Reframing Grading Forum 2025

This is the highlight reel from the 2025 Reframing Grading Forum hosted by CTE and featuring Sharona Krinsky. Here, you'll find:

- Recordings of the Sharona's morning keynote, which challenges traditional grading practices from a mathematical perspective.

- Resources from Sharona's afternoon workshop, which poses questions faculty should work through when developing an alternative grading system of their own.

- Facets of the program that faculty participants found most exciting.

- Questions that lingered for faculty, along with resources to address these questions as a way of follow-up to the Forum.

Keynote Recording

The keynote address "Grading: The (Mis)use of Mathematics in Measuring Student Learning" with its narration and participation can be found below. The session was interactive. Participants worked through key tasks, and you're encouraged to pause the video and do the same.

The keynote slides only—no narration—are available here. These should be considered at-a-glance information only, as they can't substitute for the rich insight in the link above.

Workshop Resources

The workshop slides only—no narrative—are available here. Like the keynote, this should be considered cursory information and does not substitute for the full experience.

The working document has also been shared with us. Note that you'll need to download a local copy to work from it. Access it here.

What Excited Participants

Forum participants were asked to completed an "exit ticket" before departing. One question was "What did you learn that excites you the most?" Their responses (dropdown headings below) were recorded and then organized into themes with the help of AI. Selected themes and responses have been elaborated upon (not using AI) in the dropdown text.

The emergent themes were

- Conceptual Shifts: Several participants enjoyed the scrutiny of longstanding and little-challenged practices. (Very academic!)

- Practical Implementation Ideas: Faculty latched onto ideas that streamline the work of adjusting their grading systems.

- Systemic Benefits: The crowd appreciated direct and indirect communication about the benefits of alternative grading approaches that help all learners in a course.

Conceptual Shifts

Traditional grading systems have their roots in promoting disparity and continue to do so today. If the only purpose of a grade is sorting of students by prior learning and ability to learn quickly, traditional grading works well. When pressed, though, most instructors suggest their grades are meant to show a student's facility with a course's knowledge or skills. For that purpose, traditional grading systems conflate multiple abilities under a single and uninterpretable measure, prohibit students from showing delayed learning, and make a actual student's learning in the course opaque to the instructor, other stakeholders, and worst of all, the students themselves.

Instructors often use numbers as categorical data that reflect learning: Student performance is translated to a numeric score. For example, a 7 or an 8 out of 10 is probably meant to signal "good." Instructors then take those categorical data and calculate with them (think averages, standard deviations, and more) because these categorical data are now in the form of numbers. The practice isn't an instructor's fault; the conflation is easy because the representation is ambiguous. The result, however, is a longstanding and fundamental misapplication of statistics to numerically-represented categorical data. Ask yourself: What is the average of "good," "well done!" and "this needs work?" across three different content areas and tasks?

A couple examples highlighted the fact that averages serve as a poor indicator of performance. (Look for the parachute packer example in her talk!) If what we want to know is "Can the student do this part of my course?" an average will penalize late learning and obscure the answer. While there are no perfect systems, there are better ways to answer this question, including (but not limited to) using a student's last attempt or best attempt.

What does a grade do, anyway? Several participants valued this challenge and used a template to answer this very question:

The purpose of my grades is to ___(1)___ ___(2)___ to ___(3)___.

- What action are your grades meant to perform? Choose a strong verb.

- What academic or non-academic factors receive this action? Choose an object the verb acts upon.

- Who is the intended audience? Choose a specific group.

The keynote includes an example. Try this yourself, and answer: What does a grade from you do?

Practical Implementation Ideas

A few faculty prized the PPP system described during the talk. PPP is preparation / participation / practice. In Sharona's system, PPP stands alongside the course standards as its own "bucket." Students accumulate points in a way familiar to most faculty, and the points are awarded to students based on—you guessed it—the student's preparation, participation, and practice throughout the semester. The standard is met when students accumulate 750-ish of 1200-ish points, and that met standard can contribute to their final course grade. In this way, the PPP standard for the course might be considered an aggregated standard for soft skills—students learning "how to student" through the type of learning actions instructors value.

Participants felt reassured that they could, like the keynote speaker, develop alternatively graded courses within the Canvas architecture available to us. Obviously, this can help streamline the implementation of alternative grading systems. Note, though, that there may be a learning curve up front. See below for more details.

Most instructors have, at this point, had some reckoning with learning outcomes or other declarations of our values for student learning. During the Forum, one participant made a particularly salient point: observability and measurability are not the same (at least in the context of our discussion.) When it comes to learning, observability is a necessary but insufficient condition for measurability. We might broadly observe students in the process of learning, but need an artifact of that learning behavior (e.g., a product) to measure. Our learning standards must be measurable in order to take on real meaning.

Such a small shift with such a big effect: Start your goals for students (outcomes, standards, specifications, etc.) with two words. "I can." Students immediately know that these goals are for them, not for a theoretical audience. Upon achievement of the goal, students get a boost, and the affirming language can motivate subsequent learning in the course.

Systemic Benefits

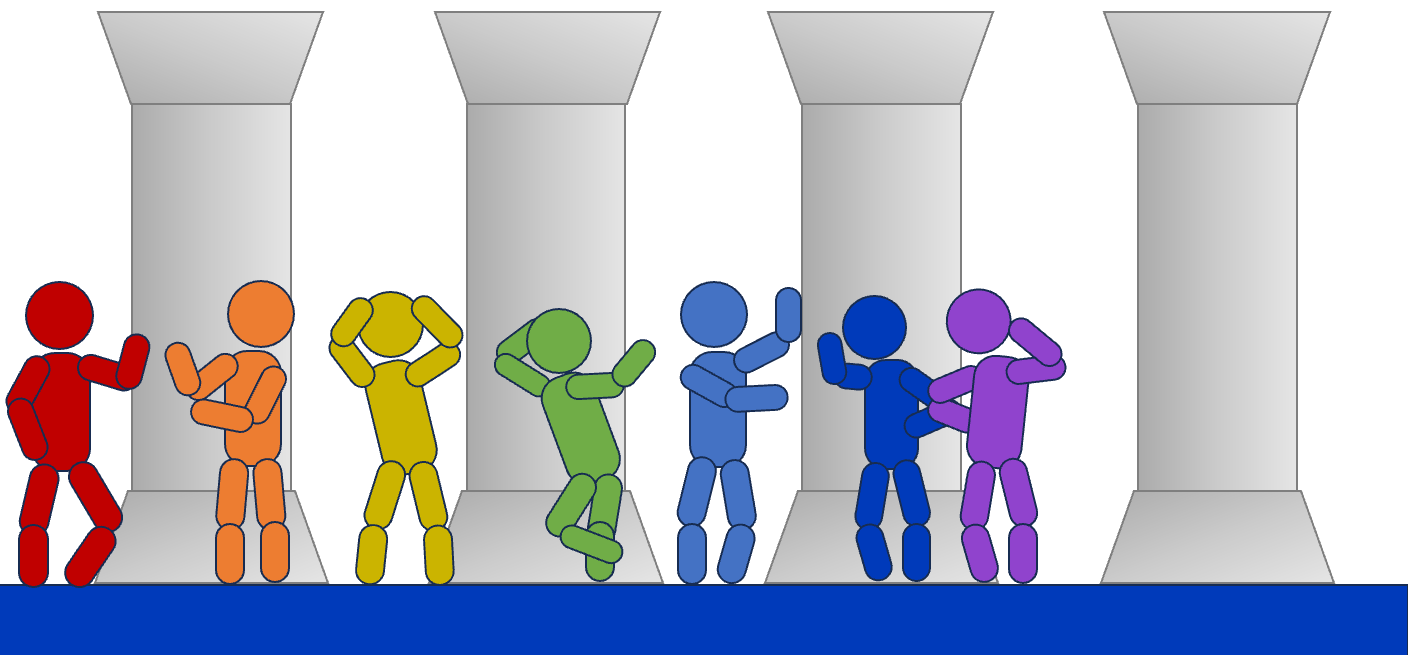

Several faculty felt relief when they realized that "alternative grading" is not a single, monolithic practice. Instead, "alternative grading" is any practice that reduces aggregated points-based notions of learning in one-off attempts in favor of increasing disaggregated and qualitative notions of learning progress over time and across effort—a long way to say it's "The Wild West" of grading. That said, four guiding principles—the "four pillars" model of Clark and Talbert—have emerged from the milieu of work in this area and can be used by faculty when making adjustments to (or even redesigning) a course.

A significant drawback to traditional grading systems is the one-and-done demonstration of learning. There are a couple facets to this:

- If a student can't recover (mathematically, in terms of their course grade) from early failures in a course, why would they continue putting effort toward learning in the course?

- Persistence is a "soft skill" worth developing in today's students and can be codified as a learning outcome in a course. However, this only works if structures are in place to allow for persistence on a task.

One of the pillars of alternative grading is to allow students repeated attempts on a task without penalty. This helps students develop persistence and to continue to the end of a course.

Faculty appreciated that alternative grading—and specifically its "four pillars" (clear standards, meaningful feedback, marks for progress only, and reattempts without penalty)—can help all students. And we might be sympathetic to this form of learning. It's what most of us have come to rely upon after school and in our adult lives. It honors the fact that none of us learn without struggle or failure accompanied by the opportunity to improve or correct. Alternative grading whendone right reveres authentic learning processes.

What Questions Remain?

As part of the "exit ticket" participants also answered "What is your most important outstanding question?" These are similarly summarized below, and where possible, resources to address these questions are offered in the dropdown menus.

The emergent themes were

- Scaling to large courses: How do you start with and incorporate these approaches in large-enrollment courses (e.g., 100+ students), including those with teaching assistants?

- Student experience: What is the student experience in courses that use alternative grading? What are the concerns?

- Technical implementation: How does alternative grading dovetail with Canvas, its features and limitations?

How do we scale alternative grading methods to fit courses with large enrollments (100+ students) and multiple TAs?

Below a short video with some high-level thoughts on scaling alternative grading to large courses. For specifics on methods or for a thought partner in this work, don't hesitate to reach out.

What is the student experience in courses that use alternative grading?

This varies widely by student and course, but many students though mid-semester evaluations, course evaluations, surveys, and reflection pieces report positive experiences. Look for a video soon that highlights KU faculty who use alternative grading in their courses. In it, they'll describe what they observe in their students and recount what their students have told them directly about the experience.

How does alternative grading dovetail with Canvas?

Sharona kindly shared a recorded response to just this question. The video below walks the audience through how she sets up her alternatively graded courses in Canvas.

References and Resources

Clark, D., Talbert, R. (2023) Grading for Growth: A Guide to Alternative Grading Practices that Promote Authentic Learning and Student Engagement in Higher Education. Routledge.

Krinsky, S., Bosley, R., Lewis, A. (Organizers) 2020, The Grading Conference. https://www.centerforgradingreform.org/grading-conference/

Krinsky, S., Bosley, R. (Hosts), 2023, The Grading Podcast. https://thegradingpod.com/

Nilson, L. B. (2015) Specifications Grading: Restoring Rigor, Motivating Students, and Saving Faculty Time. Stylus Publishing, LLC.