If you are sitting on the fence, wondering whether to jump into the land of generative AI, take a look at some recent news – and then jump.

- Three recently released studies say that workers who used generative AI were substantially more productive than those who didn’t. In two of the studies, the quality of work also improved.

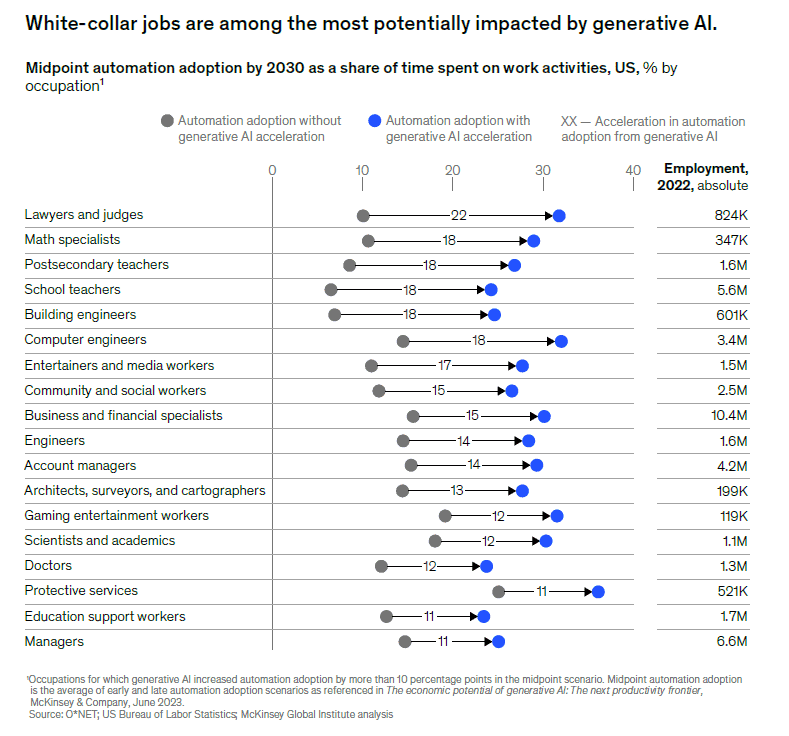

- The consulting company McKinsey said that a third of companies that responded to a recent global survey said they were regularly using generative AI in their operations. Among white-collar professions that McKinsey said would be most affected by generative AI in the coming decade are lawyers and judges, math specialists, teachers, engineers, entertainers and media workers, and business and financial specialists.

- The textbook publisher Pearson plans to include a chatbot tutor with its Pearson+ platform this fall. A related tool already summarizes videos. The company Chegg is also creating an AI chatbot, according to Yahoo News.

- New AI-driven education platforms are emerging weekly, all promising to make learning easier. These include: ClaudeScholar (focus on the science that matters), SocratiQ (Take control of your learning), Monic.ai (Your ultimate Learning Copilot), Synthetical (Science, Simplified), Upword (Get your research done 10x faster), Aceflow (The fastest way for students to learn anything), Smartie (Strategic Module Assistant), and Kajabi (Create your course in minutes).

My point in highlighting those is to show how quickly generative AI is spreading. As the educational consultant EAB wrote recently, universities can’t wait until they have a committee-approved strategy. They must act now – even though they don’t have all the answers. The same applies to teaching and learning.

A closer look at the research

Because widespread use of generative AI is so new, research about it is just starting to trickle out. The web consultant Jakob Nielsen said the three AI-related productivity studies I mention above were some of the first that have been done. None of the studies specifically involved colleges and universities, but the productivity gains were highest in the types of activities common to colleges and universities: handling business documents (59% increase in productivity) and coding projects (126% increase).

One study, published in Science, found that generative AI reduced the time professionals spent on writing by 40% but also helped workers improve the quality of their writing. The authors suggested that “ChatGPT could entirely replace certain kinds of writers, such as grant writers or marketers, by letting companies directly automate the creation of grant applications and press releases with minimal human oversight.”

In one of two recent McKinsey studies, though, researchers said most companies were in no rush to allow automated use of generative AI. Instead, they are integrating its use into existing work processes. Companies are using chatbots for things like creating drafts of documents, generating hypotheses, and helping experts complete tasks more quickly. McKinsey emphasized that in nearly all cases, an expert oversaw use of generative AI, checking the accuracy of the output.

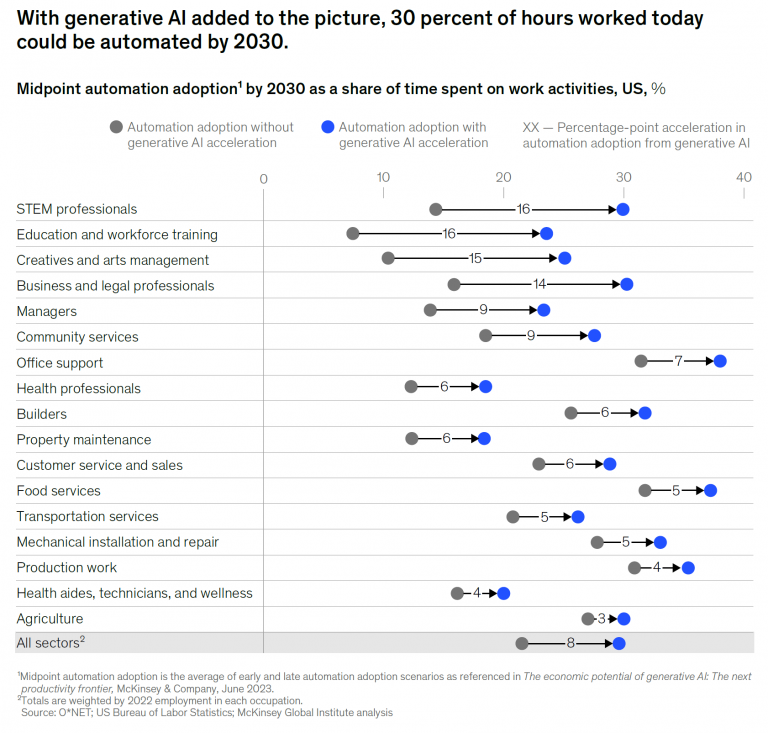

Nonetheless, by 2030, automation is expected to take over tasks that account for nearly a third of current hours worked, McKinsey said in a separate survey. Jobs most affected will be in office support, customer service, and food service. Workers in those jobs are predominantly women, people of color, and people with less education. However, generative AI is also forcing changes in fields that require a college degree: STEM fields, creative fields, and business and legal professions. People in those fields aren’t likely to lose jobs, McKinsey said, but will instead use AI to supplement what they already do.

“All of this means that automation is about to affect a wider set of work activities involving expertise, interaction with people, and creativity,” McKinsey said in the report.

What does this mean for teaching?

I look at employer reports like this as downstream reminders of what we in education need to help students learn. We still need to emphasize core skills like writing, critical thinking, communication, analytical reasoning, and synthesis, but how we help students gain those skills constantly evolves. In terms of generative AI, that will mean rethinking assignments and working with students on effective ways to use AI tools for learning rather than trying to keep those tools out of classes.

If you aren’t swayed by the direction of businesses, consider what recent graduates say. In a survey released by Cengage, more than half of recent graduates said that the growth of AI had left them feeling unprepared for the job market, and 65% said they wanted to be able to work alongside someone else to learn to use generative AI and other digital platforms. In the same survey, 79% of employers said employees would benefit from learning to use generative AI. (Strangely, 39% of recent graduates said they would rather work with AI or robots than with real people; 24% of employers said the same thing. I have much to say about that, but now isn’t the time.)

Here’s how I interpret all of this: Businesses and industry are quickly integrating generative AI into their work processes. Researchers are finding that generative AI can save time and improve work quality. That will further accelerate business’s integration of AI tools and students’ need to know how to use those tools in nearly any career. Education technology companies are responding by creating a large number of new tools. Many won’t survive, but some will be integrated into existing tools or sold directly to students. If colleges and universities don’t develop their own generative AI tools for teaching and learning, they will have little choice but to adopt vendor tools, which are often specialized and sold through expensive enterprise licenses or through fees paid directly by students.

Clearly, we need to integrate generative AI into our teaching and learning. It’s difficult to know how to do that, though. The CTE website provides some guidance. In general, though, instructors should:

- Learn how to use generative AI.

- Help students learn to use AI for learning.

- Talk with students about appropriate use of AI in classes.

- Experiment with ways to integrate generative AI into assignments.

Those are broad suggestions. You will find more specifics on the website, but none of us has a perfect formula for how to do this. We need to experiment, share our experiences, and learn from one another along the way. We also need to push for development of university-wide AI tools that are safe and adaptable for learning.

The fence is collapsing. Those who are still sitting have two choices: jump or fall.

AI detection update

OpenAI, the organization behind ChatGPT, has discontinued its artificial intelligence detection tool. In a terse note on its website, OpenAI said that the tool had a “low rate of accuracy” and that the company was “researching more effective provenance techniques for text.”

Meanwhile, Turnitin, the company that makes plagiarism and AI detectors, updated its figures on AI detection. Turnitin said it had evaluated 65 million student papers since April, with 3.3% flagged as having 80% to 100% of content AI-created. That’s down from 3.5% in May. Papers flagged as having 20% or more of content flagged rose slightly, to 10.3%.

I appreciate Turnitin’s willingness to share those results, even though I don’t know what to make of them. As I’ve written previously, AI detectors falsely accuse thousands of students, especially international students, and their results should not be seen as proof of academic misconduct. Turnitin, to its credit, has said as much.

AI detection is difficult, and detectors can be easily fooled. Instead of putting up barriers, we should help students learn to use generative AI ethically.

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications.