By Doug Ward

This year’s update on the Kansas Board of Regents strategic plan points to some difficult challenges that the state’s public colleges and universities face in the coming years.

First, the number of graduates is thousands short of what the regents say employers need each year. The number of certificates and degrees among public and private institutions actually declined by 1.2 percent between 2014 and 2018, and was 16 percent short of the regents’ goal.

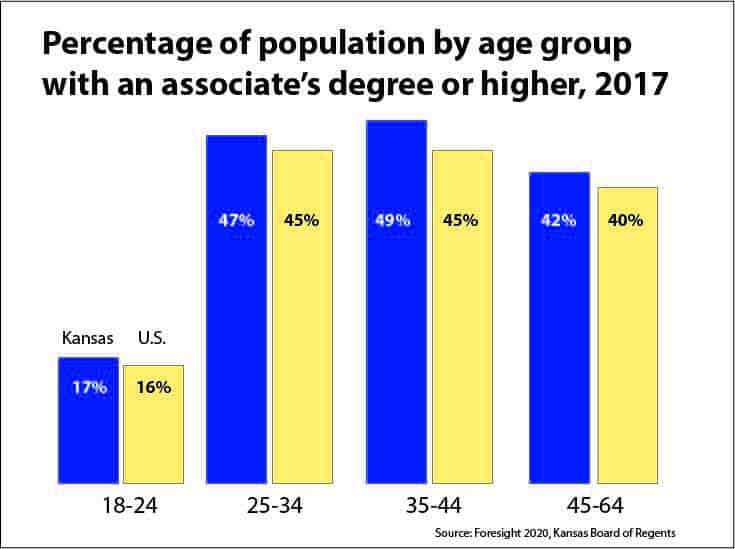

I’ve written before about the shrinking pool of traditional students in coming years amid changing social norms. Full-time undergraduate enrollment nationwide peaked in 2010 and has been flat or declining since then. And as long as the economy remains stable, universities are likely to have trouble attracting older students. Since 2010, the number of Kansans between the ages of 25 and 64 who are taking classes at regents institutions has declined 20.4 percent. That decline is even steeper among those 35 and older.

Most certainly, the regents’ report highlights successes. For instance, the number of engineering graduates has already surpassed the regents’ goal for 2021. The regents president and chief executive, Blake Flanders, also writes that the state’s public colleges and universities have made transfer among institutions easier and that most bachelor’s degrees now require 120 hours of credit.

The primary goal of the strategic plan is to increase the number of post-secondary credentials among Kansans as a means to improve the state’s economy. This includes associate’s degrees and certificates in various technical fields. KU would have to increase its number of graduates 25% over the next two years to meet the regents’ goal. That’s a Sisyphean task, given recent trends.

KU has certainly made progress toward retaining students and helping them graduate. This has involved such things as transforming classes to make them student-centered, streamlining core classes, improving advising, making better use of data, adding freshman courses with fewer students, and adopting a host of other strategies.

The need for a clearer path for students

Disciplines within liberal arts and sciences have also worked at providing a clearer roadmap for students, often taking on some of the strategies of professional schools. Earlier this month, Paula Heron, a physics professor at the University of Washington, spoke to physics faculty at KU about the findings of a report called Phys21, which she helped write. That report urges physics departments to look more practically at the value of a physics degree.

Physics, like so many disciplines, is set up primarily to move students toward graduate school and academic careers, Heron said. Most students, though, don’t want to stay in academia. Forty percent of physics students go directly into the workforce and 61% work in the private sector, she said. Among physics Ph.D.s, only 35% work in academia.

Heron urged faculty to “educate people in physics so they have a broader sense of the world.” Help students apply their skills to practical problems. Give them more practice in writing, speaking, researching, and working in teams. Help students and career counselors understand what physics graduates can do.

One of the biggest challenges is that most physics professors lack an understanding of the job market for their graduates. They have worked in academia most of their lives and don’t have connections to business and industry, making it hard for them to advise students on careers or to help them apply skills in ways that will prepare them for jobs.

The challenge in physics mirrors that of many other disciplines. Academic work tends to focus our attention deeper inside academia even as demographic, social and cultural trends require us to look outward. If we are to thrive in the future, we must shift our perceptions of what higher education is and can be. That means transforming courses in student-centered ways and rewarding research and creative work that informs our teaching and brings new ideas and new connections to the classroom. That doesn’t mean we must throw out everything and start over. Not at all. We must be flexible and open-minded about teaching and research, though. Ernest Boyer made a similar plea in 1990 in Scholarship Reconsidered, writing:

“Research and publication have become the primary means by which most professors achieve academic status, and yet many academics are, in fact, drawn to the profession precisely because of their love for teaching or for service – even for making the world a better place. Yet these professional obligations do not get the recognition they deserve, and what we have, on many campuses, is a climate that restricts creativity rather than sustains it.”

Much has changed in the nearly 30 years since Boyer’s seminal work. Unfortunately, universities continue to diminish the value of teaching and service and creativity even as their future depends on creative solutions to attracting and teaching undergraduates. We have ample evidence about what helps students learn, what helps them remain in college, and what helps them move toward graduation. What we lack is an institutional will to reward those who take on those tasks. Until we do, we will simply be pushing the enrollment boulder up a hill again and again.

More from the report

A few other things from the regents report stand out:

- Only Fort Hays State met the regents’ goal for the number of graduates and certificate recipients in 2018, and it actually exceeded that goal by 3 percent. KU fell short by 14.3 percent, and K-State fell short by 10.7 percent. Community colleges and technical colleges were 11.9 percent short of the 2018 goal.

- A third of students attending regents institutions received Pell Grants in the 2017-18 academic year, slightly above the national average. Between 2014 and 2018, though, the number of students receiving Pell grants declined by 7 percent at Kansas’ public universities.

- Pell grants, which in 1998-99 covered 92 percent of the tuition for a student at a public university, now cover only 60 percent.

- The number of Hispanic students continues to grow, with Hispanics now accounting for 11.1% of students at regents institutions, compared with 7.6% in 2010. Enrollment among blacks has been steady at 7.4% of the student population. That is up from 6.3% in 2010 but down from 8.1% in 2013.

- Another metric the regents created, a Student Success Index, seems cause for concern. That index accounts for such things as retention and graduation rates among students who transferred to other institutions. Among all categories – state universities, municipal university, community colleges and technical colleges – students performed worse in 2017 than they did in 2010.

Does the U.S. have too many college graduates?

Here’s a view that runs counter to the Kansas regents’ argument that public universities need to increase the number of graduates. It comes from Richard Vedder, an emeritus professor at Ohio University, who argues in a Forbes article and a forthcoming book that universities are producing too many graduates. His claim: “We are over-invested in higher education.”

Vedder argues that colleges and universities face a triple crisis: The cost of college is too high; students are spending less and less time on academic work; and there is a disconnect between what universities teach and what employers want.

I agree with all of those things, though I disagree with the idea that we have too many college graduates. Vedder seems to approach education in strictly utilitarian terms, with graduates fitting like cogs in the machinery of capitalism. If all universities did was match course offerings to job requirements, they would deprive students of the broader skills they need to carve out meaningful careers and the broader ability to make innovative connections among seemingly disparate areas. They would also deprive the nation of citizens who can dissect complex problems and cut through the obfuscation that permeates our political system.

Briefly …

Enrollment challenges are hardly limited to the U.S. In the U.K., regulators say universities are overestimating the number of international students they expect to attract in the coming years, The Guardian reports. That is significant because the traditional-age student population is expected to decline in coming years in the U.K., and universities are looking overseas to attract students. … Research done by makers of educational products often greatly overestimates the effectiveness of those products, a Johns Hopkins University study warns. Product makers often create their own measurement standards, exclude students who fail to complete a protocol, or dismiss failures as “pilot studies,” according to The Hechinger Report. That leads to inflated results that the study calls the “developer effect.” In many cases, companies obscure the funding source of their studies.