Alternative Grading: A Teaser

For anyone wanting the quick primer on alternative grading, this is for you! Alternative grading is a set of practices that refocus student attention to learning and away from points or grades. Moreover, alternative grading is not an all-or-nothing proposition; you can start small. After looking through this quick overview, faculty are encouraged to explore more comprehensive resources, such as

Blogs: More prominent examples include Clark & Talbert's Grading for Growth Blog. Jesse Stommel also has a primer on How to UNgrade.

Books: Many are available, and a few great places to start are Blum's "UNgrading," Clark & Talbert's "Grading for Growth," and Nilson's "Specifications Grading." Full references for these can be found at the bottom of this page.

Conferences: The Center for Grading Reform hosts The Grading Conference, a virtual conference in early summer very worth attending (and happily convenient.)

Podcasts: Krinsky and Bosley initiated The Grading Podcast in 2023, interviewing faculty the globe over who use alternative grading approaches in a variety disciplines, course formats, and class sizes.

Websites: UNL has a detailed website with references to primary literature, and use of a search engine will turn up countless other great resources.

KU's Reframing Grading Forum: In spring 2025, KU hosted its first Reframing Grading Forum, which provided opportunities all faculty: those wanting to hear more about it from an expert, those wishing to dip their toes in, and those trying to hone their alternative grading craft. This resulted in a web resource from the 2025 Forum. It's a great place for actionable information.

What It Is by What It Is Not

Alternative grading is an umbrella term for evaluation methods that stand in contrast to traditional grading systems, wherein students accumulate points or letter grades on each assignment throughout the semester that culminate in a final course grade. Many instructors have had the experience of students haggling for individual points or pleading for “just a small bump up,” leading to the sense that students are more focused on grades than learning. And realistically, they should: We set them up to do so. We can’t (or shouldn’t) create systems of artificial and extrinsic rewards (like points) and simultaneously question why students aren’t intrinsically motivated by the skills and content of the course; this is unfair and short-sighted. Alternative grading methods are meant to shift student focus away from grades and toward learning by deconstructing traditional grading systems, at least in part and often in their entirety. Enticing, no?

Familiar(ish) Examples

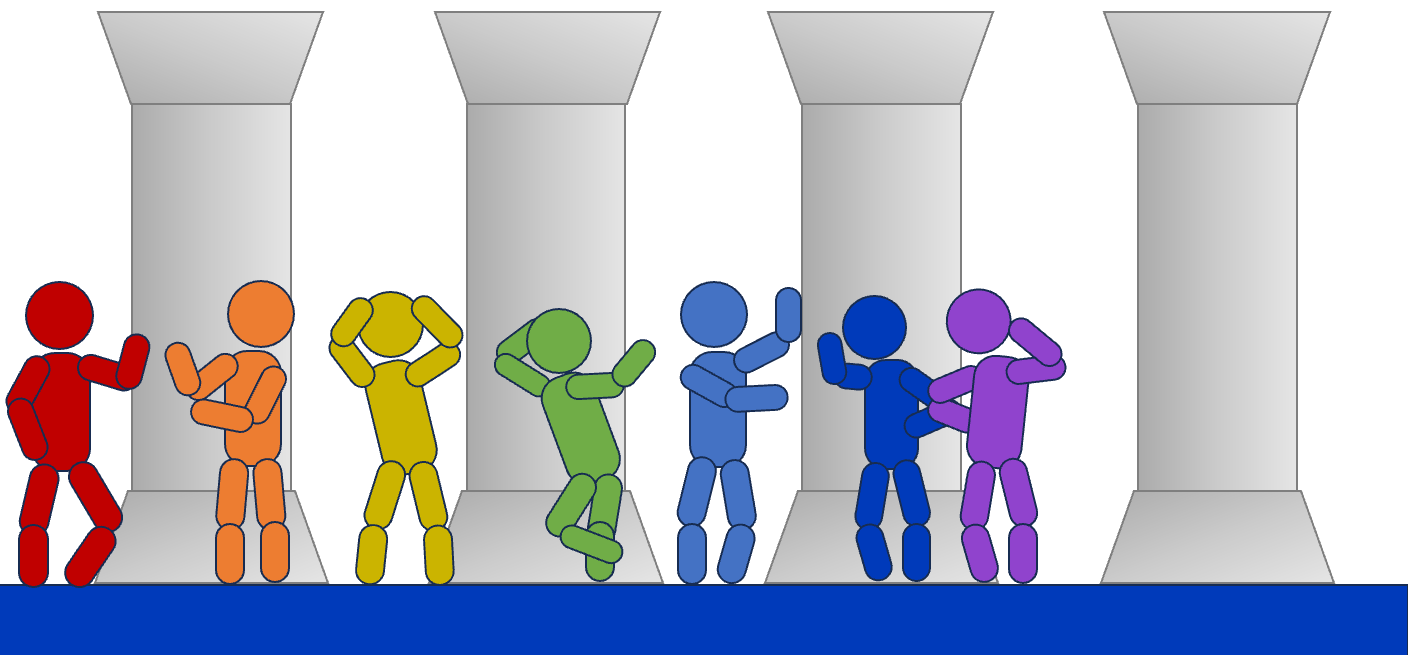

While alternative grading encompasses any method that better orients students toward learning over grades, several well-described lineages of effort have gained traction among faculty in recent years. Note that some of these systems are highly related to one another: Competency-, mastery-, specifications-, and standards-based grading can be thought of as one clade of alternative grading. If game-based and gamified learning are fraternal twins, contract- and labor-base grading are kissing cousins. UNgrading may be that character revealed to be related to everyone and garnering heightened attention. Treat the descriptions below as impressionist portraits rather than sharp photographs.

Alternative Grading Examples:

Competency-Based Grading or CBG: Specific competencies (skills or knowledge in the course) are developed (sometimes based on industry standards) and tied directly to course outcomes. (Each outcome typically houses several competencies.) Students can reattempt assessments, with the instructor indicating progress using a binary system: not met/net, not yet/pass, reattempt/move on, etc. Often, a course grade is derived from the number of competencies the student has demonstrated.

Contract Grading: Much like what it sounds, students and the instructor collaborate to determine one or more important parameters of the course: what constitutes quality, how many assignments should be completed, how many revisions are allowed, how many assignments can be missed, what to do about absences, what happens under breach of contract, etc. Most importantly, they decide what will constitute different letter grades at the end of the term, and which grade they’ll try to earn. Feedback is robust and regular, often through viz-a-viz consultations, and contracts can be modified partway through the semester. Contracts can be developed with students at the individual, group, or course level. The upside is the enhanced clarity of these systems and the agency students have in selecting a grade to strive for.

Game-Based LearningGBL: Distinct from gamification, game-based learning embeds one or more games—established or invented—as the basis for learning. The idea in game-based learning is that the game provides the context in which students apply various skills or knowledge. Formats are unrestricted: Think role-playing games, online games, card games, board games, strategy games, and more. As an example, students learning the basics of epidemiology and disease dynamics in a biology course might play the board game “Pandemic,” and, after familiarizing themselves with the mechanics through several rounds of play, they dissect how the game does and does not reflect reality. Perhaps they go further to create new mechanics that add some missing realism. These systems often leverage productive failure as the primary form of learning. Somewhat obviously, the games and how students think about them should be directly aligned to the course’s learning outcomes.

Gamification: Distinct from game-based learning, gamification applies the mechanics of board or other gaming systems to a course’s entire structure. Two important features that are usually present: 1) Students are allowed reattempts and 2) There are multiple pathways for students to succeed. In contrast to many other alternative grading approaches, this system leans into extrinsic rewards but in entertaining or otherwise meaningful ways. Students might go on “quests” that lead them to acquire particular skills, earn badges or tokens that symbolize accomplishment, “level-up” in a tiered system of difficulty or effort, see their relative progress on a leaderboard, etc. At its best, a created narrative helps students “suspend reality” and fully buy in to the system.

Labor-Based Grading: Labor-based grading recognizes that prior learning and resources vary considerably among students. In this system, grades emphasize student labor, as reflected in time-on-task, task completion, and process as documented by the student through such mechanisms as work logs, reflection pieces, work-in-progress (drafts), etc. Note that the grades are often pre-negotiated with the instructor in the form of a contract: what constitutes labor and how much labor results in which course grade. Feedback tends to be tailored and narrative, with students moving from “incomplete” to “complete” status on assignments. This can be an attractive option where process has the same or greater value as product, such as arts and humanities.

Mastery Grading: This involves the instructor declaring a threshold of performance or mastery for student work (e.g., 80%), and students may not move to the next item in the course until they meet this threshold; multiple, if not unlimited, reattempts are permitted. Mastery grading is often encountered in asynchronous online courses, where the pace of learning is set by the student, rather than the instructor. That said, mastery grading can be used in any context. It is imperative in these schemes that students encounter simpler, supporting skills and knowledge before moving onto more advanced skills and knowledge in the course. Accordingly, instructors might think deeply about hierarchies of cognition, such as Bloom’s taxonomy.

Specifications Grading or "specs" grading: Specifications grading is a competency-based system (see above) that emphasizes student agency. Assignments are “bundled” into groups that signal different levels of achievement, and students select the bundles they wish to complete. Assignments come with a detailed set of specifications (standards.) Feedback on individual assignments is binary (e.g., not yet/pass), along with an indication (often just a circling) of which specifications were unmet. Generally, completing larger and more challenging bundles is connected to a higher course grade. Note that reattempts on assignments are limited and involve a token system, making specifications grading attractive for moderate- to high-enrollment courses.

Standards-Based Grading or SBG: This is nearly synonymous with competency-based grading. The standards instructors develop at the course level (course outcomes, standards for individual assignments) are often tied to external educational standards (professional accreditation standards, state education standards, etc.) SBG also often involves graduated systems of simple feedback, so students have a better sense of progress. A common system is “beginning,” “developing,” “proficient,” and “advanced.”

UNgrading: Much like it sounds, ungrading eliminates points, letters, or other simple and declarative marks from individual assignments. Robust and regular feedback comes from the instructor, peers, and self; a prevalent structure in UNgrading is one-on-one consultations with the instructor. UNgrading recognizes that learning is constructed. To that end, students monitor their progress in an instructor-supported way through reflection prompts, learning journals, feedback logs, etc. Often, they refer to a portfolio of their work to recognize and showcase their growth. Final course grades are generally determined in collaboration with the instructor, with the student offering evidence of learning in their portfolio.

The Four Pillars: A Framework

Clark & Talbert have expertly distilled common features of alternative grading from the milieu of work done so far: The Four Pillars (Clark & Talbert, 2023). This framework is concise, providing the minimum substance for new grading alchemists. Moreover, instructors can start small, introducing just a little at a time to their course, with significant benefit to students. The Four Pillars are reproduced in short below, but for richer description, their book "Grading for Growth" is a tremendous resource.

Clearly Defined Standards

This has a few components: (1) Identify and list what matters in the course. Then edit, striking the extraneous. (2) Create high standards. Common advice is to write standards to B-level work. (3) Use plain language. If students can't understand your standards, they can't meet them. (4) Create a reasonable number. Between student work and your evaluation of it, this is practical advice. The tight scope also clarifies the course.

Helpful Feedback

Feedback to students should help them move forward in productive ways. This includes suggesting paths for improvement. It ALSO includes highlighting strengths, so students know what to keep doing. Feedback should remain focused on progress toward the standards. Don't stray!

Marks Indicate Progress

Any marks provided to students should be an indicator of their progress or growth. Keep any marks short and consistent, so students know what they mean. These should support, not substitute for, feedback. A system like "beginning," "developing," "proficient," and "advanced" works, as does "not yet" / "pass". A numeric indicator like "3/5 met" might direct students to feedback on the 2 unmet standards. It does not, however, constitute a score toward a final grade.

Reattempt Without Penalty

Students are able to resubmit work multiple times without cost to them. In many common systems, reattempts are unlimited. Succinctly, improvement based on feedback IS learning, making reattempts key. Students should be able to do this freely. "Can resubmit with 10% deduction" and similar statements disincentivize learning and refocus student attention on the grade, thereby undercutting the instructor's own work in teaching.

References and Resources

Blum, S. D. (Ed.). (2020) UNgrading: Why Rating Students Undermines Learning (and What to Do Instead) West Virginia University Press.

Clark, D., Talbert, R. (2023) Grading for Growth: A Guide to Alternative Grading Practices that Promote Authentic Learning and Student Engagement in Higher Education. Routledge.

Clark, D., Talbert, R. (2021) Podcast: Grading for Growth. https://gradingforgrowth.com/

Krinsky, S., Bosley, R., Lewis, A. (Organizers) 2020, The Grading Conference. https://www.centerforgradingreform.org/grading-conference/

Krinsky, S., Bosley, R. (Hosts), 2023, The Grading Podcast. https://thegradingpod.com/

N/A, “Alternative Grading for College Courses.” University of Nebraska-Lincoln. 2025. https://teaching.unl.edu/resources/alternative-grading/ (Accessed Feb. 24, 2025).

Nilson, L. B. (2015) Specifications Grading: Restoring Rigor, Motivating Students, and Saving Faculty Time. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Stommel, J. (Mar. 11, 2018) How to Ungrade. JesseStommel. https://www.jessestommel.com/how-to-ungrade/