By Doug Ward

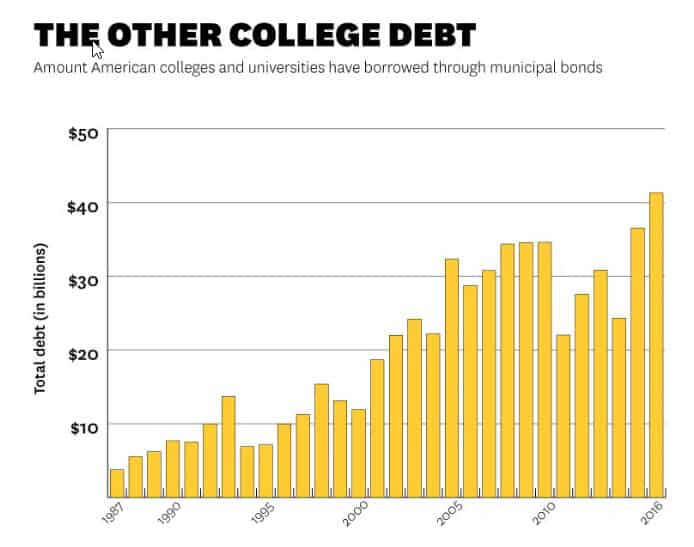

The amount of debt that colleges and universities are taking on is rising even as the number of students in higher education is declining, The Hechinger Report says. It offered these sobering statistics:

Public universities have taken on 18 percent more debt in the last five years, and now owe a collective $145 billion. When you add in private universities, the amount rises to $240 billion. On average, 9 percent of college and university budgets go toward debt payments. At public universities, that amounts to $750 per student. At private universities, $1,289 per student.

KU has certainly followed this borrowing trend. Since 2012, the university has issued $467 million in bond debt, according to Moody’s, the financial ratings company. That includes $350 million in 2015 for work on the Lawrence campus. According to the university budget office, KU paid $22,250,321 toward principal and interest on its outstanding bonds during the last fiscal year. That amounts to $782.17 for every student on the Lawrence, Edwards and medical center campuses, or 4.3 percent more than the average for public universities.

I’ve had a difficult time finding measures comparable to those that Hechinger cited, but budget office figures show that debt service accounted for 2.5 percent to 3 percent of total expenditures at KU in Fiscal 2016.

Debt isn’t necessarily a cause for concern. When used for construction, it becomes a bet on the future, much as investment in a house is. KU desperately needed to update its science facilities and some of its aging residence halls. It still desperately needs to modernize hundreds of classrooms and create additional spaces for collaborative learning. The sad reality is that it’s easier to raise money for new buildings than it is to raise money to renovate existing ones.

Hechinger’s point is that increased borrowing has put some universities on shaky financial ground, especially as the number of students enrolled in college has fallen by 2.4 million since 2011. Rising levels of debt increase overall expenses, often contributing to higher tuition rates.

Universities face a conundrum, though. States have drastically cut back on the amount they have contributed to universities and have done a poor job of providing adequate money for upkeep of existing buildings. At the same time, universities feel pressure to keep up with their peers, especially at a time when recruiting students often involves wowing them with campus amenities. This is all part of a commercialization of higher education, with the product and image of education overshadowing the importance of learning.

Moody’s has raised concern about KU’s accumulation of debt, listing the university’s outlook as negative for the last two years. That means the university’s bond rating could be downgraded, raising the cost of borrowing. Moody’s said the “negative outlook reflects the challenge of growing revenue and cash flow to support increasing operating and capital expenses associated with a large campus expansion.”

Whether that expansion will pay off, either financially or in terms of learning, remains to be seen.

Alternative credentials gain momentum

The approach makes sense even if the names don’t.

EdSurge reports that EdX, which offers massive open online courses from Harvard and MIT, has begun what it calls “micromasters” degrees. These involve five courses that cover about 30 percent of a traditional degree. It received a $900,000 grant last year from the Lumia Foundation to develop 30 such programs. Another MOOC provider, Udacity, has created what it calls “nanodegrees” in mostly technology-related areas, EdSurge says.

The names are certainly a marketing ploy, but the move to offer alternative credentials follows a growing trend. If colleges and universities are truly about lifelong education, they need to do better at providing options beyond traditional degrees. Many, including KU, have been increasing the number of certificates they offer, and some organizations have been experimenting with badges. Demand for education at the master’s level has been growing, generating much-needed revenue for universities.

EdSurge quotes Michael DiPietro, chief marketing officer of ExtensionEngine, which creates online course components. He says educators need to move beyond the idea of shifting in-person classes online and start thinking of microcredentials as a business venture. He says:

“Start with a business plan—one that outlines the market, learner personas, competition, revenue and cost projections, team and operational resources, ecommerce, positioning, differentiators, and more. Your product — the program, course, certificate, or degree — has to be unique and very specific to what your market wants.”

The idea of a degree or certificate as a business plan is certainly off-putting to those of us who see education as a public service, but he’s right that education must change as the needs of potential students change. That doesn’t diminish the importance of a liberal education. It just means we need to think in new ways about the types of courses, degrees and certificates we offer.

Briefly …

Drexel University gave incoming students backpacks made with a new fabric that can store digital information, CBS News reports. Students used the backpacks and an accompanying app to share their social media profiles at the beginning of the school year. … University instructors have become so paranoid about cheating that they are hampering learning, Bruce Macfarlane argues in Times Higher Education. … The New York Times Magazine delves into the causes and implications of an epidemic of anxiety afflicting students in high school and college.

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.