By Doug Ward

Monday’s solar eclipse provided many great opportunities for teaching and learning. Here are a few examples from a viewing event at the Shenk Sports Complex at 23rd and Iowa streets. The event was organized by the Department of Physics and Astronomy, with assistance from the Spencer Museum of Art, the Museum of Natural History, and the Lawrence Public Library.

Perhaps 2,000 people gathered at the Shenk playing fields to watch the eclipse. Layers of gray clouds blocked the view, but the crowd seemed to take things in stride. That may be the first lesson: Disappointing weather doesn’t always spoil the occasion.

Why we should care

Chris Fischer, an associate professor of physics and astronomy, dressed for the occasion. He was decked out in a conical hat and a T-shirt that bore a picture of the abolitionist John Brown (in sunglasses, of course) and this inscription:

99.3% Eclipse

Lawrence 2017

*totality not included

He and his colleague Gregory Rudnick, an associate professor of physics and astronomy, designed the shirt, which members of the KU physics and astronomy club sold at the eclipse event.

Fischer carried a wooden staff adorned with blue LED bulbs in one hand and a bullhorn in the other. The bullhorn was intended to help him point out interesting aspects of the eclipse. It mostly remained silent, though.

I asked Fischer what the takeaway was for a gathering like this. He pointed out the cultural significance of the eclipse, which most people will not see again in their lifetime. Scientifically, he said, the eclipse highlighted our understanding of such things as planetary physics, optics and scientific method.

“Isn’t it kind of impressive that we can predict when these things are going to occur?” Fischer said. “I’d like people to think that it’s pretty neat that scientists can make these predictions and they’re true. That’s how science is supposed to work.”

Art meets science (and the chancellor)

In a tent at the edge of the Shenk Sports Complex, staff members from the Spencer Museum of Art encouraged people to visualize the eclipse in an artistic way.

Celka Straughn, director of academic programs at the Spencer, said staff members had displayed historical and artistic examples of the corona of the sun at eclipse. Those images provided inspiration as steady streams of people gathered at tables inside the tent, using chalk and black paper to create their own representations of the corona. Once people had completed their drawings, staff members from the museum stamped the paper with “KU Eclipse 2017.”

Chancellor Doug Girod was among those who created eclipse artwork. Sporting a John Brown eclipse T-shirt over a long-sleeved dress shirt and a tie, Girod used a cardboard cutout to trace a circle and then drew chalk lines to represent the corona. He then posed with his drawing as museum staff members took his picture.

What happens to all those glasses?

Eclipse glasses were in short supply in many places around the country as the time of totality neared.

There were plenty to be found at the Shenk Sports Complex, though, as staff members from the Museum of Natural History distributed them from a tent at the edge of the playing field. By shortly after noon, the museum had distributed about 1,200 pairs of the cardboard glasses. People kept picking them up until the peak of the eclipse.

Many will no doubt keep the glasses as a memento of the eclipse. Many others, though, tossed the glasses into a large can the museum set out near its tent. It also had a large box of glasses that were never distributed. All of those glasses will go to good use, though.

Eleanor Gardner, outreach and engagement coordinator at the Natural History Museum, said the glasses would be shipped around the world to places that will have a solar eclipse in the coming years but might not be able to afford glasses to distribute.

Those who held on to the glasses can use them again in 2024, when the next eclipse will pass over the U.S. For that, Kansans will have to travel to Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas or Missouri (or places farther north and east). The next eclipse visible in Kansas will be in 2045.

Totality enters the vernacular

The word “totality” isn’t exactly obscure, but after Monday’s solar eclipse, it has become an everyday word.

It was printed on T-shirts, hats, mugs, buttons and posters. It appeared in headlines. TV anchors spoke about it. Google searches for “totality” surged over the previous week. Those who couldn’t make their way along the moon’s path tweeted about having “totality envy.” Meriam Webster listed “totality” in the top 1 percent of words that people have looked up recently.

As eclipse day approached, totality became a goal, an event, a quest. People flocked to the line of totality, a narrow path across country where the moon completely blocked the sun. That was in places like Leavenworth, Atchison, Hiawatha, St. Joseph, Mo., or North Kansas City. Lawrence reached 99.3 percent totality.

The percentage doesn’t really matter. “Totality” has become a cultural touchstone.

What would Shakespeare say?

In King Lear, Shakespeare wrote: “These late eclipses in the sun and moon portend no good to us.”

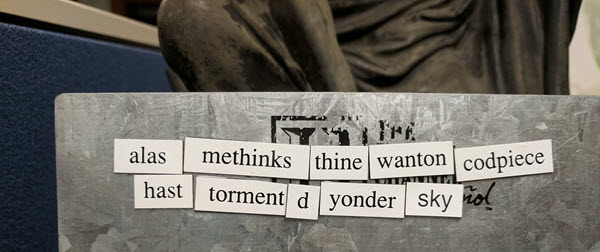

Over the weekend, I found a box of Shakespearean poetry magnets at a garage sale and created my own version of what Shakespeare might have said about the eclipse of 2017. You’ll find it below in totality.

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.