to evaluate chatbots critically when they were pressed for time or lacked the skills to improve the quality of AI output. Other studies suggest the same behavior. The Nielsen Norman Group calls this Magic 8 Ball Thinking, a reference to a toy that provides random answers when you turn it over. This type of thinking causes problems when people overestimate the capabilities of generative AI and become complacent in its use, especially if they use it in research outside their area of expertise and assume a response is accurate.

Chatbots and student success

A study involving physics students found that those who used a chatbot tutor at home scored considerably better on exams than students who were exposed to the same material in an interactive lecture. Those students also spent less time preparing for an exam and were more likely than their peers to take on challenging problems. Similarly, researchers have found that AI tools can be especially beneficial in self-directed learning, improving knowledge and skill development. Another study, though, found that student use of generative for studying resulted in lower grades. A meta-analysis suggests that generative AI can improve active participation in class activities, encourage experimentation and innovation, and improve emotional engagement if students feel less inhibited in asking assistance from a chatbot than they would their instructors. At Kennesaw State, a composition instructor found that student use of a chatbot connected to an open textbook improved the pass rate in composition classes and has helped “empower students to take ownership of their learning.”

Generative AI can be particularly helpful for students who are non-native English speakers or who have communication disabilities by providing tailored support and scaffolding. It helps translate text and explain complex ideas. It also allows students with weak language skills to improve their written work substantially. That includes large numbers of international students and students whose families don’t speak English at home. The improvements were greatest, though, among students with college-educated parents who had higher incomes. The researchers said the results suggested that those students had learned to use the technology well, not that they had improved their core skills. An analysis of discussion-board posts suggests that generative AI allowed students with weak language skills to improve their written work substantially, according to The Hechinger Report. That includes large numbers of international students and students whose families don’t speak English at home. The improvements were greatest among students with college-educated parents who had higher incomes. As Hechinger says, though, the results suggest that those students have learned to use the technology well, not that they have improved their core skills.

AI and creativity

Research on creativity and AI shows widely varying results, much like research into other aspects of generative AI. In some cases, generative AI can improve creativity in writing, a study in Science Advances suggests, and the work of writers who drew more ideas from AI was considered more creative than that of writers who used it for one idea or not at all. The downside, the researchers said, was that the stories in which writers used generative AI for ideas had a sameness to them, while those created solely by humans had a wider range of ideas. An MIT study similarly found that essays in which participants used generative AI were much more similar than those created by people who did not use AI.

Another study found that generative AI could decrease creativity in some circumstances. Novice designers who sketched by hand or drew inspiration from image searches created a wider variety of designs than those who used generative AI, and their work was judged more original. Yet another study is unambiguous, saying that students’ use of ChatGPT is detrimental to their creative abilities. A study involving design students, though, found that feedback from generative AI tools led to small improvements in students’ work.

In a comparison of humans and generative AI, a study from the Wharton School found that humans working alone produced a broader range of ideas for a new consumer product than ChatGPT did. The researchers said they identified prompting strategies to improve the diversity of ideas ChatGPT produced, though. Another study concluded that ideas from humans were more original and sophisticated than those produced by ChatGPT. The authors said, though, that generative AI could improve human creativity and innovation, in part by bringing in concepts from outside fields.

AI and feedback to students

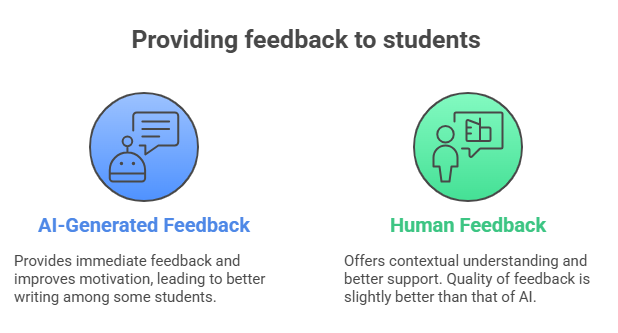

The ability of generative AI to provide helpful feedback to students is one area where researchers generally agree – even as they urge caution. One recent study is among many suggesting that AI-generated feedback can help students improve their writing. One author of that study suggested, though, that the effect of AI-generated feedback might diminish as its novelty declines. A meta-analysis found that repeated rounds of AI-generated feedback led to improved student writing, mostly backing results of an earlier meta-analysis. Most of those studies compared the writing of students who received automated feedback with that of students who received no feedback. Two researchers of first-year writing courses, though, found that ChatGPT-produced feedback adhered to overly narrow criteria and often ignored prompts intended to guide it in working with more complex genre requirements.

Another study found that teachers provided better feedback on student writing than ChatGPT did, although the researchers said the differences were so small that they were nearly insignificant. Human evaluators understood the context of the student work and provided better feedback when students needed to include more supporting evidence, they said. It and other studies said, though, that the immediate feedback generative AI provided improved student motivation and engagement. Researchers say that educators should not assume that automated feedback will work for every student. It works best, they said, when combined with instructor feedback and other individual instruction.

In a study of videos and learning, researchers found that participants preferred human-created videos to AI-generated videos by a small margin. The study found no difference, though, in learning from either type of video, with researchers predicting that use of AI-generated video in education would proliferate as the technology improves. The study supported earlier research that an AI-generated avatar and the AI-generated voice of an instructor improved both motivation and learning among students.

What should we make of this?

The current research into generative AI in education provides insights but no clear direction, and things continue to change rapidly. We are learning a few things, though:

AI isn’t a replacement for learning. That may seem obvious, but students need to hear it frequently. Students have used generative AI to exploit the many weaknesses in our educational system: an emphasis on grades, a reliance on large classes, and a use of a handful of assessments as a means of determining success or failure, just to name a few. We need to build trust among students and we need to do a better job of helping them understand that learning takes time and effort and that occasional failure is an inevitable part of the process. For that to work, though, we must ensure that short-term failure can be turned into long-term success.

AI literacy is crucial. By this, I mean understanding how generative AI works, how it can be used effectively and ethically, why it is fraught with ethical issues, and how it is affecting jobs and society. Most students understand the downsides of substituting generative AI for their own thinking, and they want to learn more about it in their classes. They also have ideas for how instructors and institutions should handle generative AI (see the accompanying chart from Inside Higher Ed). We must provide opportunities to learn about generative AI in our courses, and discussions about its use should become a routine part of teaching.

We must find ways to use AI effectively. AI-provided feedback shows promise, and we need to keep experimenting with it and other approaches of integrating AI into teaching and learning. For example, how can it help students understand difficult concepts? How can instructors use it to adapt to students’ individual needs? How might it help instructors reenvision assignments? How can we create tools that help guide students when instructors aren’t available and that supplement learning? Those are just a few questions that many instructors and institutions are exploring.

There is no single ‘solution.’ I put “solution” in quotation marks because many faculty members seem to be looking for a policy, an approach, a method, an assessment design, a detector or something else that will “save” education from generative AI. There is no such thing. Rather, this is what some authors have described as a “wicked problem,” one with no single definition and no overarching solution. We must continue to experiment, weigh tradeoffs, and recognize that the changing nature of AI tools will force us to constantly adapt and iterate. Reflective teaching has become more important than ever.

Doug Ward is associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications.

Tagged artificial intelligence, future of higher education, research, student engagement