Among academics, online education inspires about as much enthusiasm as a raft sale on a cruise ship.

That’s unfortunate, given that higher education’s cruise ship has a hull full of leaks and has been taking on water for years.

The latest evidence of academic disdain for online education comes from the Online Report Card, which is sponsored by the Online Learning Consortium and other organizations (There was a link, but the page does not exist anymore), and has been published yearly since 2003. It is based on surveys conducted by Babson Survey Research Group in Fall 2015.

In that survey, only 29.1 percent of chief academic officers said their faculty viewed online education as valuable and legitimate. That’s a slight increase from the year before but a slight decrease from 2004. Granted the drop was only about a point and a half, but I was still surprised that faculty support for online education had declined over the past decade.

Less than two-thirds of those administrators say online education is crucial to their institutions’ long-term strategies. That is a drop from 2014, though considerably above 2002, when less than 50 percent of administrators saw online as an important option.

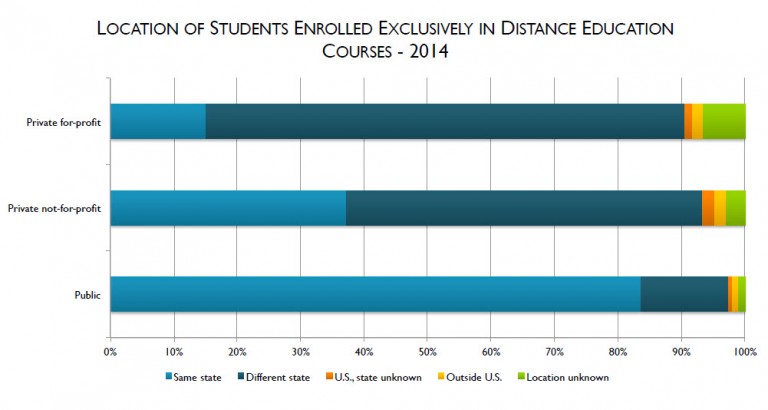

The report said that 28 percent of students were taking at least one online course, and the vast majority of those students were at public universities. The report’s authors write: “It appears that many traditional universities are using online courses to meet demand from residential students, address classroom space shortages, provide for flexible scheduling, and/or provide extra sections.”

Those are all logical, important reasons to pursue online education, yet some universities see their future as solely an in-person enterprise. That may make sense at some level, but failure to experiment with online learning now will only make it more difficult later.

Online learning isn’t a salvation for higher education. In fact, many of us who create and teach online courses see in-person learning as a better option for most students in most courses. Universities need online courses in their repertoire, though. Online courses provide flexible learning options to students, especially during summers and breaks. That flexibility offers a means for keeping students on track toward graduation, and gives them the option of pursuing jobs, internships, and study abroad. Online courses also help faculty and staff members develop expertise in creating materials for hybrid and flipped classes. And perhaps most important, they provide a means for exploring news ways to help students learn.

That’s one reason that the continued resistance to online education is so troubling. It is symptomatic of a recalcitrant attitude toward change. We can deny the holes in the hull all we want, but denial won’t stop the leaks.

What department chairs should say

Maryellen Weimer offers a wonderful wish list of things she wishes department chairs would say about teaching. It includes areas like introducing new faculty to teaching, overusing summative evaluation of teaching, and developing a reward system for innovative teaching.

Here’s one of the favorite wanna-be conversation starters she offers:

[pullquote]“We need to be having more substantive conversations about teaching and learning in our department meetings. We talk about course content, schedules, and what we’re offering next semester but rarely about our teaching and its impact on student learning. What do you think about circulating a short article or article excerpt before some of our meetings and then spending 30 minutes talking about it? Could you recommend some readings?”[/pullquote]

Briefly …

The Scout Report, a newsletter of curated web resources, recently released an excellent special issue on copyright and intellectual property. … The Hechinger Report looks into the 12-hours-as-full-time culture that keeps many students from graduating from college in four years. … Karin Forssell of Stanford suggests that talking about integrating tools rather than technology into teaching “frees teachers from worrying about the intimidation, complication and distraction that ‘technology’ can bring.”

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.