By Doug Ward

Randy Bass sees a struggle taking place in higher education.

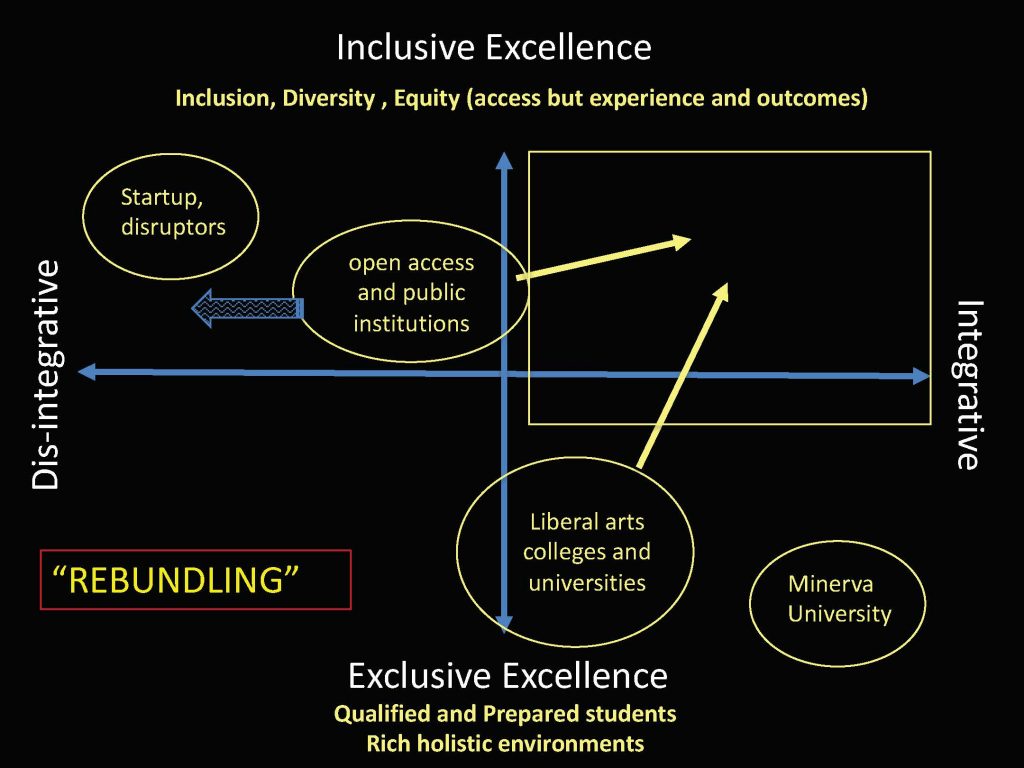

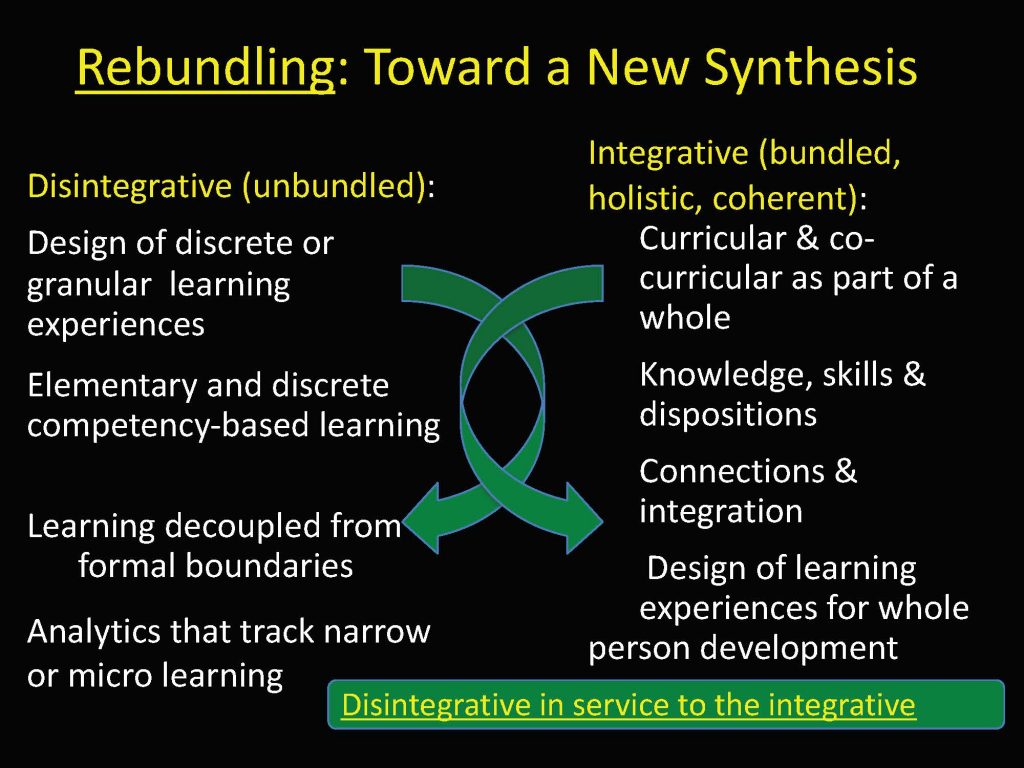

On one side are those who see the future as “unbundled,” a model in which students pursue discrete skills at their own pace and mostly under their own direction. On the other side are those who see the future as bundled, much as a university is now with classes and programs and a physical environment that draws everything together.

This is not a clash of right vs. wrong or good vs. evil, Bass, a professor and administrator at Georgetown University, said in his keynote address at KU’s annual Teaching Summit this month. The bundled model needs the skills, flexibility and other elements of the unbundled side, he says, although he contends that those pursuing the unbundled model “are working with a diminished vision of education.”

Let’s tease those elements apart a bit.

The unbundled model that Bass describes has been embraced by many entrepreneurs and authors who see the traditional model of higher education failing. Under this model, classes have little or no ties to each other and learning is detached from physical spaces. Students focus on particular skills when they need them, work at their own pace and learn on their own, often online. Bass describes this approach as “granular, targeted, modular.” Competency-based education lives on this side of the spectrum. So do MOOCs and online organizations like Lynda.com and Kahn Academy. It is driven by analytics and takes what Bass calls a “disintegrated” approach to learning, one that its advocates say will help underserved populations.

The bundled model approaches higher education as a community. Classes, at least in theory, build on and integrate with each other, helping students accumulate expertise that leads toward completion of a degree. This approach works toward whole-person education, Bass said, providing interaction with other students and with instructors. It builds in skills like critical thinking, creativity, empathy and ethical judgment. All of this is integrated into a larger learning community located in a particular physical space: classrooms, living spaces, informal spaces, and a physical campus. It involves things like student organizations, sports, and arts and entertainment.

He called on universities to work at “rebundling” education in more meaningful ways, finding opportunities to integrate skills and to allow students to work on difficult, authentic questions from the beginning of their studies. The future of higher education, he said, depends on our ability to bring together the components of the unbundled and bundled models of education.

“These two discourses have largely been separate and at war and talking past each other until the last few years,” Bass said. “The great challenge of the next decade or more is to move toward a new synthesis.”

This new synthesis is crucial, Bass says, because higher education will undergo big changes in the next couple of decades. He drew on the biological theory of punctuated equilibrium, which suggests that evolution doesn’t take place in a steady progression. Rather, it goes through long periods of stability punctuated by big leaps in changes of life forms.

“I think we’re in that period of time in higher education,” Bass said. “I think the last 15 to 20 years have been building to it. … It’s creating a shift in what we consider the species of how we deliver higher education. Over the next 15 years, there’s going to be a jump, a shift in the landscape.”

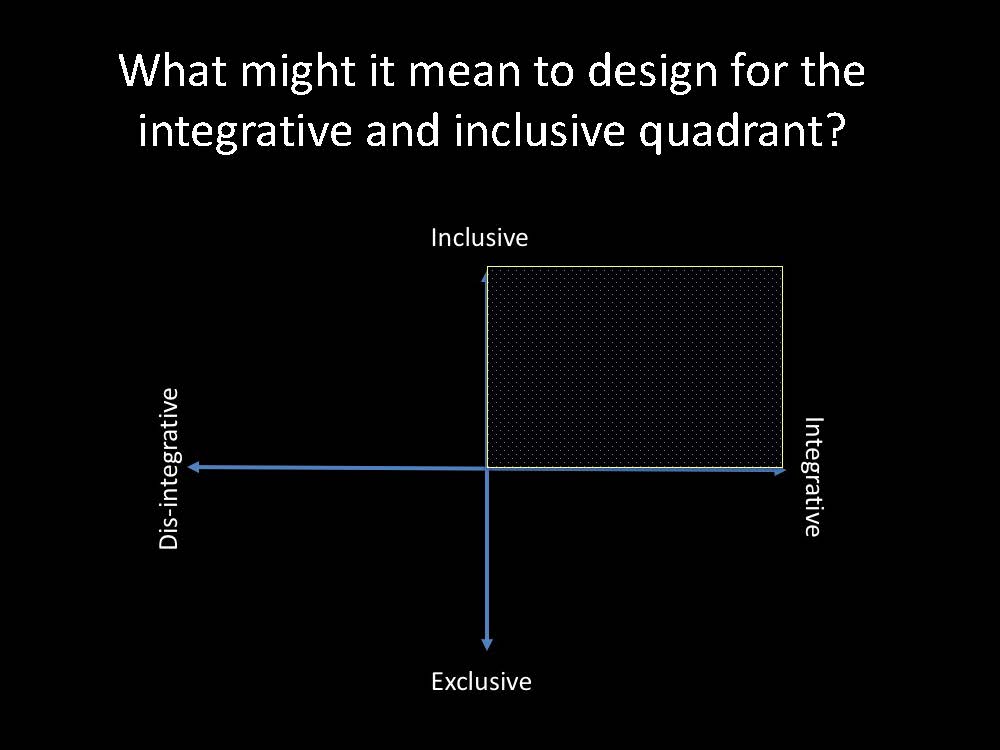

He made a case that the future lies at the intersection of inclusiveness and integration. It involves integrating the skills promoted by those who want to unbundle education but integrates what Bass called “hard skills”: learning to learn, critical thinking, creativity, curiosity, resilience, empathy, humility, ethical judgment.

“We also know that we can’t teach most of those things directly,” Bass said. “We can’t teach these as direct instruction. But we can design environments where they are more likely rather than less likely to be cultivated.”

Universities were founded on the idea of exclusive excellence, he said, and much of higher education still operates on this model. The future, though, depends on our ability to provide inclusive excellence, he said, to find ways to draw in more people into high-quality, integrative education.

To help with that, he urged adoption of high-impact practices, which have been shown to improve student success. These practices help create unscripted environments that provide hands-on learning, push students outside their comfort zone, help them learn more about themselves, and allow disparate components of education to come together. (What’s the opposite of high-impact practices? That would be low-impact practices, he joked, “otherwise known as the curriculum.”)

The future depends on helping students accept uncertainty and to learn to think like experts in their disciplines. It also depends on instructors, disciplines and universities identifying what they want students to take away from classes, curricula and a university education.

“If it matters, you have to make it integral,” Bass said.

We also need to redesign and expand what we mean by rigor, Bass said. One thing that draws people into a discipline, he said, is that they fall in love with what’s difficult about that field.

“The most important thing we can do, as early as possible and with as many people as possible, is to introduce them to how to navigate difficulties and appreciate difficulty and uncertainty.”

Bass offered examples of what that might look like. One involved a student project from a class he teaches on the future of the university. That model envisions education as a community of peers working to gain experience, expertise and independence as students’ thinking grows in complexity. It emphasizes a “profound sense that college should build to something that makes you really capable,” Bass said.

Another, in which he went into more depth, was a biology class his wife taught that involved at-risk students in a project that analyzed the soil and environment of a Virginia winery. The project humanized learning by having students take on a challenge that involved real-world problems in a location that students got to know well.

Both of those models follow his ideal of education as inclusive and integrative. There are many ways of moving into that realm, he said, and we must keep experimenting. Bass said a biologist reminded him that in a period of punctuated equilibrium, 99 percent of all lifeforms die. In the case of higher education, those “lifeforms” are colleges, universities, departments, programs and individual faculty members.

“There will be institutions to whom change is done, and there will be institutions in control of that change,” Bass said.

Throughout his talk and in workshops that followed, Bass pushed instructors, staff members and administrators to think about ways of staying in front of potentially destructive change.

“The question is,” he said, “how do we as higher ed institutions survive and thrive during this shift?”

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.